Contributed by Andrew Maunder

In its notice of her death in 1978 The Times explained of Berta Ruck (1878-1978) that she had been “a novelist of popular stamp, who wrote very largely for and about young girls” and who referred to literature as “the amusement business” (12 August 1978, p.14 ).

In its notice of her death in 1978 The Times explained of Berta Ruck (1878-1978) that she had been “a novelist of popular stamp, who wrote very largely for and about young girls” and who referred to literature as “the amusement business” (12 August 1978, p.14 ).

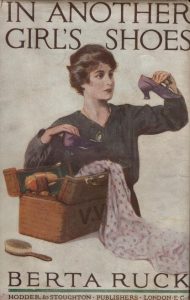

It was different in 1914 when most would have known who she was. Originally an illustrator, Ruck began writing in about 1905. Her ability to write quickly (the result, she claimed, of not planning anything) allowed her to take advantage of the expanding magazine market. She began with stories in middle-brow publications such as Home Notes and Home Chat – the latter running her serial His Official Fiancée. So popular was this story about a girl who marries her employer that Ruck expanded it into a novel and had her first hit. It set the tone for the stories of love and misunderstanding which followed for the next thirty years.

Ruck’s popularity increased in the years 1914-1919. She begins chapter twenty of her autobiography, A Storyteller Tells the Truth, with the observation that: “By the end of the War, I was more or less established in my modest niche as a writer for – and about – young girls” (p.146). Ruck did not change tack but she was always topical so her heroes and heroines invariably donned military or nursing uniforms as in The Lad With Wings (1915). Ruck’s work was escapist and frothy but determinedly optimistic about the power of love and the possibility of reunion after the fighting. It struck a chord with readers.

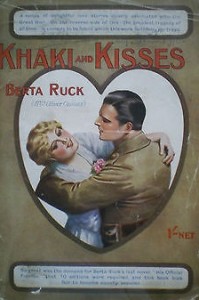

The topicality of Ruck’s war-time novels – Miss Millions Maid (1916), The Lad Has Wings (1916), The Girls at His Billet (1916), The Land Girl’s Love Story (1918), The Years for Rachel (1918) and Three of Hearts (1918) – is also evident in her short stories. These tend to possess a sharper edge. In October 1914, her tale of an English girl married to a German caused a stir when published in Pearson’s Magazine. This was followed in the same magazine by stories which would make up Khaki and Kisses (1915). The collection’s title captures its romantic mood but its stories (very much of their moment) are often outspoken about war-time hypocrisy. In “The Shirker” Ruck is scathing about pampered women who label men cowards while doing little themselves to help their country.

The topicality of Ruck’s war-time novels – Miss Millions Maid (1916), The Lad Has Wings (1916), The Girls at His Billet (1916), The Land Girl’s Love Story (1918), The Years for Rachel (1918) and Three of Hearts (1918) – is also evident in her short stories. These tend to possess a sharper edge. In October 1914, her tale of an English girl married to a German caused a stir when published in Pearson’s Magazine. This was followed in the same magazine by stories which would make up Khaki and Kisses (1915). The collection’s title captures its romantic mood but its stories (very much of their moment) are often outspoken about war-time hypocrisy. In “The Shirker” Ruck is scathing about pampered women who label men cowards while doing little themselves to help their country.

Despite writing over 100 books over a sixty-year period, when Ruck is mentioned nowadays it’s usually in connection with a spat between herself and her famous contemporary, Virginia Woolf.

In Jacob’s Room (1922) Woolf includes a description of a churchyard: “Yet even in this light the legends on the tombstones could be read, brief voices saying `I am Bertha Ruck, I am Tom Gage.’” The reference seems to be a dig at Ruck’s lack of relevance in the post-war literary world. But as Quentin Bell points out in his biography of Woolf, Ruck, who was “very much alive and inclined to be litigious on the subject of her literary extinction”, was furious and had her solicitor send a letter (II 91). The two women met (an event  described in comic terms in Woolf’s letters), patched things up and even went to the theatre together, Woolf maintaining all the while that she had used the name unconsciously.

described in comic terms in Woolf’s letters), patched things up and even went to the theatre together, Woolf maintaining all the while that she had used the name unconsciously.

Woolf’s claim not to have registered the name `Berta Ruck’ is hard to believe. Ruck may not have been a frequent visitor to the literary salons of Bloomsbury but hers name was to be reckoned with in the 1920s. It was as the Edinburgh Review noted in 1922 “on every bookstall”. Her novels – so popular with war-time readers – deserve revisiting.

Short Story:

Published: Khaki and Kisses (London: Hutchinson, 1915), pp.196-203.