Food and the First World War

Contributed by Rachel Duffett

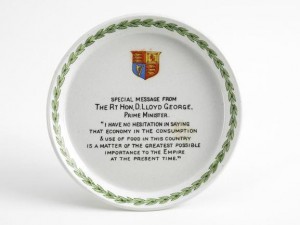

The First World War was a total war: the home front became the frontline and unprecedented levels of commitment to the nation’s war effort were demanded of its civilians. In addition to the toil in factories and on the land and the emotional sacrifices resulting from the absence of men from their families, those at home faced four years of rising food prices accompanied by shrinking supplies. The butter dish in the photograph to the right is evidence of both that involvement and those shortages – on the back it’s described as being ‘For a family of ten’ even though it’s only 11cm in diameter. Lloyd George’s words make the point that limited resources necessitate limited consumption, but the reverse of the dish makes the commitment of the whole population even clearer: ‘Made by the girls of Staffordshire during the winter of 1917 when the boys were in the trenches fighting for liberty and civilisation.’ The dish embodies the different sacrifices made: the men in the battlefield, the women filling their places in the workplace and the families across the country who were required to demonstrate their resolution at the dinner table.

The First World War was a total war: the home front became the frontline and unprecedented levels of commitment to the nation’s war effort were demanded of its civilians. In addition to the toil in factories and on the land and the emotional sacrifices resulting from the absence of men from their families, those at home faced four years of rising food prices accompanied by shrinking supplies. The butter dish in the photograph to the right is evidence of both that involvement and those shortages – on the back it’s described as being ‘For a family of ten’ even though it’s only 11cm in diameter. Lloyd George’s words make the point that limited resources necessitate limited consumption, but the reverse of the dish makes the commitment of the whole population even clearer: ‘Made by the girls of Staffordshire during the winter of 1917 when the boys were in the trenches fighting for liberty and civilisation.’ The dish embodies the different sacrifices made: the men in the battlefield, the women filling their places in the workplace and the families across the country who were required to demonstrate their resolution at the dinner table.

Food Supplies

When war was declared, a rash of panic buying broke out and food supplies came under pressure as people hoarded goods. Michael McDonagh, a London journalist recorded in a diary entry for August 5 1914, the early closure of several food shops in his Clapham neighbourhood after they had been emptied by anxious shoppers.[i] Fears about availability were felt across the country and Harry Cartmell, the Mayor of Preston, felt compelled to issue a warning bulletin to the town, stating ‘we must condemn the selfishness, almost criminal, of those who have been appropriating the commodities of life to the detriment of the community…’.[ii]

In 1914, Britain relied heavily on food from abroad – 80% of wheat, 40% of meat and almost all sugar was imported – but the government was reluctant to get involved in such matters, feeling that it was best that the market should be left to operate free of state restrictions. Other than the setting up of two commissions, one on wheat and the other on sugar, laissez-faire worked for the first two years of the war, but by the summer of 1916 food problems were becoming sufficiently pressing to require greater intervention. The public’s main concern was prices and the Board of Trade’s figures show a 61% increase in food prices between July 1914 and July 1916.[iii]

