Three members of the Women’s Land Army raise their hoes in salute

© IWM Q30678 IWM www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205124921

Contributed by Julie Moore

For this third in a series of occasional blogs on ‘anonymous’ women, I thought I would share with you one of those very exciting moments that can happen when doing research; the sort of moment when you look around the archive reading room or library, hoping to catch somebody’s eye and share with them the gem that you have found, and which makes the hours of wading through committee reports on drainage and road maintenance worthwhile.

Anybody who browses the website of the Imperial War Museum, looking for images of women involved in farming, will be greeted with a series of very appealing photographs of smiling, mainly young, women brandishing hoes, attacking hedges with gusto, or taking control of the dairy herd. The photo which heads this piece is fairly typical. A search of the IWM collection for ‘women’ and ‘farming’ will throw up 151 photographs from the First World War, and, other than a few showing rural women in France, the great majority of images depict young girls of the Women’s Land Army at work.[1] That these photographs exist is a reflection of the shortage of male labourers on farms, as well as the desire of the government to persuade not just the general public but also farmers of the valuable contribution these young women might make. It was not easy, and the girls had to work long and hard to prove themselves to their male employers and colleagues.

Quite rightly, a lot of work has been done on uncovering their stories,[2] but a recent article by historian Dr Nicola Verdon has flagged up the fact that just as important for the war effort was the work of what might be called ‘village women’.[3] These women were less glamourous than their WLA sisters and wore no smart uniform, but they were valued by farmers as they came from agricultural labouring families, needed no special housing and were more willing to be employed as and when needed.

Women, such as these, fall easily into our ‘anonymous women’ category; employed part-time and on a casual basis, they are less likely to appear in farming account books, which are themselves thin on the ground in the archives.

So, you can imagine my joy when I opened a folder of correspondence between a Hertfordshire farmer and the County’s War Agricultural Committee on the twin subjects of orders to plough up land to sow for wheat, and an application for exemption from military service for his son. In a letter to the Committee, he set out the evidence for why his son should be allowed to stay on the farm, and at the bottom of the letter he gave as evidence of his efforts on behalf of the war effort the following:

Extract from letter sent by F.J. Lukies of Shingle Hall, Sawbridgeworth applying to the Hertfordshire Agricultural Executive Committee for an exemption from military service for his son, Francis Nicholas Lukies. Courtesy of Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies AEC27/120

