Dianne Payne led the HLF-funded project, Bushey during the Great War: a Village Remembers. She recounts here the story of Bushey’s artistic colony, which was closely associated with the Bavarian painter Hubert Herkomer. How did its members, women and men, respond to a conflict that fractured their previous ways of life? What longer-term effects did war have for memories of Bushey’s flourishing pre-war culture?

Bushey’s German Connection

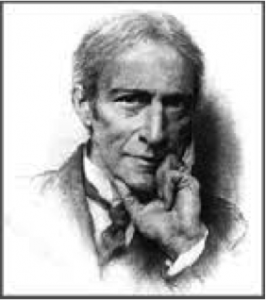

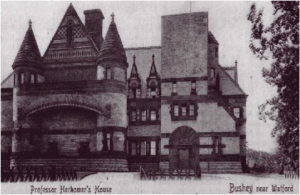

The village of Bushey in south-west Hertfordshire has a unique history with a strong German connection. Hubert Herkomer, born in 1849 in the Kingdom of Bavaria, a German state until 1918, settled in Bushey in 1873. By then he was established in London as an illustrator and water-colour artist. Herkomer had a wide range of artistic talents and ten years later founded an Art School in Bushey, which flourished for over twenty years, gaining an international reputation and transforming the village into a tiny university town. The crowning glory of the mini-campus, Herkomer’s extravagant house, Lululaund, was built in the style of a Bavarian castle and dominated the village.

Herkomer was appointed Slade Professor of Art at Oxford University as a successor to John Ruskin and by 1908 was titled Sir Hubert von Herkomer with honours from both Britain and Germany. Travelling back and forth between Britain and his homeland in the decade before the First World War to paint portraits of royalty, celebrities and businessmen from both countries, he used to say, ‘My art is English; my blood is German.’

Herkomer’s Art School closed in 1904 but the artistic colony he inspired continued to grow. By 1913 more than 70 artists were living in Bushey, including at least 36 of his former students, those from the Lucy Kemp-Welch School of Drawing and Painting in the village, and others who had chosen to live in an artistic community close to the capital. Herkomer, now retired but absorbed in a multitude of artistic activities, was naively unaware of the strength of gathering hostilities in Europe. In 1913 he accepted a commission to paint a group portrait of the managers and directors of the Krupp Company, the huge German arms-manufacturing empire run by one of Europe’s richest, most powerful families. The 19 Krupp directors travelled to Herkomer’s studio in Bushey to be painted from life – a steady stream of them for nearly a year.

The Managers and Directors of the Firm Fried. Krupp, Essen, Germany – Herkomer (1913)

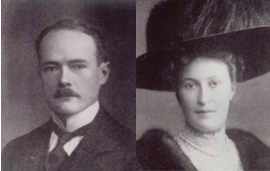

When Herkomer died in March 1914, Gustav Krupp von Bolen and his wife, Bertha, were among the mourners at his funeral in Bushey, no doubt using their visit to observe and report back on Britain’s readiness for war. A few months later the Krupp Company armed the forces of the Kaiser.

Gustav Krupp von Bolen and his wife, Bertha

Herkomer’s death, five months before war was declared against his beloved German homeland, was a merciful release, saving him from conflicting loyalties, the rending of friendships and loss of possessions that the war would have brought. His wife and daughter left for Germany a month before the war began and Lululaund stood empty, symbolizing the end of an era in Bushey village.

Herkomer ‘though English in nurture and sympathy, was German in blood and ancestral tradition’ so how did the artistic community he inspired react when war was declared? John Saxon Mills, a personal friend, recalled his own mixed feelings when in 1914 he saw the Krupp group portrait displayed in the gallery at the Royal Academy and reflected that Krupp’s guns were at that very moment killing British soldiers not many miles away. Herkomer had been loved and respected by his students and by the villagers but now, with Germany as the enemy, war brought a change of tone and purpose.

Swept along with patriotic enthusiasm, 28 Bushey men volunteered for war service immediately and by September that number had increased to 150. Nationwide, anti-German sentiment had been rife before the war but when the Kaiser’s army invaded Belgium, attitudes to Germany hardened and a wave of hysteria swept Britain. Anyone with German connections was regarded with fear and distrust and in New Bushey (Oxhey), Antonie Fackler, the licensed victualler of The Villiers Arms who had German nationality, was interned and lost all his possessions. Many changed or anglicized their German names to avoid victimization and Daniel Wehrschmidt, Herkomer’s principal tutor at the Art School, had altered his family’s name to Veresmith. Two of his sons and Gustav Koenigsfeld, who served under the name of Kaye, enlisted in British regiments and were among Bushey’s fatalities.

