Dr Paul Cleave is a freelance researcher. His current research at the University of Exeter focuses on the social history of twentieth century tourism in the United Kingdom. He is also interested in the food history of the twentieth century, and the role of women on the Home Front during the First World War.

Cookery books from the First World War tell us much about the diet of the period, and how the population at home coped with food shortages. The books were good for morale, demonstrating how sensible cookery, Innovation, and imagination could make the best of very little.

The Best Way Cookery Book, ca 1916, advised – ‘There are soldiers in the little homes all over England as well as soldiers in the trenches, housewife soldiers, with no deadlier weapon than frying pan and saucepan, yet with the true brave spirit, can help their country by saving every penny and making war-time meals as appetising as in times of peace, at half the cost’. Readers were instructed how to make eggless cakes and puddings, cook frost bitten potatoes, and to use dripping instead of butter.

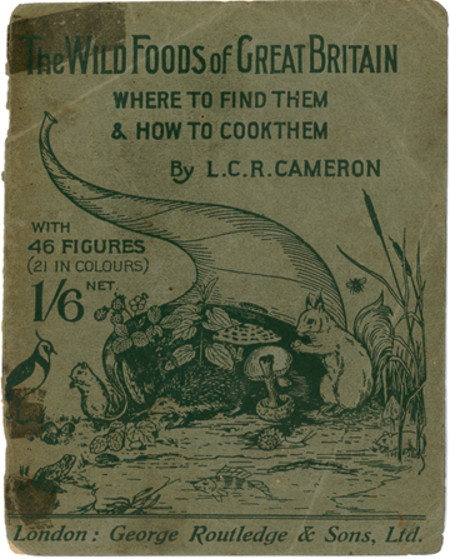

Cameron’s The wild foods of Great Britain, 1917, encouraged foraging, and gathering food from field and hedgerow. It was suggested that herbs, mushrooms and berries were available to all at a time of food shortages and high prices.

The introduction advised readers:

‘The incidence of war has bought home to its inhabitants that an island like Britain is not self supporting, and that scarcity, if not actual want of daily food is daily becoming more possible, if not probable. This little book makes no pretence to be anything but a severely practical guide for the use of the ordinary man, woman or child.

It is not intended that everything contained in this manual will be to the taste of everybody. Neither is everything on the menu of Romano’s or the Ritz Hotel always to the taste of all the patrons of these metropolitan refreshment houses’.

Among the ‘two hundred and sixty kinds of Wild Food to be gathered freely in Great Britain’, Cameron describes the merits of snails, edible frogs, and hedgehogs. Readers are reminded that seaweeds under the names of Dulse and Laver were highly nutritious. Laver bread (the cooked seaweed) was noted as having been offered for sale to summer visitors, and even in the farmhouses of North Devon it is commonly eaten as a vegetable or salad. Garlic, allium ursinum, ‘ramsons’, was recorded as common in woods and thickets, and could be used instead of cultivated, imported garlic. A substitute for tea was included, made from the dried flowers of the Lime tree, and producing ‘a pale delicately scented liquor, best drunk in tea cups with sugar, and a small piece of lemon, as tea is usually served in Russia’.

Elizabeth Craig writing in Cooking in war-time c 1940, included recipes sent to her during the First World War from a soldier cook, Rag time Joe, as an example in ‘making do’ for the Second World War. His recipes from the front included Trench Mortar, a mixture of crushed Army biscuits and plum jam served warm every night for supper. A 1916 Trench Cake, an economical fruit cake flavoured with cocoa and ginger provided another sweet treat.

War-time cookery books are more than a collection of recipes; they are a social commentary, showing ways in which the housewife helped the war effort in the kitchen.

Cameron, L, C, R., 1917, The Wild foods of great Britain, London, Routledge.

Anon c1916, The Best Way Cookery Book, No 3, London, Amalgamated Press.

Craig, E., c1940, Cooking in war-time, Glasgow, The Literary Press.

Dr Paul Cleave