Serious recognition was only given to Britain’s food crisis around September 1916, when an increasing number of ships carrying food supplies to Britain were sunk by German submarines. From 1913 Britain was importing around 81% of its wheat supplies with 36 million acres of British farmland devoted to livestock and only 3 million acres to crops such as grain and potatoes. From around this date, farmers produced all the nation’s milk and three-fifths of the meat, but only one-fifth of the bread, a staple foodstuff for the lower classes. Further adding to the country’s worries in the autumn of 1916 was the poor harvest worldwide, so that imports of grain ceased, and Britain only had sufficient stocks to last for 4 months normal consumption. The British potato crop, another staple item of diet, also became diseased and rotted in the ground due to the bad weather.

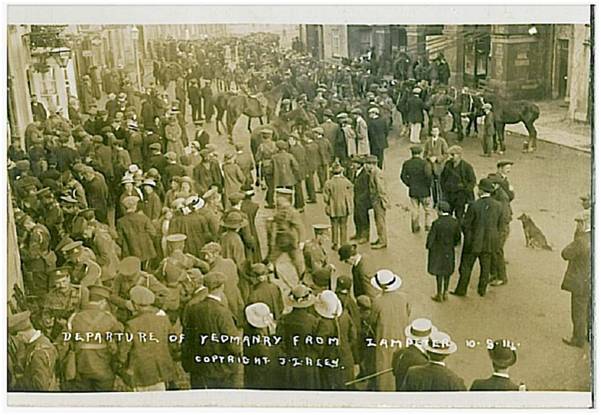

A manpower crisis had also developed in British agriculture. Up to December 1916 the focus under the Asquith government had been on the increasing need to recruit sufficient soldiers and sailors to fight the war, so that agriculture lost many of its fit young skilled labour. This loss of men from the land began to be recognised in autumn 1915 when protection was given to skilled farm workers who were given the status of indispensable civilian workers, not to be called up into the armed forces, although they could volunteer and would then be placed on a waiting list. However, by late 1916 with the army’s continuing need to recruit more men to fight, fit young farm workers were being specifically targeted by army recruitment officers at agricultural fairs with a significant number signing up.

In December 1916 with the escalating food crisis and severe worries by the nation that it could starve, the government under David Lloyd George took control of farming under the ‘plough policy’ to extend the arable acreage. The Minister of Agriculture, Rowland Prothero, told the County War Agricultural Committees that “the reason that we have not so much food at the present time is that we are not making the best use of the land” The plough policy enabled farms to be inspected to enforce cultivation orders and to take over farms which were seen as inefficient. The War Agricultural Committees were also to provide manpower, equipment and fertilisers.

Further government initiatives, under the Department of National Service, were to attempt to relocate labour to where it was most needed. In March 1917 an appeal to the Police Sergeant’s Conference and also to local councils for men with ploughing experience resulted in policemen from around Britain being released for the planting season with the agreement of their Chief Constable. They came not only from the Metropolitan Force, but also from Cheshire, Colchester, Greenock, Norfolk, Dundee, Preston and Birmingham and possibly other locations as well, where documents no longer exist. It was crucial that ploughing obtained skilled men, as much of the ground identified in the plough policy had not been previously ploughed, so that it was heavy and needed strong, skilled men to guide the manual plough sufficiently deeply into the soil to turn it. Many policemen were previously employed in agriculture and had ploughing skills, as well as having strong physiques.

The police as ploughmen were said to be so successful that they were asked to return temporarily for the harvest in 1917 and for the planting season and harvest again in 1918. The police augmented other temporary and permanent workers on the land such as soldiers, prisoners, women and school children. The result of this reallocation of labour to the land was that by 1918 despite the shortage of skilled agricultural labour, particularly ploughmen, the temporary workers, including policemen, had increased crops such as cereals and potatoes by 57% above pre-war levels, and although the government’s ploughing targets were not met, an additional 2,966,000 acres of grassland in Britain had been turned over to grain and root crops.

The picture below shows the kinds of equipment the police worked with to turn pasture land over to growing crops. The land they worked would have been previously unploughed and so much more difficult to turn over than this picture shows.

Suggested reading

Dewey, P. E. (1989) British Agriculture in the First World War. London and New York: Routledge.

Ernle, R.E. P. (1925) The Land and its People: Chapters in Rural Life and History. London: Hutchison & Co. https://archive.org/details/landitspeoplecha00ernluoft

Ernle, R.E. Prothero, (1961) English Farming Past and Present. Sixth Edition. London: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd

Grieves, K. (1988) The Politics of Manpower, 1914-18. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Scott, C. (2017) Holding the Home Front: the women’s land army in the First World War. Barnsley: Pen and Sword History

Contributed by Mary Fraser, PhD

Blog https://writingpolicehistory.blogspot.co.uk

Forthcoming book Policing the Home Front in Britain, 1914-1918. Due to be published by Routledge as a Research Monograph, part of the Taylor and Francis group, see http://208.254.74.112/books/details/9781138565241