by Kathleen McIlvenna, Institute of Historical Research

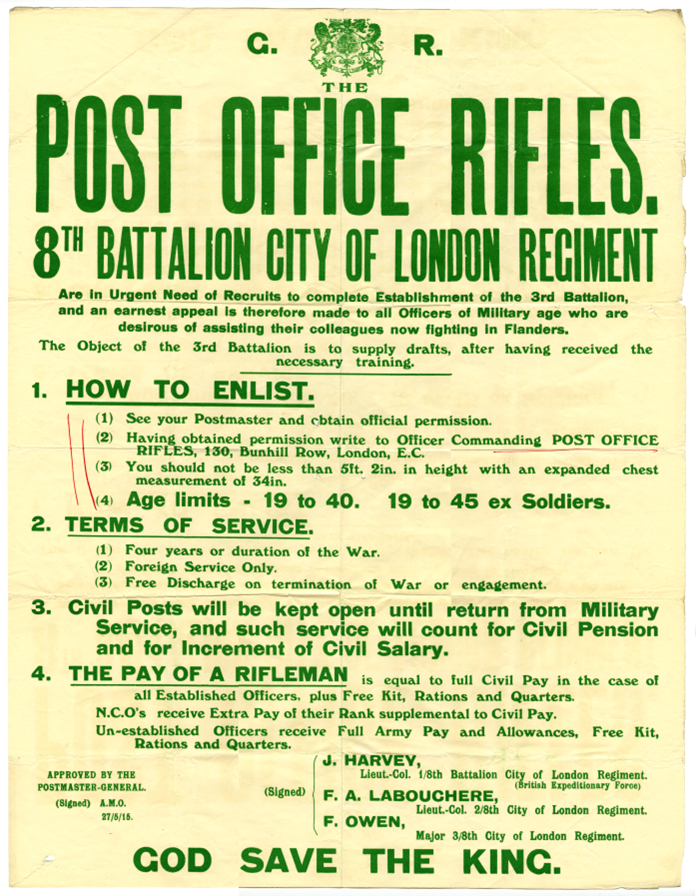

As the twentieth century dawned the Post Office took its place as an integral part of everyday life in Britain. Not only was the Post Office responsible for the delivery of letters but it was also the custodians of the telegraph, the Savings Bank and other areas of official administration. Furthermore the new century saw its responsibilities expand absorbing the new Old Age pensions from 1908 and the newly nationalised telephone network from 1912. With this enormous portfolio it is unsurprising that by the outbreak of the First World War the Post Office was the largest single employer in the United Kingdom, and this workforce had a major role to play in the Great War. The department’s official military unit, the Post Office Rifles, was quick to recruit and send men abroad. Many other workers joined their local units or took their postal work to war through the Army Post Office. It was thought that 20,000 men silently disappeared from the service in the first month alone.

Female Employees

As with many occupations women appeared to meet the growing shortfall in manpower. The Post Office had been employing women for several decades, but the war forced them to put women in more traditionally male roles and by November 1916 the Post Office employed over 35,000 temporary female workers.[1] For many women the Post Office was an attractive employer and could be less dangerous than the obvious alternatives. Elsa Thomas was trained as a sorter on the night shift in a Post Office near Leeds. Her oral history held by the Imperial War Museum presents a rose-tinted view of her work, focused on being given a stool to sit on and being allowed coffee breaks.[2] These may appear to be small privileges, but her enjoyment is particularly understandable in the context of the danger experienced in munitions work. Elsa was recruited from the Post Office to work in munitions and her oral history also describes the shock of arriving at Barnbow munitions factory in Leeds one the evening to discover 50 women had been killed in an explosion earlier that day.[3]

Dangers

The Post Office may have appeared as a safe haven, but it was not completely free from danger. In July 1917 a bomb was dropped on the Central Telegraph Office during a daylight raid in London. No one was injured as the floor had been cleared, but the whole service was brought to a halt for a few hours. This was extremely serious at this time of war, the War Office calls alone averaged 16,000 per day, and government telegrams had risen from 600,000 in 1913 to approximately 11 million between 1917 and 1918.[4] The skill and speed of the workers saw the Birmingham office transformed into the centre for the inland service by that afternoon, and remarkably normal service was resumed at the Central Telegraph Office within three days.[5]

These dangers were real, but for many workers they paled in comparison to what their colleagues were going through in the theatres of war. Edwin Purkiss was a postman in the South-Western District in London, he was over 50, so too old to fight, but in his reminiscences, preserved in the British Library, he describes his efforts to help the soldiers. Working and fundraising with colleagues a “Welcome Club” was established that welcomed back any Post Office staff returning from the colours, the club’s repertoire even included an orchestra to visit hospitals.[6] Edwin may not have gone to the Western Front, but he certainly felt he was ‘doing his bit’, and clearly had a network of men inside and outside the Post Office to support his efforts.

Conscientious Objectors

However, despite the fundraising and rallying of staff, Post Office employees were not all patriotic supporters of the war. Charles George Ammon was a sorter in the South-Eastern District Office, London, but he was also a grass roots activist and involved the trade union movements.[7] Charles Ammon left the Post Office in 1916, the reasons are unclear, but the following year he published the sermon ‘Conscientious Objectors and The Government’s Waste of National Resources’. This sermon condemns the imprisonment of conscientious objectors as ‘wasteful and stupid’.[8] The tract covers several occupations but the Post Office is singled out and condemned as ‘the one-time safety and regularity of the postal system has become a memory’.[9]

As a postal employee Charles had seen a dramatic reduction of the service. The number of deliveries across the country had been cut drastically, and Sunday deliveries were lost completely. Some offices had to close due to lack of staff and there were sharp increases in the number of complaints regarding lost post, as well as the number of staff dismissals due to dishonesty.

The Post Office clearly suffered under the strain of the war. Yet, its role at the heart of people’s lives handling matters very close to their hearts prohibited any major protest and ensured the longevity of this friendly face of government.

Find out more about the history of the Post Office and the First World War with BPMA podcasts. Click here.

__________________

[1] Post Office. Report of the Postmaster General on the Post Office. 1915-16, p.2

[2] Elsa Thomas interview, Reel 6, Imperial War Museum, http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80000672 (1 June 2014)

[3] Elsa Thomas interview, Reel 6, Imperial War Museum, http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80000672 (1 June 2014)

[4] Sir Evelyn Murray, The Post Office, (London, 1927) p.202, p.206

[5] Sir Evelyn Murray, The Post Office, (London, 1927) pp.206-207

[6] Edwin Purkiss, ‘Memories of a London Orphan Boy’ written in 1957. Held at the British Library, p.8

[7] Oxford Dictionary of National Biography http://0-www.oxforddnb.com.catalogue.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/view/article/47321 (1 June 2014)

[8] Charles Ammon, Conscientious Objectors and The Government’s Waste of National Resources, (London, 1917), p.7

[9] Charles Ammon, Conscientious Objectors and The Government’s Waste of National Resources, (London, 1917), p.7