Contributed by Dr Helen Boak

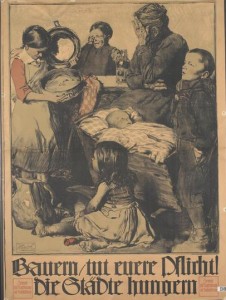

“Farmers – Do your Duty – The Cities are Hungry”

©Art.IWM PST 11290 http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/13556

In August 1916 a group of soldiers’ wives wrote to the Hamburg Senate demanding its support for a peace settlement: ‘we want to have our husbands and sons back from the war and we don’t want to starve any more’.1 The government’s failure to ensure adequate food supplies and their equitable distribution, particularly to poorer people living in Germany’s towns and cities, impacted upon popular opinion towards the government and also the population’s support for the war.

The German government had made no economic plans for a long war. In 1914 Germany depended on imports for about a third of her foodstuffs, fodder and fertiliser, and these were affected by, among other things, the blockade put in place by the British navy from November 1914. Germany became, to a large extent, dependent on what her own farmers could produce. German agriculture was a mix of large estates in Northern Germany and some four million small farms elsewhere. As men and horses were called up, farmers’ wives took over the running of the farm, but lack of equipment, fertiliser and manpower, even though some 900,000 prisoners of war worked on the land, saw substantial falls in crop yields, which almost halved by the war’s end. A lack of fodder led to livestock losing weight, impacting on the supply of meat and milk. In July 1918 meat rations amounted to 12% of pre-war consumption.2

The government, claiming that Germany had enough food to survive the blockade provided people reduced consumption, had to try and lower consumption and, at the same time, ensure that there was an equitable distribution of food at affordable prices at a time when priority was given to providing food for the army. Food provisioning on the home front was the responsibility of the local authorities. Across Germany individual towns and cities had traditional food supply chains, with some securing their provisions from the surrounding district and others, such as the Ruhr, dependent on supplies from further afield in Germany and abroad. This was to be significant as food shortages grew and transportation was affected by military demands, and, in the winter of 1916/17, by the weather.

At the start of the war there was a rush to buy staple foods to hoard, leading to price rises, and so the government allowed local authorities to introduce a system of price ceilings, which varied from place to place, not just in the maximum prices set but also the foodstuffs affected. Farmers, who resented interference in the free market, took their produce to places with higher or no price ceilings, or used it for animal fodder. This led in early 1915 to the slaughter of about one-third of Germany’s pigs, seen as competitors for scarce food resources, impacting on later meat and fertiliser supplies. From October 1914 to eke out grain supplies bakers were allowed to use potato flour in the making of bread, the so-called K-Brot (K for Kartoffeln (potatoes) or, more patriotically, Krieg (war)), but continuing shortages led to the rationing of bread from January 1915. Throughout the war, other additives such as corn, lentils and even sawdust were used to eke out bread.

The autumn of 1915 was to see food riots in several German cities, as women protested about the new higher price ceiling for butter and food shortages.The government responded by decreeing that no fats were to be sold on Mondays and Thursdays, no meat on Tuesdays and Fridays and no flour at week-ends. A wave of food-related riots spread across Germany in summer 1916 and women would march to the town hall and demand better food supplies. Potatoes had been rationed in April 1916, butter and sugar in May, meat in June and eggs, milk and other fats in November. In late 1916 the government decreed that workers in heavy industry could receive extra rations. Women in the last three months of pregnancy also got extra rations, including full milk, to which children under six were also entitled. The amount of rations varied from place to place, which caused unrest as some areas felt others were receiving more. Women would begin to queue for their rations early, often bringing their folding chairs and their knitting, to ensure they got something. If the shop sold out, they had to go and queue elsewhere. However, rations were not always available. Toni Sender, a pacifist feminist, later wrote ‘more often than not the word “butter” on the ticket was all one saw of butter’.3 In the winter of 1916/17 weeks went by without potatoes, because of the poor harvest and transportation difficulties, and the turnip was used extensively as a replacement – it, too, was rationed. The Head of the Prussian Commission for the Provisioning of the People noted, ‘women’s wallets were filled with food ration cards of every kind, but the rations were often so minimal that it wasn’t even worth picking them up’.4 In January 1917 Princess Blücher, an Englishwoman married to a Prussian aristocrat, wrote in her diary: ‘we are all growing thinner every day, and the rounded contours of the German nation have become a legend of the past. We are all gaunt and bony now, and have dark shadows round our eyes, and our thoughts are chiefly taken up with wondering what our next meal will be’.5 By summer 1917, rations amounted to some 1,000 calories daily, about 40% of pre-war intake, but fluctuations in the harvest saw the calorific value of rations increase to 1,400 by summer 1918.6 During the war over 11,000 substitute foodstuffs were approved and they were of dubious nutritional value. Princess Blücher noted in her diary that ‘I don’t believe that Germany will ever be starved out, but she will be poisoned out first with these substitutes’.7