The early months of the war made little impact on the life-style or perceptions of some of the artistic community, who carried on with life as it was before. Miss Gray recorded in her diary how she went with friends by bus and painted on the bridge in Cassiobury Park in Watford, where a dozen young officers were being taught military tactics and how to assemble guns. ‘They charged us. It was lovely’, she naively commented. In 1915 the names of two female Bushey artists appeared in the Visitors’ Book at Seatoller House, a small guest house in the Lake District, where they were taking a holiday. But the sinking of RMS Lusitania in May that year and news that Lilian Clay, a former Herkomer student, had been a passenger and had drowned brought the conflict closer to home.

The arrival of Belgian refugees in Bushey in 1915 galvanized the local community into action. Miss Gray was among those who joined in activities on the Home Front and their arrival inspired Amy Brooke, a Bushey resident, to write words and music for two songs. One was entitled ‘Gallant Belgium’, and the other encouraged young men to join up. The stirring words and catchy tunes were sung with great success up and down the country. Herkomer and Bushey’s German connection were no longer relevant.

Anti-German prejudice and paranoia continued and in June 1915 two students from the Lucy Kemp-Welch Art School in Bushey were taken to Watford Police Station accused of spying, after being found innocently painting near Watford Bridge. Lucy Kemp-Welch was one of Herkomer’s most talented students, a fact that could have prompted their arrest. At any rate, her Art School was forced to close for the duration of the war.

The First World War stimulated the evolution of the propaganda poster, the ‘weapon on the wall’, persuasive ammunition in the battle for minds. In 1915 Lucy Kemp-Welch was asked to create a recruitment poster, encouraging men to enlist against Germany, the homeland of her former tutor. The model for the cavalryman was Rowland Wheelwright, another former Herkomer student, and the horse was Black Prince, belonging to General Baden-Powell, who had lent Lucy the horse in 1906 as a model for her painting.

The First World War stimulated the evolution of the propaganda poster, the ‘weapon on the wall’, persuasive ammunition in the battle for minds. In 1915 Lucy Kemp-Welch was asked to create a recruitment poster, encouraging men to enlist against Germany, the homeland of her former tutor. The model for the cavalryman was Rowland Wheelwright, another former Herkomer student, and the horse was Black Prince, belonging to General Baden-Powell, who had lent Lucy the horse in 1906 as a model for her painting.

The same year, in response to the bombardment of four North Sea ports by the German First High Seas Fleet, resulting in 137 deaths and 592 wounded, almost all civilians, Lucy’s sister, Edith, created the propaganda poster, ‘Remember Scarborough’. It reminded people why they had to fight back and encouraged them to enlist in the services or join the thousands of munitions workers on the Home Front.

The same year, in response to the bombardment of four North Sea ports by the German First High Seas Fleet, resulting in 137 deaths and 592 wounded, almost all civilians, Lucy’s sister, Edith, created the propaganda poster, ‘Remember Scarborough’. It reminded people why they had to fight back and encouraged them to enlist in the services or join the thousands of munitions workers on the Home Front.

As the war progressed and fatalities mounted, the reality of war against Germany hit home. 370 men from Bushey and Oxhey, including five former Herkomer students, died in theatres of war across the globe and many more returned home, their lives changed for ever.

In 1917 Herkomer’s extravagant mansion was used to billet 100 members of Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corp. The Bavarian castle, of which he has been so proud, had a relatively short life. In 1937, just before the Second World War, it was offered as a gift to the Bushey and District Council for use as a museum and art gallery. The building would have been difficult and costly to adapt but there is also little doubt that renewed anti-German feeling played a significant part in the councillors’ refusal. The following year it was largely demolished and much of the grand carving inside was burnt. All that remains today is the porch and entrance hall.

Herkomer, who had been the inspiration of the Art School in Bushey, became a victim of ongoing Anglo-German tension and his reputation as an artist was damaged by the antipathy to everything Victorian in the wake of the First World War.

Images courtesy of Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Sources

John Saxon-Mills, Life and Letters of Sir Hubert Herkomer: A Study in Struggle and Success (1923)

Lee MacCormick Edwards, Herkomer: A Victorian Artist (1999)

1911 Census (Ancestry.com) and Peacock’s Watford Directory, 1915

The West Herts and Watford Observer, 1914 & 15

Miss Gray’s Diary (Bushey Museum)

Visitors’ Book for 1915, ‘Seatoller House’, Borrowdale, near Keswick

Brooke, Agnes Amy, Two Songs: ‘Gallant Belgium’ and ‘Now step along you khaki boys’ (pub Novello & Co 1915) BL Music Collections H.1860 (28)