Contributed by Dr Ciara Meehan, project Principal Investigator.

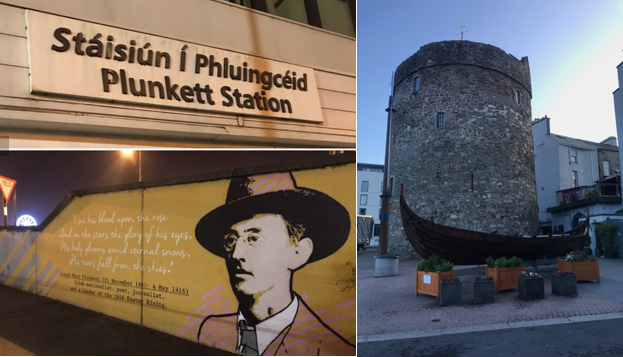

As you step off the train in Waterford, you can’t escape history. The train station is named after Joseph Mary Plunkett, one of the executed leaders of the 1916 Rising. He is further commemorated in a mural directly opposite the station. A short stroll across the bridge and the city’s Viking heritage is apparent. Waterford is a county steeped in history. And, as I discussed in my last post, there was a strong response from the men of Waterford to calls to serve in the British army during the First World War.

Those in attendance at the workshop were very interested in the process of commemoration, rather than having a direct personal connection. One man had visited battle sites in France, and he was planning another trip. For him, commemoration and remembrance were important. He felt that the Anglican community was, perhaps, more at ease when it came to commemoration. Originally from Bristol, he moved to Waterford in the 1960s. His nationality, he thought, probably had a bearing on his life-long interest in the war and commemoration.

Though another woman in attendance recalled cross-community commemorations held at a CoI church in Fermoy, Co Cork, she noted that, on the whole, commemoration in Cork (where she was originally from) was far more low-key than what she observed in the UK. As she put it in terms of that County’s relationship to the war, ‘they chose to forget’. She also explained that she hadn’t thought about wearing the poppy before living in England as a student – a further insight into the bearing that location has on people’s relationship to this sensitive symbol.

Though it seems an obvious point, these workshops have repeatedly confirmed that, whilst Irish attitudes towards service in the war has evolved, at local level there has been something of a struggle to get to that stage. Identity, nationality, religion, geography are all factors bound together in the relationship to commemoration.

Participants in the workshop were keen to ask the question, ‘when does commemoration stop?’ Given that we were in Ireland, in the midst of a decade of commemoration, it is inevitable that thinking about the First World War would be viewed in the wider context. Are Irish people fatigued? Is a decade too long?, asked one woman. But the question about when it stops was asked, not just in the context of length of time, but also in terms of events that are chosen to be marked. A general commemoration, held on one single day, was suggested as an alternative – a day when we remember people, rather than events.

This subject of length and focus, more than anything else, dominated our workshop. For me, it was the real take-away of the event. If the Engagement Centres are now thinking about what we’ve learned from the commemoration period, timing, duration and what exactly is commemorated are clearly factors to consider.