Contributed by Julie Moore

Kensington Palace and Allotments

© IWM (Art.IWM ART 1127)

Sources to Consider and Questions to Ask

| The story of the impact of the First World War on farming is one which particularly benefits from research at the local level, revealing how even within a county or district, differences in soil condition, size of farm or patterns of cropping might see a difference in the responses towards issues around production, labour and farming’s place in the local community. We are keen to hear from those with such local knowledge and would invite you to help us build a more detailed and comprehensive picture of the ‘National’ Farm. Please contact us if you have a story you wish to share or a question you wish to put to a wider audience. |

Introduction

Farming played a crucial role in the war effort of all the combatant nations during the First World War; keeping the population fed, both military and civilian, was a key factor in maintaining not just physical strength but also morale and commitment to the war effort.

In 1914, Britain imported over 60% of its total food supply, and 80% of its wheat. Crucially, that imported food was consumed disproportionally by the poorer people. Four-fifths of wheat eaten in Britain came from abroad (only one loaf in five was made from British wheat), almost all of the sugar, four fifths of lard, three quarters of cheese, two thirds of the bacon and half of the condensed milk. British meat and fresh milk were expensive and more likely to be consumed by the wealthier classes. Cheap cuts of meat, brought in chilled from South America and Australasia were much cheaper than home raised meat but vulnerable to blockades and submarine attacks.

This reliance on imported food had been flagged up by farmers and landowners for many years as a justification for the protection of prices for home-produced goods. However, a policy of laissez-faire had seen the country, if not farmers, prosper, while confidence in the superiority of the Royal Navy to keep trade routes open and protect shipping had informed the policies of successive governments.

A long period of agricultural depression in the final decades of the 19th century, had seen many farmers switch into alternative crops, particularly dairy and beef cattle; these promised a higher return than arable crops such as wheat which were particularly vulnerable to overseas competition.

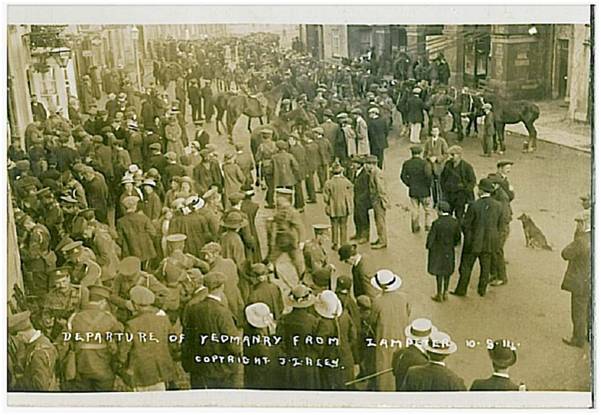

Farming is a long-term business so when war broke out, farmers did not see the need to change their cropping patterns. Calls from the government to switch to arable crops, ploughing up pasture to sow wheat for the daily bread, went largely unheeded; after all, if the war were a short one as was at first predicted, this would mean a large amount of work and outlay for little return, especially as arable crops were a very labour intensive investment at a time when men were leaving the fields to volunteer to fight.

The story of how farmers and government negotiated the conflicting demands of wartime is a fascinating and ultimately successful one; there were food shortages and problems but Britain, unlike Germany, never faced famine, and the farmers played their part in that. There are a number of sources which can help to track down the story of the impact of the war on farming in a particular locality. None is complete in itself, but each helps to build a more nuanced picture of how that story unfolded. As with all sources, survival into the 21st century is not guaranteed, and the detail or absence of detail given is often a result of the particular interests of those who compiled them, their passions and prejudices. Always bear in mind when considering any source- who produced it and why? What is missing and why? With those caveats in mind, here are some sources which may prove helpful.

Sources to Consider

Women, children and German Prisoners of War outside a barn in Suffolk (1918)

© IWM (Q 31044)

- Trade Directories, the 1911 Census, and the Inland Revenue ‘Domesday’ Books (1909-10)

The local trade directory is a good first step to identifying the farmers and smallholders in your area. This is a commercial directory so not all people are listed and the information can be slightly out of date, but they do offer a way of finding out details of who is living where. The 1911 census will give you more details of the farmer, his or her family and larger household. It will also give you a sense of just how many people within a locality depended on farming for their living. The Inland Revenue ‘Domesday’ Books and Maps offer a complementary source to the census. These were produced in anticipation of a new land tax which was due to be introduced by Lloyd George, but which never materialised as the war intervened. The maps are coloured to show different properties, whilst the books are organised on similar lines to the tithe maps and show details of landowners, occupiers, types of land or building (e.g. shop, arable field, farmhouse), rental values.These three sources offer a base line for any study of farming in the First World War and can be found at most County Record Offices or Archives, but check first with the individual office before travelling. Some trade directories are available free to access online The census is also available on a subscription basis from Find My Past or Ancestry . Check with your local library as some do offer free access to these digital services.

