Theatre and Entertainment During the First World War

Contributed by Andrew Maunder

It is difficult to ignore the hold which theatrical entertainment had on the public in the war years. There were plenty of obstacles to theatre’s success: a lack of young male actors, blackouts, Zeppelin raids, unreliable public transport and, after 1916, an Entertainment Tax which prompted a rise in ticket prices. But apart from closure in the feverish months of August – September 1914, by the end of the year newspapers and magazines were commenting about how crowded theatres and music halls were. Some people thought going to theatres was in bad taste given the events in France and Belgium but others viewed such self-denial as unnecessary. Frivolity as usual?’ asked The Bystander, `and why not? Those of us who stay behind would do a sorry service to our country by moping all day and all night…The love of fun is eternal and it will take a bigger beast than the Prussian to bully us out of it.’

Plays with a Purpose

Although it was not a reserved occupation, theatre was often seen to have an important national role: it was therapeutic and escapist. It was also a channel for propaganda. Suitable old plays were revived – Shakespeare’s Henry V or Louis Parker’s Drake– but hundreds of new ones were written, most of them very topical. Many had very evocative titles: The Beast of Berlin (1914), The Supreme Sacrifice (1914), The Master Hun (1915), The Day before the Day (1915), The Peril in Our Midst (1915), Somewhere a Heart is Breaking (1916), The Iron Hand (1916), The Wages of Hell (1916), Out of Hell (1917), For My Country (1917), The Hidden Hand (1918), The Female Hun (1918). These plays can seem simplistic. They tend to follow recognizable pattern: a struggle between good and evil, constructed aroundesd ordinary men or women, coping with highly- pressurized, topical situations – the threat of German invasion, spies or the `enemy within’ – whilst showing solid `English’ values emerging triumphant.

Black `Ell

Some playwrights did question the war and their work tends to fit more neatly with the attitudes which emerged afterwards in the 1920s and 1930s. Miles Malleson’s Black ‘Ell (1916) is one example. It is about a decorated young man, Harold Gould, who is haunted by his killing of a German soldier and questions the whole idea of self-defence’ upon which the war is said to have been launched. Harold’s well-meaning family don’t understand and the play stresses the distance between those who have seen and those who haven’t. However this play was never performed during the war. Until 1967 every stage play had to receive a performance license from the Lord Chamberlain’s office (it was refused). The play’s subsequent banning under the Defence of Realm Act (D.O.R.A) was typical of the war-time government’s nervousness about descriptions of trench war on stage but also its recognition of the power of theatre itself. We might ask about the other plays that failed to get a theatrical license. Why?

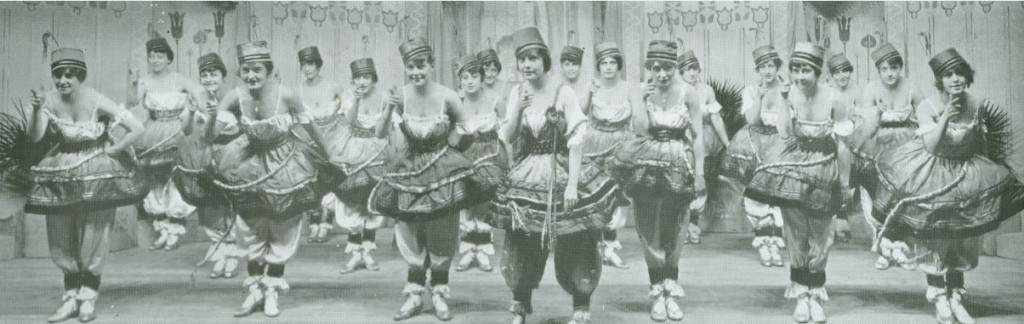

Revue

Historians of war-time culture have continued to maintain a fairly disparaging stance in regard to this popular sub-speciality of topical sketches, music and chorus lines: Shell Out! (1915), Now’s the Time (1915), Bubbly (1916), Buzz Buzz (1917).

The jokes have perhaps lost their bite but it’s the disposable songs which stand out when we first look at the script of a show like the Charles Cochran-produced Pell Mell (1916) which ran for 300 performances at London’s Ambassadors theatre: `I’m a musical comedy bus’ness man’, `The Jabberab-jee’, `You’ve got to do it’, `I’d like to know what Cleopatra did’, `Never let your right hand know what your left hand’s going to do’, `The right place for meeting is the Piccadilly tube.’ Not everyone approved. In 1916 General Sir Horace Smith Dorrien made a much-publicised complaint about the stage’s `indecent and suggestive unnecessaries’ and the demoralizing effects `scantily dressed girls and songs of doubtful character’ were having on `our young officers and soldiers.’ Some theatre managers sued for libel.

Gaby Deslys

Despite the celebrity of people like Marie Lloyd and Harry Lauder, the biggest draw – at least in London – was Gaby Deslys (1881-1920). In 1915 the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News had no doubt that `Mlle Deslys is a very queen of players. Women shriek wildly with joy, and strong men break down and gasp, at the glory of it.’ The air of scandal surrounding Deslys intrigued audiences; she was a former mistress of King Manuel II of Portugal and others. As well as wanting to know what she ate for breakfast and what face cream she wore, people wanted to see the exotically costumed Frenchwoman in the flesh, as well as needing to know whether she could actually dance (she could) and sing (less well). Deslys was at the top of the theatrical tree. But what about those who were further down? What did they do?

