Barry Edwards has been researching the life and work of playwright Gertrude Jennings. She was a successful writer whose plays have been unjustly neglected since the peak of her fame in the first third of the twentieth century. Here Barry describes his experiences as a director for Optik Theatre Company staging some of Jennings’ work in 2014 and 2015. As he explains, the plays take in many of the everyday concerns and niggles of those living during the conflict, as well as standing up as well-crafted pieces of writing – long over-due for re-evaluation.

In 2014 with my company Optik I embarked on a project to revive the work of playwright Gertrude Jennings (1877 – 1958). She was actively engaged in the professional London theatre scene from early in the 20th century until well into the 1930s and beyond. She wrote over fifty plays ranging from one-act comedies to full-length works, all performed in the main theatre houses of central London (Prince of Wales’ Theatre, Haymarket, Strand Theatre, Ambassadors). To date Optik has produced two seasons of her work: Between the Soup and the Savoury (1910) and Pros and Cons (1912) in 2014 and Five Birds in a Cage (1915) and The New Poor (1919) in 2015. Both of these seasons were presented as part of the World War One Centenary Commemoration programme funded by the London Borough of Richmond Upon Thames.

Her plays are brilliant satirical pieces that combine comedy, farce and provocative social commentary. Bringing them back to life in rehearsal and production has revealed the sheer physical theatricality of her work. It is fair to say she was a pioneer of women’s writing and women’s contribution to the theatre generally. It still comes as a surprise that she has been largely forgotten and her work unperformed for decades. Too easily dismissed under the genre of ‘light comedy’ her plays demonstrate that comedy is indeed a serious matter and when taken seriously Jennings is a devastating critic of hypocrisy, greed and the abuse of position.

Gertrude Jennings was born in 1877, the daughter of Louis Jennings who was editor of the New York Times before becoming MP for Stockport and Madeleine Henriques, an American actress known for her work at New York’s Wallack’s theatre. Gertrude began her theatrical career as an actress, performing in New York under the name Gertrude Henriques and then touring in productions of English classical works with the Ben Greet Players.

Her 1912 play A Woman’s Influence brought her recognition within the Actresses Franchise League as it became one of the organisation’s most popular and frequently performed plays. Its theme of conflict and confusion between the sexes is one that Jennings works with again and again. In her earlier play Pros and Cons (1911) a precociously intelligent young 17 year old (Evangeline) is making notes as she witnesses the on-going wrangling between her cousin Brenda and her husband Freddie. Jennings’ comic skill is to place the origin of the conflict in something trivial: the use of the telephone. In a nod to the spurious list of ‘benefits’ of marriage listed in Cicely Hamilton’s influential book Marriage as a Trade (1909), Evangeline is drawing up the ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ of marriage, and unsurprisingly has a long list of ‘cons’ but only a few ‘pros’:

EVANGELINE Arguments in favour or marriage. 1. ‘No-one can say you haven’t been asked’. 2. ‘There is always someone in case of burglars’. 3. ‘ You can get a complete set of new clothes’.

At the outbreak of war the AFL disbanded and activists such as Lena Ashwell – manager of the Kingsway Theatre London – led the drive to provide entertainment to the troops. By 1917 there were 25 companies performing over 1400 shows a month. Material was drawn from classic and contemporary writers such as Shaw, Sheridan and Barrie, with Lena Ashwell being particularly enthusiastic about taking Shakespeare to the front line soldiers. Jennings formed her own company and travelled to France where it is likely she also produced her own sketches and one act plays written during this period. In 1914 Samuel French had already published a collected volume of her plays under the title Four One Act Plays. These were Between the Soup and the Savoury, Acid Drops, Pros and Cons and The Rest Cure. During the war itself she wrote Five Birds in a Cage, The Bathroom Door, Keeping Up Appearances, Poached Eggs and Pearls – a canteen comedy, Allotments, At the Ribbon Counter, No Servants, and Waiting for the Bus.

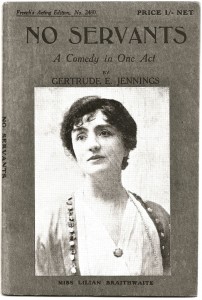

These plays were also performed for the home front in London with full professional casts. No Servants, for example, was performed in April 1917 at the Princes Theatre with Lilian Braithwaite starring in the lead role as Victoria.

Five Birds in a Cage opened on March 19 1915 at the Haymarket Theatre then returned as part of the evening bill on April 20 and ran for 284 consecutive performances.

None of Jennings’ sketches and plays performed during the war make any overt reference to the conflict. Comedy and entertainment were priorities. Shortly after the war, however, she did write two plays that referred directly to the war. In The New Poor (1919) a family in the top echelons of landed aristocracy find themselves destitute when the father dies more or less penniless. They are the ‘new poor’ – the 1919 equivalent of ‘asset rich, cash poor’. The housing crisis in London is so acute after the war (an issue reverberating back into the present day) that the family of brother and two sisters are forced to share a house with the formidable landlady Mrs Buckle. Mrs Buckle is ‘new rich’ – the widow of a northern industrialist who made a fortune manufacturing braces for the army during the war (Bradford mill owners were given substantial equipment orders). In the Cellar (1920) is set in 1917 and features a pompous newly elevated Lord Kidderminster (a business man who has paid for his peerage) who it transpires has been hording tins of food and tea in his cellar. A young servant boy whose father is on the war-time Food Committee witnesses the discovery of his illegal horde. To escape being turned in and facing a certain jail sentence his Lordship is forced to climb down on every issue he’d been resisting, from his daughter’s romance with a soldier to the young servant’s promotion. The servants decide to distribute the food around the local community.

