Contributed by Andrew Maunder

As the Finborough Theatre revives John Galsworthy’s comedy Windows as part of its Great War 100 series, it’s worth thinking more about the play’s Nobel Prize-winning author and his principled stand between 1914 and 1918.

Awakened at 2.15 by Ada – sound of guns. Got up and watched searchlights and shrapnel on Zep, and about 2.23 a Zep on fire, brought down. Glad to say that enthusiasm did not quite prevent feeling for the thirty men roasting in the air. We went out and talked a few minutes to some policemen; the great cheering in the streets was over and they were empty.

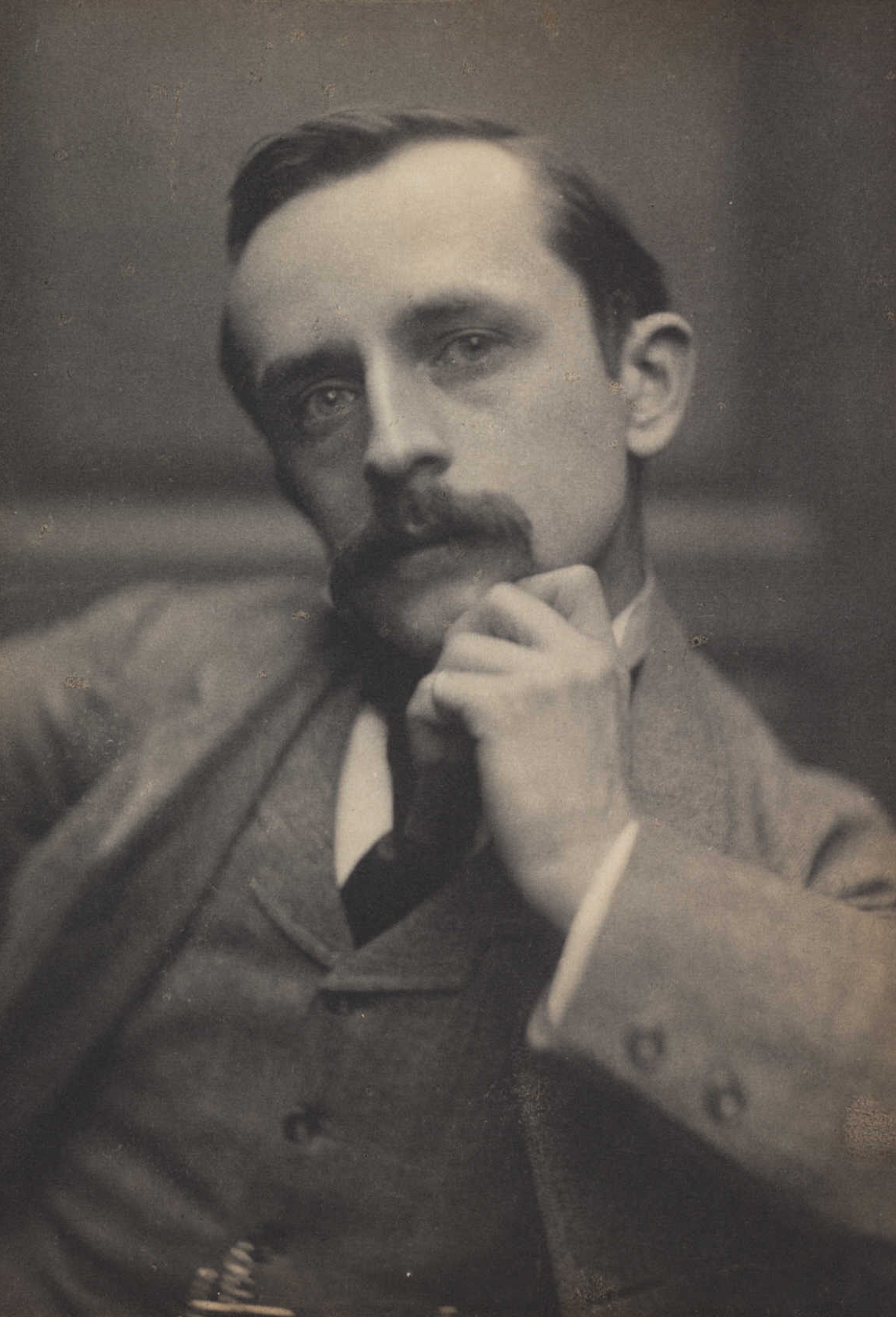

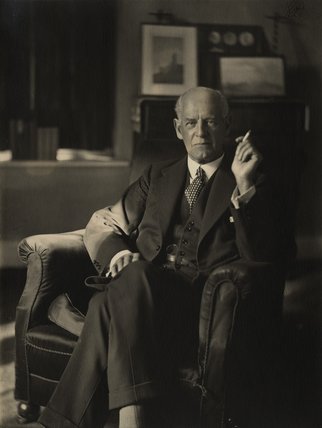

This is John Galsworthy (1867-1933) writing in his diary on 3 September 1916. A lawyer by training with a strong social conscience, Galsworthy is generally known for the series of novels comprising The Forsyte Saga, the first volume of which, The Man of Property appeared in 1906 and which has been televised twice. Galsworthy was also a playwright known for socially conscious plays such as Strife (1909) and Justice (1910). At time of his being woken up by the Zeppelin, The Foundations, a vision of post-war discontent and class bitterness had just premiered at London’s Royalty Theatre.

