Contributed by Dr Ciara Meehan, project Principal Investigator.

In my last post, I wrote about my planned visit to Enniskillen for the Northern Irish-leg of this workshop tour. I got the bus up from Dublin yesterday morning and, along with Johanne Devlin Trew and Kurt Taroff who are our colleagues in the Living Legacies Centre, I spent the afternoon with a group of around fifteen people who very generously shared their personal stories.

In my last post, I wrote about my planned visit to Enniskillen for the Northern Irish-leg of this workshop tour. I got the bus up from Dublin yesterday morning and, along with Johanne Devlin Trew and Kurt Taroff who are our colleagues in the Living Legacies Centre, I spent the afternoon with a group of around fifteen people who very generously shared their personal stories.

It was a really insightful, and at times emotional, workshop. I found it far more emotionally charged than any of the other workshops I’ve run. I think that’s because, as one audience member put it, talking about the First World War meant opening up another wound and many in Northern Ireland already have wounds, inflicted by the Troubles, with which to contend. I’m very grateful to those attending who spoke so openly and honestly, when, at times, it was obviously difficult for them to do so.

Creativity

As I mentioned in the last blog post, drama as a way into commemoration was going to feature in this workshop because of Johanne’s and Kurt’s areas of expertise. We were also joined on the day by members of the Omagh Writers’ Group and the Fermanagh Writers’ Group. They talked about how their creations that addressed the local experience of the War.

We heard about The Ghost of Christy Passed, a play created by eight authors. Set in October 1919, just before the first Armistice Day, family, friends and fellow soldiers give their accounts of how a young Catholic farmworker in Fermanagh came to be a the Somme. The creativity that produced this play was facilitated by the Living Legacies Centre, which had provided a safe space in which members of the Fermanagh Writers’ Group could develop their ideas.

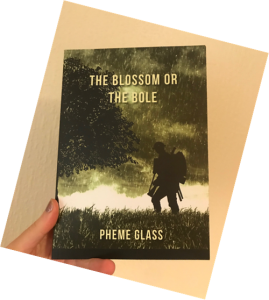

Pheme Glass very kindly brought me a copy of her novel, which tells the story of two young men and their deep bond, despite their different religious backgrounds. The Blossom or The Bole is a fictionalised reality, and, Pheme explained, it was very important to her to show the differences between what was happening locally during the war compared to the national scene.

Pheme Glass very kindly brought me a copy of her novel, which tells the story of two young men and their deep bond, despite their different religious backgrounds. The Blossom or The Bole is a fictionalised reality, and, Pheme explained, it was very important to her to show the differences between what was happening locally during the war compared to the national scene.

These novels and plays provided a creative outlet for people to think through the experience of war, both at home and on the front, and to consider the implications for family and friends. But, as we’ll see below, for one woman who turned to poetry, there was no comfort to be found in the act of writing.

What Have We Learned About Commemoration?

Speaking at the start of the workshop, Kurt explained that one of the purposes of the various Centres, now that we’re nearing our end, is to ask the question, What have we learned about commemoration?

This group in Enniskillen was divided in their opinions.

Some felt that commemoration was a burden of obligation and asked, ‘should we forget the past?’ If the generation who lived through the war did not want to speak about it, why should we dig and try to make sense of – perhaps even impose our understandings on – their experiences? Is it fair to ask future generations to carry these stories of pain? Does that not just transmit and perpetuate suffering, passing it onto the shoulders of those from whom relatives had tried to conceal it?

One contributor read from a deeply moving poem that she had composed about her grandmother. The opening line referenced four brothers who had died in the war. Her grandmother had never spoken about them so that she wouldn’t pass her suffering on. I asked if she had found the act of putting pen to paper, of thinking through her grandmother’s silence in this way, to be cathartic. But she explained how it had left her ‘disturbed’. Reflecting on such unspoken stories, another contributor likened commemoration to ‘a sense of mourning for a family member you never knew about’.

Others thought it necessary that the narrative is passed on. If our forebearers did not, or could not, talk about it at the time, given our remove, is it not our responsibility to give them a voice?

An interesting, and valid point, was made about the culture of the day – ‘people didn’t talk about things’. Are we now just assuming that the war was too painful to talk about, mis-interpreting a general tendency not to share?

There is no right or wrong answer to what are essentially very personal questions about remembrance. The workshop wasn’t about finding answers. That said, all present were in agreement that there needs to be guidance and official frameworks created so that those who grapple with their family legacies can be helped.

More in my next post.

Many thanks to Mark who brought along the medals of Pte Robert Byers, 9th Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, wounded in France in 1916.