- County War Agricultural Committee Records

In 1915, with concerns around food supplies mounting and with a view to securing future harvests, the government called for counties to establish War Agricultural Committees. The records that survive give an insight into how concerns around farming changed as the war continued. These county committees in their turn set up district committees, comprising those with local knowledge, who, amongst other things, visited all the farms in their area and advised farmers on ways to improve productivity and which parts of their land they should turn over to arable production. Where the records survive, these give detailed descriptions of local farms and the correspondence they generated from farmers questioning the understanding or even goodwill of the committee members, and can give insights into a wide range of issues that farmers faced. Records also survive in some counties for Women’s War Agricultural Committees which were involved with the placement and welfare of the Women’s Land Army in their locality. These offer a fascinating glimpse into the concerns around women working on the land, both from farmers, the women of the committee and the women workers themselves.

Your first port of call for these records is your local County Record Office or Archive.

- Local Newspapers

Newspapers offer a fantastic range of material on all manner of issues affecting everyday life during the war, and give a great sense of change over time as well as being a way in to exploring a number of questions and assumptions that have survived into our own time. Do bear in mind that the newspaper business was driven by commercial considerations, so the selection of material included and the opinions they reflect may be coming from a very particular view of the world; in times of war the dissenting voice may be silenced or distorted. However, with that caveat in mind you can still find a lot of rich material on how the war impacted on everday life in general and farming in particular.

-

- Reports of the experiences of those who appeared before their Local Military Service Tribunal to appeal against their own conscription or that of an employee can give an idea of the sorts of issues that farmers faced; shortages of labour in general and skilled labour in particular were a common theme, as was the use of women, prisoners of war or conscientious objectors as replacements.

- Concerns around food hygiene and food adulteration could see farmers – particularly dairy farmers – summoned to appear before the magistrates to account for their procedures. The watering down of milk was a common complaint from consumers, and one that pre-dated the First World War period.

- Letters to the press from or about farmers can give an idea of the sorts of things that bothered people and how those concerns changed as the war progressed.

- Reports of the bringing in of the harvest can give an idea of how good or bad the harvest was, but also the kinds of celebrations which took place and the people involved.

- Away from farming specifically, food as a topic features very heavily in the newspapers and gives an idea of how people coped with shortages, queues, price rises. Advertisements show that some manufacturers and retailers were not slow to realise the potential for profit, whilst housewives were at the receiving end of a lot of rather patronising advice on how to avoid waste and make food stretch further.

Local newspapers (often on microfilm) can be found at your County Record Office or Archive and some branch libraries. The British Library also has a newspaper reading room but check with them first as you will need to apply for a Reader’s ticket and not all newspapers are available at present. The British Newspaper Archive is a subscription service which hosts digital copies of a large number of regional and local newspapers covering the years of the First World War. It is free to search online although you will need to subscribe to read the papers themselves., British Library members can access this service for free from the Reading Rooms of the British Library.

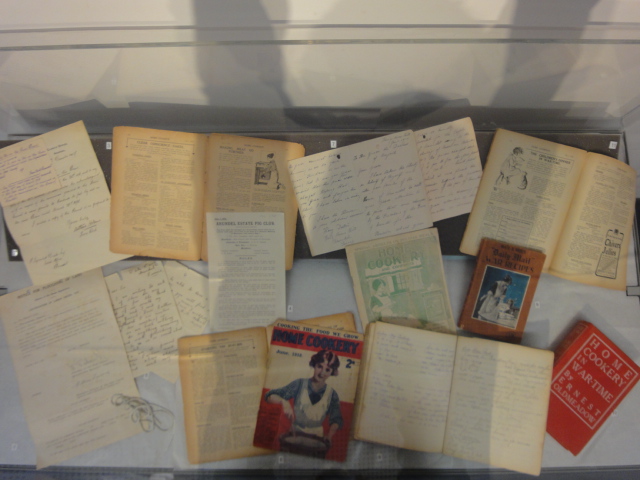

- Parish Magazines

Written for a very local readership, these can be full of detail on local people and local initiatives around keeping the parish fed. They often contain accounts of collections of food for Belgian refugees, convalescent or fighting soldiers, and families suffering hardship as well as accounts of parish celebrations, suggestions on how to avoid wasting food, or news of the opening up of new allotments to encourage people to grow more vegetables.