Gertrude Jennings continued to write plays into the 1950s, including full-length plays such as The Young Person in Pink (Prince of Wales’ Theatre 1920) with the 20 year old Joyce Carey in the cast. The play was later turned into a film The Girl Who Forgot (1939) directed by Adrian Brunel. The synopsis on the BFI database gives a real flavour of Jennings’ sense of the absurd and the comic:

‘Girl loses her memory on train on way to see her parents off to Bagdad. She ends up at the Ritz Carlton Hotel where a series of complications arise but all eventually ends well.’

Her full-length play Family Affairs (1934) starred Lilian Braithwaite once more, playing the elderly family matriarch Lady Madehurst, who is being pressured by her family to sell her house and be taken care of (demonstrating that care of the elderly and its financing is not just a contemporary issue).

It is in her earlier work, however, especially those written just before, during and just after World War One, where her special quality is most accessible and apparent.

Her situations are rooted in the everyday and the absurdities that humans find themselves in, mostly of their own making. In the tradition of physical farce ordinary household objects play a key role: pots, pans, furniture, a stuffed fox, shoes, hats, secret notes. Jennings excels in dramatizing the routine but essential activity of living and getting by – keeping warm, dealing with a cold, sharing a room, dealing with (often petty) arguments, and naturally the business of meal-times, food and cooking.

Cooking -and all the related activity around preparation -was a particular favourite of Jennings. Vera and Mrs Buckle in The New Poor nearly come to blows over cooking a pan of kippers on the coal fire. No Servants centres on an evening meal that Victoria wants to have with the man she fancies, Harris. When all the servants leave (for better jobs outside of service) she has to try and cook herself. Needless to say it all goes horribly wrong and they end up eating cheese and biscuits, but not before a fully feathered duck has been put in the oven. Her early play Between the Soup and the Savoury consists entirely of a cook and two servants preparing, cooking and dishing up a full course meal for the ‘Greedy, guzzling pigs’ upstairs.

Food, shelter, work and romance – the basic ingredients of everyday life you might say – these are the core elements in her narratives. What then turns them into exquisite pieces of comic performance is the essential ingredient of human conflict. A conflict that is played out on two distinct fronts: the English class system and the competing needs and ambitions of women in their relations to men. It is a given that class is a gift to comedy and Jennings exploits this to the full. She is adept at clashing the different levels of social class together, sometimes literally as in the hilarious Five Birds in a Cage. The Duchess of Wiltshire, who writes pamphlets on socialism and the ‘brotherhood of man’, is stuck in a broken down lift on the underground. Her fellow passengers in the lift include her companion Lord Porth, Bert a bricklayer, Nelly a young servant woman and (naturally) Horace, the liftman. The servant girl and the Duchess almost come to blows – and this is typical of Jennings’ style: class difference is no barrier to telling it like it is. When Nelly finds the Duchess’ attitude too much to take she doesn’t hold back.

NELLY It’s selfish – it’s cruel. I hate ladies. I never want to be a lady as long as I live – never!

This is in sharp contrast to the Duchess’ panicky proclamation that they are to all perish together in a ‘wonderful example of Brotherhood’. Once the lift is working again all this is forgotten and the Duchess, as we all anticipate, quickly reverts to asserting her privileged status.

When push comes to shove it is always the women in Jennings’ work who are the key protagonists driving the play along. Often it is those who are struggling to cope and make the most of their situation – tough though it may be – as is Vera in The New Poor battling to keep her family together. In her work as whole roles for women outnumber those for men by 2 to 1, with many plays having only one male role and several calling for all female casts.

It is tempting to argue that there is a Brechtian edge to Jennings’ theatre in the way she constructs her narratives and situations. Her characters are rooted in the economic circumstances they find themselves in- rich or poor, servant or Lady. Her characters all act out of a sense of self-interest or self-reliance –and this involves surviving, often competing and never giving in. No one single character has the authorial voice – the plays are built around a strong will to survive, to ‘get on’ and prosper and yes, to find, deal with or sometimes (as in Pros and Cons) threaten to leave a sexual partner.

In this way the plays of the war years reveal a lot about social attitudes at the time. Far from being conservative or restrained, Jennings’ work is full of anger, yearning, fear and struggle. There is very little, if any sense of despair, and a very real, if implied, sense of optimism or confidence in the future. No one calls on a higher ideal (justice, rights) to remedy the way things are. If there are opportunities you take them, if there are obstacles you fight them, if you have a chance to make a life with someone, you go for it. In No Servants the domestic team tell Victoria one by one why they are leaving – they have all got work in the growing non-domestic jobs market: one is taking over a sausage shop, one is going to be a policeman and one is going on the stage (support from Jennings for seeing acting as a professional job!). Times are changing, yes, but Jennings suggests that whatever happens people will always have conflict, there will always be disputes but that is the human comedy. You have to accept that, laugh at and with it, and admire the human spirit that keeps pursuing that dream despite it all.

Love Work and the Vote 2014 Optik

Director Barry Edwards

Design Giles Chiplin

A Gertrude Jennings Double Bill 2015 Optik

Director Barry Edwards

Design Giles Chiplin

Full cast details and further information on www.gertrudejennings.com

© Barry Edwards 2016