6 August 2014

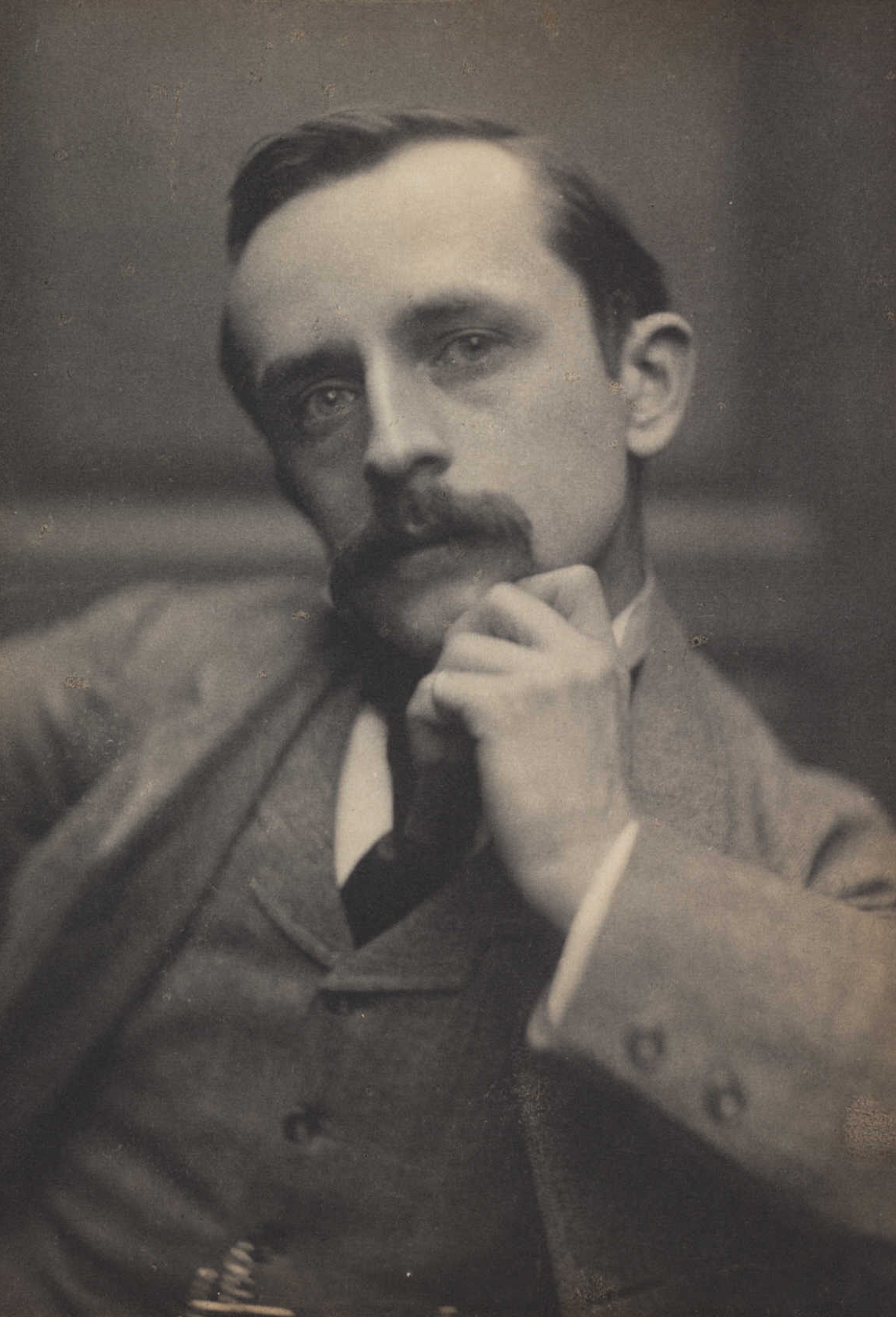

As part of a longer term project of reviving forgotten First World War plays, the Everyday Lives in War centre presented J.M. Barrie’s one-act play, A Well-Remembered Voice at the Weston Auditorium. This was the first production of the play since its premiere in 1918.