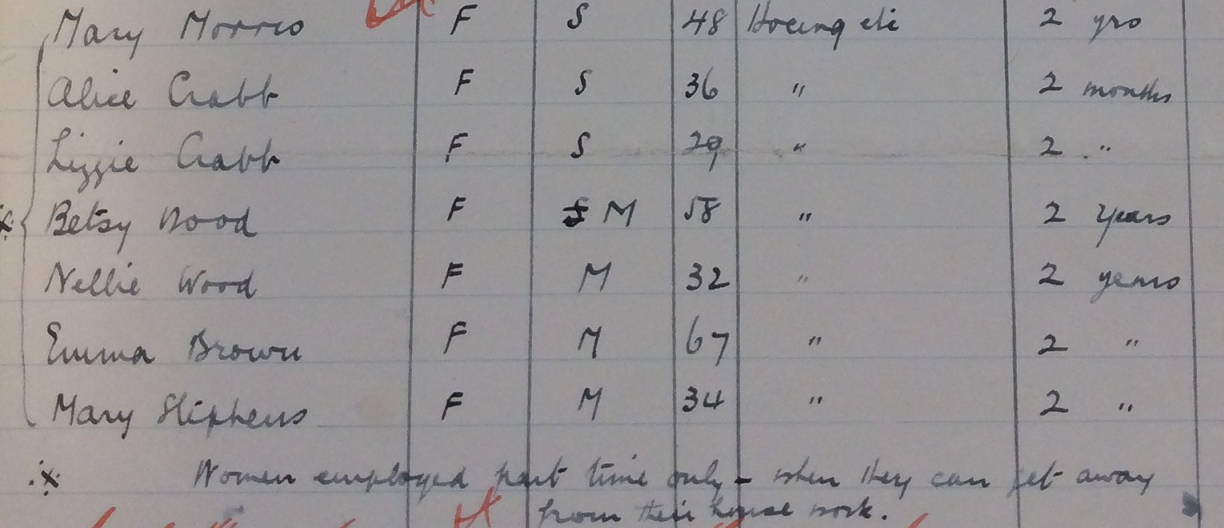

This, in itself, was interesting, as farmers were very often criticised for not employing more women on routine jobs. However, it got even better; John Lukies was clearly a man who was thorough in his preparations, for attached to the letter was a list of all those whom he employed on his 700-acre farm, and there, at the bottom of the list, were the names of those seven women with a note that they were ‘employed part-time only – when they can get away from their housework’. Here was my eureka moment, particularly welcome as I had not been expecting to find anything on women in a series of reports from 1917 on land suitable for ploughing. Somehow that makes the finding of a note such as this even more precious, although that does mean we have to avoid giving it rather more significance than it deserves

Extract from list of workers sent by F.J. Lukies of Shingle Hall, Sawbridgeworth to the Hertfordshire Agricultural Executive Committee as supporting evidence for exemption from military service for his son, Francis Nicholas Lukies. Courtesy of Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies AEC27/120

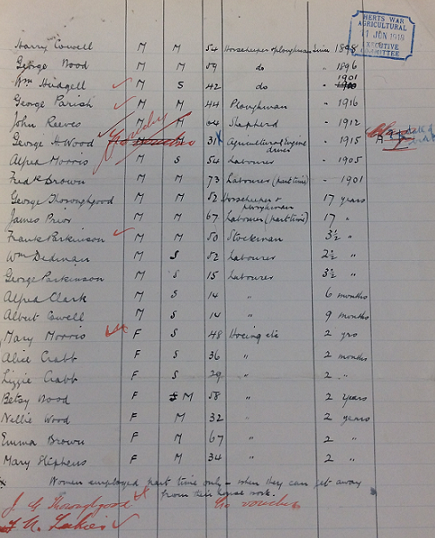

Now I had the names, but what to do with them? First thing was to check the census returns for 1911.[4] As ever with the census, this was not quite the put-name-in-get-result-out that would make life so easy. However, after about an hour of cross-checking with other census returns, I was able to find something for all seven women, which told me that they all came from labouring families and had all lived in the district for many years. Alice and Lizzie Crabb were sisters, whilst Betsy was mother-in-law to Nellie. I then took a look at the names of the men who appeared on the list (see below), and by going back to the census was able to confirm that four of the women had obvious family connections to men employed by Lukies.

Now you might be asking – so what? And, to be honest, beyond the satisfaction of making these links and putting these women into some sense of their geographical and familial space, I am not sure I can give an answer to this. There is also the point that the men who appear on the list are as entitled to be considered anonymous as their womenfolk. However, research has to start somewhere. I have the men on file now, so I can return to them if the work seems to be leading in that direction. In the meantime, their female colleagues fit the profile identified by Nicola Verdon of local families with farming connection: working on a casual basis but probably not identifying themselves as agricultural labourers. Rather, they are women who do a necessary job, such as hoeing, when required; but, when not, they are fully occupied elsewhere with work which is harder to quantify in economic terms but no less valued by their families and local communities for that.

I have my first women. It now remains to be seen whether they end up as my only women.

List of workers sent by F.J. Lukies of Shingle Hall, Sawbridgeworth to the Hertfordshire Agricultural Executive Committee as supporting evidence for exemption from military service for his son, Francis Nicholas Lukies. Source Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies AEC27/120

[1] Search made on 5th April 1917 www.iwm.org.uk, filters applied were First World War (subject period) and photographs (category)

[2] Bonnie White, The Women’s Land Army in the First World War, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), is the latest book to look in depth at the experiences of the WLA.

[3] Nicola Verdon, ‘Left out in the Cold: Village Women and Agricultural Labour in England and Wales during the First World War’, Twentieth Century British History, Vol. 27 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-25. This article is currently on open access here

[4] www.ancestry.co.uk and www.findmypast.co.uk are subscription services which offer access to the census as well as other genealogical records. Check with your local library or archive as many offer access free of charge.