This is John Galsworthy (1867-1933) writing in his diary on 3 September 1916. A lawyer by training with a strong social conscience, Galsworthy is generally known for the series of novels comprising The Forsyte Saga, the first volume of which, The Man of Property appeared in 1906 and which has been televised twice. Galsworthy was also a playwright known for socially conscious plays such as Strife (1909) and Justice (1910). At time of his being woken up by the Zeppelin, The Foundations, a vision of post-war discontent and class bitterness had just premiered at London’s Royalty Theatre.

During the war Galsworthy felt that that the British people were being brain-washed by newspapers and politicians into seeing the conflict as something glorious when in actual fact it was a terrible disaster. In `Our Literature and the War’ (1916) he denied that war was glamorous or glorious but rather `something spasmodic, feverish, and almost false; a kind of deep and tragic inconsistency.’ In another piece `Deeds and Silence’ (1915-16) he reserves his harshest censure for the violent rhetoric used to describe the enemy – the seeming inability of writers like Rudyard Kipling to describe them as anything other than pure evil.

Despite his distaste, Galsworthy felt it his duty to get involved. His wife, Ada, called her husband “the Appeal writer par excellence.” By 7 November 1914 he had given £1,250 worth of donations earned by his pen. Galsworthy wrote compulsively, turning out swathes of fiction, journalism and drama:

“In cool blood I suppose what I am doing – that is writing on – novels and stories – and devoting all I can make, especially from America – no mean sum – to Relief – is being of more use than attempting to mismanage Relief Funds, or stretcher bearing at some hospital, or even training my elderly unfit body in some elderly corps.”

Post-1919 Galsworthy remained convinced that the public had been brain-washed into seeing the war as something glorious when in actual fact it was a terrible disaster. His novel The Burning Spear (1919) is an attack on propaganda and helped cement the idea in some people’s minds of Galsworthy as the ambassador for a kind of hand-wringing, woolly liberalism or socialism and, even worse, a pacifist! A 1920 short story collection Tatterdemalion (the title means something worn-out, damaged or spoiled) is a roll-call of unfashionable war victims. In the most powerful story “Defeat” (published in America in 1917 but not in Britain) a young captain on leave is picked up by a German prostitute after a Beethoven concert. The woman is doubly an outsider – fallen woman and enemy alien who passes herself off as Russian for fear of being lynched by patriotic Londoners. As an outsider she is credited by Galsworthy with having a unique perspective how the war is presented to the people by politicians and journalists:

Post-1919 Galsworthy remained convinced that the public had been brain-washed into seeing the war as something glorious when in actual fact it was a terrible disaster. His novel The Burning Spear (1919) is an attack on propaganda and helped cement the idea in some people’s minds of Galsworthy as the ambassador for a kind of hand-wringing, woolly liberalism or socialism and, even worse, a pacifist! A 1920 short story collection Tatterdemalion (the title means something worn-out, damaged or spoiled) is a roll-call of unfashionable war victims. In the most powerful story “Defeat” (published in America in 1917 but not in Britain) a young captain on leave is picked up by a German prostitute after a Beethoven concert. The woman is doubly an outsider – fallen woman and enemy alien who passes herself off as Russian for fear of being lynched by patriotic Londoners. As an outsider she is credited by Galsworthy with having a unique perspective how the war is presented to the people by politicians and journalists:

“the men who think themselves great and good, and make the war with their talk and their hate, killing us all – killing all the boys like you…and telling us to go on hating; and all those dreadful cold-blooded creatures who write in the newspapers – the same in my country, just the same…”

She goes onto to dismiss terms like “comrade” and “brotherhood’” as labels sold to men like the captain in order to keep them fighting. “You think’, she tells him scornfully, ` the war is fought for the future: you are giving your lives for a better world, aren’t you?”

Windows

First seen at London’s Court Theatre in April 1922, it will be interesting to see whether the revival of Windows at the Finborough Theatre will help revive interest in Galsworthy – this socially-conscious and very skillful writer who was always interested in what he called “the tides of inequality” which sweep over people.

In 1922, Windows was not one of Galsworthy’s most successful plays; it’s a comic and satiric work and audiences weren’t sure what message to take away. But it takes the audience into familiar Galsworthy territory; it’s socially conscious and tries to challenge complacency. There’s a wealthy novelist, Geoffrey March – a self-portrait of Galsworthy himself perhaps – who “has an open mind and hates the Government.” His idealism is tested when his son, a war poet, falls for the family’s new housemaid, Faith. She is just released from jail after serving two years for killing her illegitimate baby. She is hardly a desirable daughter-in-law. Should the family intervene? Their liberal instincts tell them that the girl is a victim – someone whom society prefers not to think about. But she is also a schemer, quite ready to “go to the devil” if chances arise; they’d rather not have her as one of themselves thank you very much!

After a good deal of angst, it’s left to the housemaid’s father, a window-cleaner, to dispense home-spun philosophy whilst the family realize that Faith “just— wants—to—be—loved.” But who or what she loves, or does, is not something they can dictate – as they might have done before 1914.

Windows runs 22nd August – 9th September 2017. Tickets available via the Finborough Theatre website. http://www.finboroughtheatre.co.uk/productions/2017/windows.php