Food shortages were felt most acutely in urban areas, and affected the poor disproportionately as they were dependent on rations and could not afford to buy food on the black market. By 1918 an estimated one third of Germany’s food supplies were being sold on the black market, and one of its biggest customers was heavy industry which bought in supplies to boost its workers’ rations. Ethel Cooper, an Australian musician who spent the war in Leipzig, could afford to eat in restaurants and throughout the war received food and hospitality from an English friend married to a German wool merchant who got food from their estate in the countryside. Ethel noted that she could eat pheasant and pigeon, but had no sugar, flour or milk.8

Food was more readily available in the countryside, and urban consumers came to believe that rural producers were profitting from their suffering. If the urban poor had relatives in the countryside they could obtain food from them, or they could ‘hamster’ – travel into the countryside and barter, buy or steal from rural producers, though they ran the risk of having the food confiscated by inspectors at railway stations on their return. On one day in June 1917 inspectors at a small West German town confiscated ’36 pounds of butter, 421 eggs, 5 hundredweight of flour, nearly 30 pounds of peas, 42 pounds of veal and 12 pounds of ham’.9 But the authorities were complicit – the railways put on extra trains to cater for the hamsterers, who were aggrieved that black marketeers and war profiteers could go about their business with impunity.

Children of Berlin being fed with midday soup from a mobile field kitchen. Taken during the First World War by an official German government photographer.

©IWM Q 88186

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205331722

In 1916, with food prices having doubled since the start of the war, the government ordered all towns with over 10,000 inhabitants to expand their provision of soup kitchens, to ensure that people had access to one warm meal a day. By October 1916 some 357 towns had 1,438 kitchens, by February 1917 472 towns had 2,207 soup kitchens.10 Use of the kitchens depended on the amount of foodstuffs available in the shops, and the spring of 1917, following the failure of the potato harvest in 1916 and the difficulties caused by the harsh winter in the transportation and storage of food, saw an increase in demand. In Hamburg, where the use of soup kitchens was high, some six million portions were served in April 1917 and over a year later some 20% of the population continued to eat a meal from a soup kitchen.11 From late 1916 customers had to exchange their weekly meat and potato ration cards in order to get a week’s ticket for a soup kitchen meal, and they also paid a small sum.

Those who could tried producing food for themselves – on balconies, keeping goats, rabbits and hens. Towns, too, turned parks into fruit and vegetable plots to feed the people. In Stuttgart authorities bought 740 acres of land to keep pigs fed by recycled kitchen waste. Once sold the money was used to feed 7,500 schoolchildren.12 But the opportunities for the urban poor to produce food for themselves were limited, and so they were reduced to hamstering, and, as the war went on, looting or stealing. The numbers of women convicted of crimes against property doubled between 1913 and 1917, and there was a growth in youth crime, as they, too, stole.

From 1917 onwards a deterioration in the health of the nation was clearly visible, with increases in stomach and intestinal illnesses. The Germans estimated that some 763,000 people died during the war from malnutrition and its effects. Between 1913 and 1918 the death rate from tuberculosis in towns with more than 15,000 inhabitants rose 91.1%. The numbers dying of typhoid doubled between 1916 and 1917.13 In Düsseldorf the number of reported cases of dysentry rose from 8 in 1914 to 351 in 1917.14 By December 1918 over half the children in Chemnitz’s schools suffered from anaemia, children across Germany were smaller and lighter, and 40% of them suffered from rickets.15

The armistice in November 1918 did not bring much easing in the food crisis. It was to be July 1919 before the blockade was lifted and disturbances over food continued throughout 1919. Some price controls and rationing of various foodstuffs remained in place until 1922. In June 1921 a million children a day were fed in the 2,271 food kitchens run by the Quakers in 1,640 German communities.16 The Nazis were to learn the lessons of the government’s inadequacies in maintaining adequate food supplies on the home front during the First World War and tried to ensure that racially valuable Germans had sufficient to eat during the Second World War.