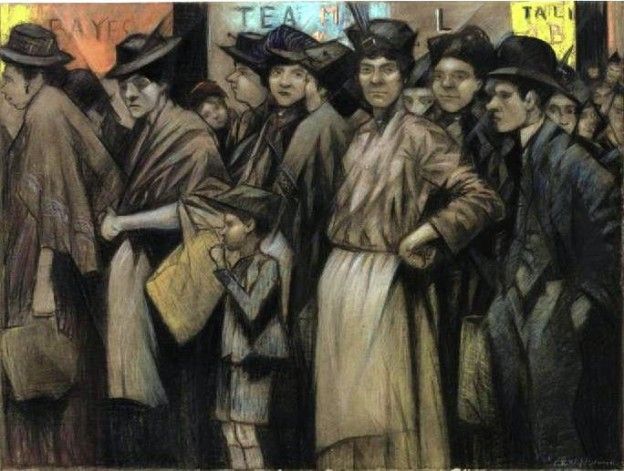

Many believed that the call for national sacrifice had not been heeded by all and there were some who were making money from the war. The exploiters of workers – in both factories and trenches – were despised and Trades Union newspapers labelled the profiteer as ‘The Vampire on the Back of Tommy’ and the ‘Brit-Hun’. Shortages, high prices and inequalities of food distribution became a real concern for many in Britain during 1916. Poor harvests meant that even staples like potatoes were in short supply and, as they were the only vegetable that many of the urbanised poor ever ate, there were outbreaks of scurvy in Manchester, Newcastle and Glasgow. [iv] Finally, in December of that year the government responded to complaints and concerns by appointing Lord Devonport as Food Controller.

Rationing

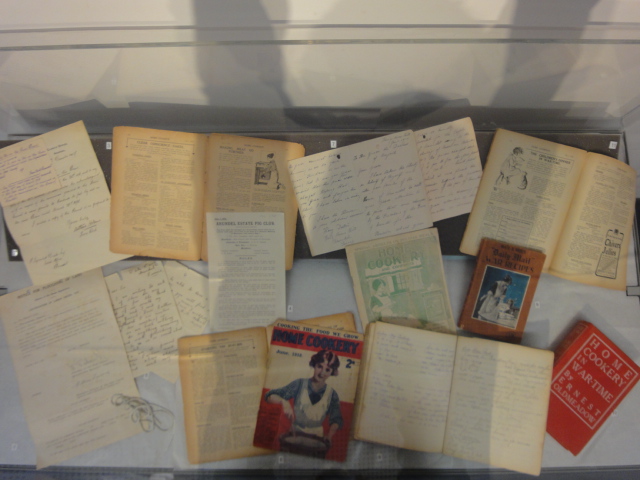

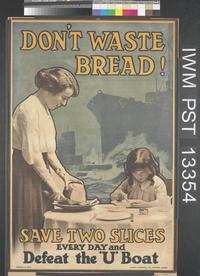

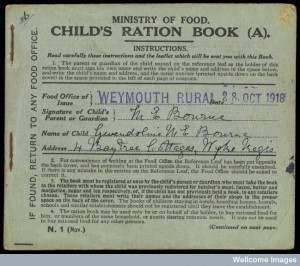

The idea of rationing was alien and it was felt that a system of voluntary restraint would be sufficient. In March 1917, J. Hollister wrote to his father ‘things in London beginning to be serious, no potatoes to be had, sugar almost unobtainable, meat and cheese 1/6, butter 2/4, bread 11d.’[v] Solutions were urgently needed, but Devonport’s ideas were not based on sound nutritional knowledge, his suggestion in April 1917 that people should eat no more than 4 lb. of bread, 2½ lb. of meat and ¾ lb. of sugar a week was unrealistic resulting as it did in only c1,300 calories a day when the other foodstuffs needed to supplement these basics were, if available, very expensive. The intensification of the German U-boat campaign precipitated a crisis when in the spring of 1917 it was announced to the House of Commons that the nation’s stocks of food had dwindled to only three or four week’s supply. Action was needed and following Devonport’s resignation in May. Lord Rhondda was appointed whose policies recognised the need for stricter controls in a situation where individual voluntary efforts were never going to be sufficient.