- School Log Books

The amount of information in these can vary considerably, depending on the level of detail thought necessary by the head teacher, but they can include details of children absent from school to take part in a variety of harvests – blackberries, potatoes, nuts – with the consent of parents and the authorities. Children in rural areas had always been likely to be absent from school for harvests, so looking back to what happened in the years before the war may give you a sense of where there is continuity and where there is change.

Parish magazines and school log books may be harder to track down. Some have been deposited with County Record Offices or Archives, but it may be worth speaking to your local school or church to see whether they have held on to theirs. In addition, Find My Past, have begun a programme of digitising admission registers and log books, and whilst coverage is not complete, the number is growing. You may only see the records up to and including 1914 at the moment to comply with a 100 year rule, but 1915 will become available to view in 2016 etc. To check their records go to Find My Past , select ‘Search records’, then ‘Education and Work’, in the box shown as ‘Record Set’ select ‘National School Admission Registers & Log-books 1874-1914’. You can then search by county, town or school name. This is a subscription service, but check with your local library or record office as those who are part of the project have free access for members.

A Reminder – always check with County Record Offices or Archives, Libraries or other holders of material before travelling. Sometimes there are gaps, and even when material does exist the staff may need notice to make it available for you to see.

Some questions to ask

- In spite of all the problems around food supply and farming, the people of Britain did not starve. What was the farmers’ contribution to this achievement?

- The ‘national’ farm contained diverse regions and cropping patterns. What are the particular influences that impacted on how your area responded to the challenge of keeping the population fed?

- Farmers saw their incomes rise by c.300% during the War as imports into the country were impacted by the disruption to trade routes. Is there any evidence of resentment from the wider public at this benefit from the war or is there more focus on their importance in keeping people fed?

- For much of the war those who worked on farms were treated favourably when it came to conscription into the armed forces as food was such an essential part of the war effort. Stories have been handed down of farmers ‘hiring’ their solicitor or accountant son to replace a ploughman who was let go and so no longer eligible for exemption from military service. Is there any evidence of this, or is this just the sort of story or myth that might enter the public consciousness in the wake of so many losses during the war and a sense that some sectors of society had had a better war than others? Many farmers did lose sons and other family members during the war so has that story been overlooked and if so, why?

- The use of women on the farms brought a number of issues to the fore and it is worth looking to see if or how these changed over time.

- Not all farmers were men. Farmer’s wives were not idle, often taking on specific areas of responsibility on the farm such as the making of cheese or rearing of poultry; widows ran farms to keep a tenancy going until a son was old enough to take over, and in areas where smallholdings were an important part of the rural economy, women and girls worked alongside their male family members to ensure the family’s income. How did the war impact on these women who were already an integral part of the farming economy?

- Rural women, especially those from agricultural labouring families, were well aware of how hard the work was and how it took place in all types of weathers. Where better paid alternatives were on offer were they more likely to take these ways of supplementing their income? Are those who are offering to work in the fields local women or from further afield?

- The repeated assumption was that women were not up to the physical demands of farm labour. In addition the Victorian and Edwardian rhetoric was of farm work as unfeminine. Is there any sense of this rhetoric being re-written for the period of the war or was it more robust than that?

- Farmers were also reluctant to take on women as made it less likely any appeals to tribunals to prevent men being conscripted after 1916 would be accepted if they could show an alternative labour supply. Is there a sense that farmers soften in their attitudes or is the male prisoner of war seen as a better alternative?

- Beyond the formal farming set up, there was a push to increase food supplies by encouraging the setting aside of land for allotments, including the turning over of flower beds in municipal parks to the growing of vegetables. These initiatives varied widely across the country and were often dependent on a few committed people. What was happening in your area and how successful were the campaigns to get people growing more vegetables? What sorts of restrictions were there on what people might grow and did this reflect concerns from smallholders and others around competition?

There are more questions than answers surrounding the whole area of farming during the First World War, and some questions will be more relevant than others for different parts of the country. In seeking to find answers to these we hope to develop a more detailed picture of the rural experience during the war and perhaps find new questions to pursue.

Suggested reading

Maggie Andrews & Janis Lomas, The Home Front in Britain (2014) Palgrave Macmillan

Peter Dewey, British Agriculture in the First World War (1989, new edition 2014) Routledge

Bonnie White, The Women’s Land Army in First World War Britain (2014) Palgrave Macmillan