Aim

Working with IO Theatre, we wanted to see how Barrie’s play stood the test of time and how a small company of four actors working to a tight budget might bring it to life. The results can be seen in this clip.

Background

J.M.Barrie (1860-1937) wrote several plays during the war, some touching on war subjects. These included. Der Tag (1914), The Last Word (1915), The Old Lady Shows her Medals (1917). A Well-Remembered Voice. One of Barrie’s most famous plays, Dear Brutus – about second chances – opened in 1917.

A Well-Remembered Voice premiered on Friday 28 June 1918 at Wyndham’s Theatre. It was part of a triple Barrie bill in aid of the Countess of Lytton’s hospital for wounded soldiers at 37 Charles Street, Mayfair. This was a very fashionable charitable event by all accounts. The 3 pieces were La Politesse – a comic piece about 2 cockney soldiers lost in France; a children’s fantasia The Origin of Harlequin, in which various aristocratic children performed; and finally A Well-Remembered Voice, which was regarded by those who saw it as the high point of the event. The actors Gladys Cooper and Sir Charles Hawtrey then auctioned off a new portrait of the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, getting £250.00 for it.

Barrie was an influential theatrical figure and was able to assemble a prestigious cast for A Well-Remembered Voice including Sir Johnston Forbes Robertson, Lillian Braithwaite, Faith Celli and George Du Maurier. The resulting play was rapturously received. The Era (3 July 1918) wrote:

‘A Well-Remembered Voice’ handles with gentle fingers the loss of young life at the front and the desire of the bereaved to know that all is well with their dead. It begins with table-tapping, the father sitting unbelieving while the others try the machinery of spiritualism; it ends with a talk à deux between this startled father and the young voice he so much misses – just a talk about simple domestic things, sport and dogs and father’s pipe and cheery words of comfort and affection… A memorable afternoon!’

The play’s theme of spiritualism was obviously very current in 1918; by this stage of the war the idea that there was a spirit world was an appealing one, not surprisingly given the loss of so much life. Barrie’s contemporary, Arthur Conan Doyle did tours promoting spiritualism. Doyle’s dead son Kingsley (d.1918) appeared to him during a séance in 1919 telling his father that he was content on the other side and that his father should not grieve. This is one of the messages of Barrie’s play. Of course, J.M. Barrie himself was devoted guardian to the 5 Llewelyn Davies boys – often seen as the originals for the `lost’ boys of Peter Pan. In March 1915 George Llewelyn Davies was killed in Flanders. Thus A Well-Remembered Voice might also be read biographically, as Barrie’s writing out his own grief; his feeling that the war was not ‘an awfully big adventure’ but a catastrophe.

Why we chose it

A Well-Remembered Voice reads like a polite, chatty drawing-room drama but it deals with some of the big themes of the conflict as experienced on the Home Front – loss, mourning, remembrance, belief, parents outliving their children. There is much that is unspoken, in particular the sense of a family trying to contain their grief at the same time as it dominates their lives. In the published version of the play Barrie is also very explicit in his stage directions. One of the things which the creative team involved in this new production wanted to do was to try and convey something of Barrie’s methods. Thus, as the clip shows, the actors step and in and out of character, explaining the action and each character’s thoughts. The team also wanted to try to encourage different perspectives on Barrie’s play, to convey something of its complexity – is the play a form of propaganda? – and to show how First World War plays needn’t be staged only as they appear on the page but can be updated and revisioned for modern audiences using a range of lighting, musical and performance styles.

Future plans

Given the positive responses to this production, our plan is to show it to a wider audience both in and beyond Hertfordshire; to use it as a basis for workshops with schools and special-interest groups; and also to use it as a working example of how First World War plays might be adapted and reimagined. The first workshops will take place in the autumn.