The idea of rationing was alien and it was felt that a system of voluntary restraint would be sufficient. In March 1917, J. Hollister wrote to his father ‘things in London beginning to be serious, no potatoes to be had, sugar almost unobtainable, meat and cheese 1/6, butter 2/4, bread 11d.’[v] Solutions were urgently needed, but Devonport’s ideas were not based on sound nutritional knowledge, his suggestion in April 1917 that people should eat no more than 4 lb. of bread, 2½ lb. of meat and ¾ lb. of sugar a week was unrealistic resulting as it did in only c1,300 calories a day when the other foodstuffs needed to supplement these basics were, if available, very expensive. The intensification of the German U-boat campaign precipitated a crisis when in the spring of 1917 it was announced to the House of Commons that the nation’s stocks of food had dwindled to only three or four week’s supply. Action was needed and following Devonport’s resignation in May. Lord Rhondda was appointed whose policies recognised the need for stricter controls in a situation where individual voluntary efforts were never going to be sufficient.

A national sugar rationing scheme began in January 1918, it worked well with everyone receiving half a pound a week, but the success of the venture was overshadowed by the difficulties in obtaining other foods.

Edie Bennett lived in Walthamstow and her letters to her husband serving in Mesopotamia make the pressures all too clear, in January 1918 she wrote: ‘I have no good news to tell you as things here are getting in a terrible state’ and described queuing for over two hours for cheese which was sold out by the time she got to the counter.[vi] The men on active service were made aware of the problems at home and it is clear from investigations into military morale that their concerns about their families had a negative impact. By April 1918, rationing had been extended to include:

too clear, in January 1918 she wrote: ‘I have no good news to tell you as things here are getting in a terrible state’ and described queuing for over two hours for cheese which was sold out by the time she got to the counter.[vi] The men on active service were made aware of the problems at home and it is clear from investigations into military morale that their concerns about their families had a negative impact. By April 1918, rationing had been extended to include:

- butter and margarine 5 oz. per week

- jam 4 oz. per week

- tea 2 oz. per week

- bacon 8 oz. per week (16 oz. after July 1918)

- fresh meat rationed by price.[vii]

Food Production

In addition, greater effort was put into food production and while we might think of ‘Dig for Victory’ as being a WW2 slogan it was part of the First World War home front too and the photograph shows the Rev. J. Walton blessing the war allotments in Croydon in an effort to further increase the nation’s harvest.

Lord Rhondda’s management of food supplies, which included a commitment to limiting increases in the prices of basic items, was successful and the food queues with their associated sense of outrage and injustice featured less often in daily life. Of course, the ideas and actions that were first explored in 1914-1918 were to prove especially useful two decades later when Britain was to once again face a key challenge of total war – hunger on the home front.

References

[i] Michael MacDonagh, In London During the Great War. The Diary of a Journalist (London, 1935), entry dated 5.8.1914.

[ii] H. Cartmell, For Remembrance (Preston, 1919), p. 30.

[iii] Ian F.W. Beckett, Home Front, 1914-1918. How Britain Survived the Great War (Richmond, 2006), p. 110.

[iv] John Walton, Fish and Chips & the British Working Class 1870-1940, (Leicester, 1992), p. 158.

[v] J. Hollister, IWM 98/10/1, letter dated 19.3.1917.

[vi] E.S. Bennett, IWM 96/3/1, letter dated 24.1.1918.

[vii] John Burnett, Plenty and Want. A Social History of Diet in England from 1815 to the Present Day (London, 1979), p. 276.

Useful Further Reading

Beckett, Ian F.W.. Home Front, 1914-1918. How Britain Survived the Great War (Richmond, 2006).

Burnett, John. Plenty and Want. A Social History of Diet in England from 1815 to the Present Day (London, 1979).

Cartmell, H.. For Remembrance (Preston, 1919).

Duffett, Rachel. The Stomach for Fighting: Food and the Soldiers of the Great War (Manchester, 2012).

Imperial War Museum Collection, letters of E.S. Bennett (96/3/1) and J Hollister (IWM 98/10/1).

MacDonagh, Michael. In London During the Great War. The Diary of a Journalist (London, 1935).

Marwick, Arthur, The Deluge (London, 1991).

Walton, John. Fish and Chips & the British Working Class 1870-1940, (Leicester, 1992).