Plant oil! Plant sunflowers and poppies, thus producing German oil and serving the fatherland! Seeds and instructions from the War Committee for Oils and Fats, Berlin W.8.

©Art.IWM PST 3234

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/10896

References

1 Quoted in Ute Daniel, ‘Der Krieg der Frauen 1914-1918: Zur Innenansicht des Ersten Weltkriegs in Deutschland’, in Gerhard Hirschfeld, Gerd Krumeich, Irina Renz (eds), ‘Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch…’. Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkriegs (Essen: 1993), p. 131.

2 David Welch, Germany and Propaganda in World War I. Pacifism, Mobilization and Total War (London, 2000), p.128.

3 Toni Sender, The Autobiography of a German Rebel (London, 1940), p.81.

4 Quoted in Belinda Davis, Home Fires Burning. Food, Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin (Chapel Hill, 2000), p. 197.

5 Evelyn, Princess Blücher, An English Wife in Berlin (New York, 1920), p. 158.

6 Welch, Germany and Propaganda in World War I, p. 165; Roger Chickering, Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914-1918 (Cambridge 3rd ed., 2014), p. 165.

7 Blücher, An English Wife in Berlin, p. 122.

8 Decie Denholm (ed.), Behind the Lines. One Woman’s War 1914-1918 (London, 1982), p. 165, letter of 5 November 1916.

9 Ute Daniel, ‘The Politics of Rationing versus the Politics of Subsistence: Working-Class Women in Germany, 1914-1918’, in Roger Fletcher (ed.), Bernstein to Brandt. A Short History of German Social Democracy (London, 1987), p. 92.

10 Christoph Regulski, Klippfisch und Steckrüben. Die Lebensmittelversorgung der Einwohner Franfurt am Mains im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918 (Frankfurt am Main, 2012), p. 179.

11 Chickering, Imperial Germany and the Great War, p. 166; Keith Allen, ‘Food and the German Home Front: Evidence from Berlin’, in Gail Braybon (ed.), Evidence, History, and the Great War: Historians and the Impact of 1914-1918 (Oxford, 2003), p. 178.)

12 Keith Allen, ‘Sharing Scarcity: Bread Rationing and the First World War in Berlin, 1914-1923’, Journal of Social History, 32:2 (1998), pp.371-93, here p. 377.

13 Regulski, Klippfisch und Steckrüben, pp. 319-20.

14 Elizabeth Tobin, ‘War and the Working Class: The Case of Düsseldorf 1914-1918’, Central European History, 13:3/4 (1985), pp. 257-98, here p. 292.

15 Chickering, Imperial Germany and the Great War, p. 144.

16 http://www.quakersintheworld.org/quakers-in-action/302, accessed 13 March 2015.

Useful Further Reading

Roger Chickering, Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914-1918 (Cambridge 3rd ed., 2014)

Ute Daniel, The War from Within: German Working-Class Women in the First World War, trans. Margaret Ries (Oxford, 1997)

Belinda Davis, Home Fires Burning. Food, Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin (Chapel Hill, 2000)

Gerald D. Feldman, Army, Industry and Labor in German 1914-1918 (Providence, 1992)

Elizabeth Tobin, ‘War and the Working Class: The Case of Düsseldorf 1914-1918’, Central European History, 13:3/4 (1985), pp. 257-98.

David Welch, Germany and Propaganda in World War I. Pacifism, Mobilization and Total War (London, 2000)

Benjamin Ziemann, War Experiences in Rural Germany, 1914-1923 (Oxford, 2007)

Ida Zweiniger-Bargielowski, Rachel Duffett, Alain Drouard (eds), Food and War in Twentieth Century Europe (Farnham, 2011). Chapters by Hans-Jürgen Teuteberg and Peter Lummel