Contributed by Julie Moore

Recently, whilst reading through the correspondence of Samuel Graveson, clerk to the Hertford and Hitchin Monthly Meeting of the Society of Friends, it struck me that there is more research to be done at the local level on the relationship between those conscientious objectors who found work on farms, and the farmers who hired them.[1] Men willing to take on agricultural work tend to be less visible within the story of war resistance than their fellow objectors who took an absolutist stance, but their experiences can throw light on attitudes to the war at the local level.

This is very much work in progress, but one immediate question is the practical issue of how clerks, shopkeepers and plumbers found their way from the town to the countryside. From the letters of those who contacted Graveson in 1916, it seems that men made their own arrangements in those first months of conscription. What emerges from the surviving postcards and letters was the fairly rapid development of a word-of-mouth network which gave Quakers access to sympathetic farmers.

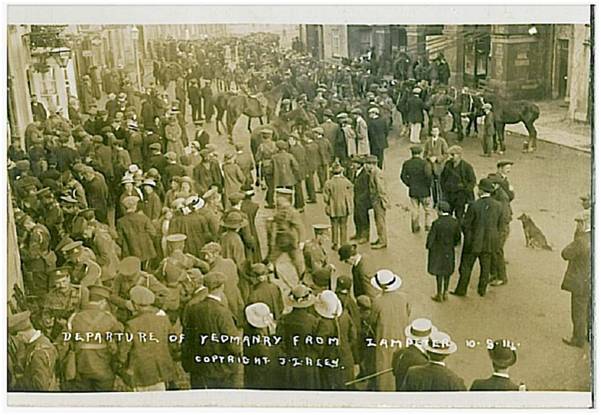

‘The result of Military Service Tribunals sending conscientious objectors to work on farms’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 29th May 1916, p.3.

Newspaper images (c) The British Library Board. All rights reserved.

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Samuel Graveson supported a number of Quakers in their applications for exemption, and his name was passed on to others as somebody worth contacting. In July 1916 he received a letter from a St. Albans draper, Ernest Hickling, who wrote that the Tribunal had ‘let me off very lightly’ with an exemption from combatant service conditional on joining the Friends Ambulance Unit. However, he was concerned about a fellow applicant, Oswald Godman, a postman, who needed to find farm work within the next 28 days as a condition of his exemption. Hickling had heard that there was a ‘gentleman out Hitchin way, wanted some men for his farm’. He didn’t know the name, but he understood the farmer was a ‘Friend’.[2] Could Graveson help put Godman in touch?

A copy of Graveson’s letter does not survive, but the archive has a note from Thomas Howitt, who had previously employed conscientious objectors recommended by Graveson on his fruit farm at Holwellbury, near Hitchin; the farm was one owned by the prominent Primitive Methodist, William P. Hartley of Hartley’s Jams fame.[3] Howitt, a Quaker, replied that he was unable to take on any more men at present, but he gave Graveson details of a fellow fruit farmer near Dunstable who should be able to help.[4]

Howitt himself was later called before the Ampthill Military Service Tribunal where he was granted an exemption from combatant service on grounds of conscience.[5] Cyril Pearce’s database reveals that whilst the tribunal allowed Howitt to take on agricultural work, it insisted that he should not serve out the war on his own farm. He was given permission to supervise the autumn harvest, but returned to his new employer, J.E. Matthews of Letchworth, yet another farming Quaker, once the fruit had been collected.[6]

Clearly the Society of Friends adapted its networks to the needs of conscientious objectors. Research at the local level may reveal more of how that worked in practice. Was there parity of earnings for those working on the farm? Where did the men lodge? In an earlier letter, Howitt mentioned he was unable to offer accommodation on the farm but was confident that the local neighbourhood could provide, which raises questions of how the men were received locally.[7] How did those who were not Quakers manage to access farms, and was there a difference in approach between Quaker and non-Quaker farmers to the employment of conscientious objectors?

Lots of questions, and looking forward to finding some answers.

[1] ‘Correspondence and other papers relating to Conscientious Objectors 1916’, Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies (HALS), NQ2 11A/2

[2] Letter from Ernest Hickling to S. Graveson, dated 11th July 1916, HALS NQ2 11A/2/103

[3] Sir William Pickles Hartley’, http://www.myprimitivemethodists.org.uk/page_id__714.aspx accessed 8th August 2016.

[4] Memo from T.H. Howitt to Graveson NQ2 11A/2/103, August 1916. The memo is on headed notepaper W.P. Hartley, Postal Address Howellbury Fruit Farm, Hitchin. Head Office & Works Aintree, Liverpool, Southwark, London.

[5] ‘Sir William Hartley’s Farm Employees’, Biggleswade Chronicle, 26th January 1917, p.4.

[6] ‘Thomas Henry Howitt’, Conscientious Objectors Register 1914-1918, https://search.livesofthefirstworldwar.org/record?id=gbm%2fconsobj%2f8900 accessed 8th August 2016.

[7] Letter from T.H. Howitt to S. Graveson, NQ2 11A/2/45, 25th March 1916

Originally posted on the 15th August, 2016