John H. Taylor has recently completed a research project into the experiences of Conscientious Objectors and those who supported them in the area of London covered by the current London borough of Southwark. In this article he gives an introduction to the sources, people and issues which he uncovered. John has very generously provided a pdf of his research which can be accessed by following this link.

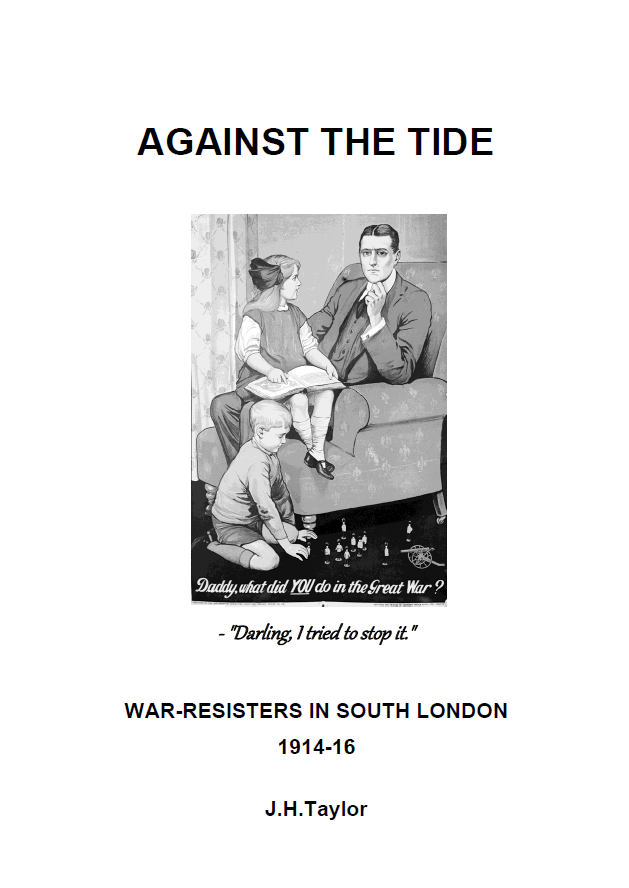

Against the Tide: War-resisters in south London 1914-16 by J. H. Taylor

Just self-published, my research focuses on those who stood out against the war in the present London borough of Southwark. Here there were two centres of opposition. One was in Bermondsey in the north, around the Christian socialists Alfred and Ada Salter, who were both active at national level. Their part is well documented. Dulwich, the second and rather surprising centre in the south, is barely known at all.

Here an active branch of the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), covered not only Camberwell and Peckham but took in and looked after conscientious objectors from Lewisham and Deptford. Something of its activity and of its leading actors has now been recovered, using among other sources the Catherine Marshall archive in Carlisle (http://www.cumbria.gov.uk/archives/archivecentres/cac.asp ) and the archive of Arthur Creech Jones in the Bodleian, at Oxford (http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/bodley )

The first of these includes material that gives a lively picture of the relations between the branch (and branches generally) and the ever-demanding Miss Marshall. She, as readers will know, was the NCF’s remarkable driving force: as organiser, campaigner, and lobbyist.

Creech Jones was a studious civil service clerk and ILP man who helped form the Dulwich branch. Court-martialled and jailed in September 1916, he served four terms of hard labour, only emerging from prison in April 1919. His correspondence with his family survives, as do letters from his cousin Violet, who later gives a lively account of the campaigning outside.

My research also makes extensive use of the three local newspapers. It does so, in the first place, in order to examine the operations of the three Military Service Tribunals (Southwark, Bermondsey and Camberwell). Bertrand Russell referred to the tribunals’ treatment of conscientious objectors as a “madness of persecution.”

That’s not what I found. As reported, tribunal members don’t on the whole appear to bully or hector. Instead they attempt to test the genuineness of the convictions professed and where possible to show up their inconsistency and eccentricity. When in Camberwell there were derogatory remarks – “We don’t want to hear all their trash” – other tribunal members spoke out to rebuke their colleagues and urge that all applicants be treated with courtesy.

The reports also reveal other tensions. In Southwark there were repeated “breezes” between tribunal members and the Military Representative. They see themselves, with their local knowledge, as representing, in part at least, the needs of the community. He keeps appealing against their decisions on the basis that the men in question “ought to be serving the King.” They were more than just a compliant civilian cog in the military machine – though ultimately they are ground down as more and more men are demanded for the slaughter.

The sheer volume of non-conscientious applications for exemption is striking – Southwark was processing 400 cases a week in June 1916 – as is the complexity of multiple applications; from Bermondsey’s leather trade, for example, so vital for the army. One can’t help being impressed by the tribunals’ dedication to teasing these out.

I have sought to present my research in context: in the context of the war and national politics, in the context of national campaigns to end the fighting and in the context of the home front. I use the local press to illuminate the latter – by how they report the “drink crisis,” the air raids and the peace campaigners (for example) and by what their editorials say.

There are notable differences in the way the three papers report the war. Two of them play it down to rarely more than a single column of selected casualties. The South London Press, on the other hand, is saturated in the war, particularly from mid-1915 when “The War Week by Week” – across two columns top-left – replaces adverts on the front page and is supplemented, either there or inside, by a personalisation of the conflict in terms of local engagement, heroism and sacrifice. The Walworth Wheelers as fighting men, 2,311 men of the South Metropolitan Gas Company on active service, south London public schoolboys “meeting death cheerfully,” innumerable “families in khaki” portrayed in oval vignettes – and so on.

For me, hovering behind the high principle of the absolutists and the strenuous efforts at national level of the various anti-war campaigners are two questions. Firstly, how did civilian morale hold up in the face of repeated military failure and the never-ending lists of dead and wounded? Secondly, why after the disaster on the Somme did the pressure for a negotiated peace not prevail? Presumptuously perhaps, I attempt to provide some answers.

This volume takes the story up to the end of 1916. Against the Tide is or will be available in a range of libraries, including Southwark Local Studies, Friends’ House, the Peace Pledge Union, the Imperial War Museum, the British Library, and the First World War Centre at the University of Herts.

You can access a pdf copy of Against the Tide here