Legacies

Recovering the forgotten plays and personalities of the war-time theatre industry is a way of finding out about a largely unknown dimension of war-time cultural life. It can seem a challenge because texts are not easily availably but also because nowadays First World War drama tends to be represented by Journey’s End (1928) and Oh What a Lovely War (1963).These are indisputably powerful pieces but there is something a bit odd about the way they’ve come to stand in for First World War drama as a whole. They’re both post-war pieces written after the events with the benefit of hindsight.

Working with us

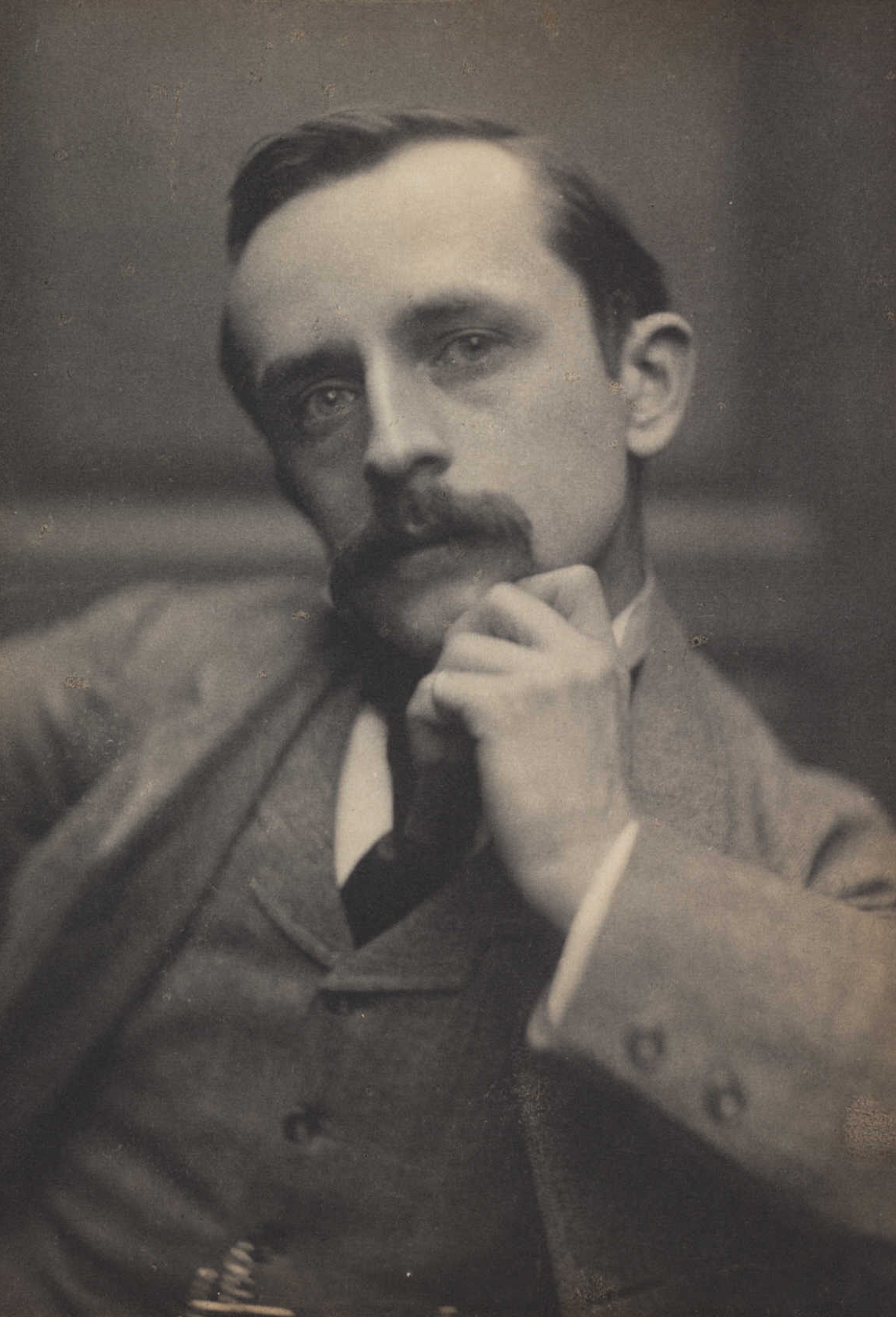

One aspect of our work with war-time theatrical material involves reintroducing something of the experience of war-time plays to modern audiences via revivals. Our most recent production as J.M. Barrie’s spiritualist drama A Well Remembered Voice (1918).

We’re keen to work with people interested in developing this material – reviving one of the plays themselves – or who are creative writers working on their own piece about the war. Or perhaps one of your ancestors was involved in the theatre industry during the war? We’d be interested in hearing about them. Alternatively, maybe one of the theatres in your town played an important role during the war and you’d like to do some work on that.

Further Reading

L.J. Collins. Theatre at War 1914-18. London: Macmillan, 1998; rev ed. Oldham, Jade Publishing, 2004.

Sos Eltis. Acts of Desire: Women and Sex on Stage, 1800-1930. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013

J.G. Fuller. Troop Morale and Popular Culture 1914-1918. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Michael Hammond and Michael Williams, eds. British Silent Cinema and the Great War. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Heinz Kosok. The Theatre of War. The First World War in British and Irish Drama. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2007.

Jerry White. Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War. London: The Bodley Head, 2014.

Gordon Williams. British Theatre in the Great War: a Re-evaluation. London: Continuum, 2003.