Contributed by Nick Mansfield

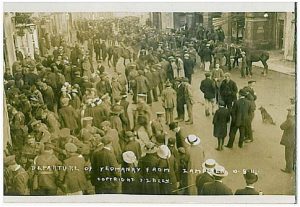

The mobilisation of the Welsh Horse Yeomanry at Lampeter in west Wales, in August 1914. The Yeomanry found it difficult to recruit further volunteers.

One hundred years ago, the British government for the first time introduced conscription for compulsory service in the armed forces; a response to the high battlefield casualties and the need for mass mobilisation to defeat Germany. Exemptions were granted both on conscientious grounds, or for reasons of urgent and vital work for the national interest. Such appeals were heard by local Military Service Tribunals. One of the most unusual of these was heard in Shropshire when, in 1916, the South Shropshire Hunt applied for exemption from conscription for their kennelman, one of their full time and professional hunt servants. At a time when the bloody battle of the Somme was at its height, what might have been thought of as a frivolous and unworthy appeal, was agreed in full by the tribunal. Its chairman declared: ‘the military had no objection at all to the application. It was a recognised that hunting should be kept up’. Such was the power of the vested rural interest of foxhunting and its military wing of the county Yeomanry.

The later were originally formed from local foxhunting packs around 1800, as part-time mounted home defence force to oppose Napoleonic invasion. They were socially exclusive; mainly farmers’ sons, officered by the county gentry. After 1815 the Yeomanry continued as a para-military gendarmerie used to act against a wide range of early nineteenth century protestors. Their methods were often violent, with Manchester’s Peterloo Massacre only one example of their handiwork. The Yeomanry were also very political and overwhelmingly supported conservatism. Their policing role if the countryside was superseded by the new county constabularies, but the Yeomanry continued their existence as old fashioned military auxiliary units, still built around fox hunting and the associated, and often raucous, social and political activities.

On the outbreak of war in 1914 the Yeomanry were immediately caught up in the military rhetoric in which sense of place, and the importance of the county was stressed. Although most voluntary recruiting was concentrated on the rural Kitchener battalions of the county infantry regiments (it was these that mainly absorbed the 200,000 farmworkers who volunteered), Yeomanry regiments were also increased. Social exclusivity continued as Yeomanry preferred ‘farmers sons…every man had to supply his own horse…they considered themselves a cut above the normal infantry regiments like the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry’ particularly as ‘enormous numbers of rank and file, being officer material, were commissioned in the early years of 1914-1918.’ Siegfried Sasson (who had served in the ranks of the Sussex Yeomanry) was the archetype of these gentleman rankers who officered the mass armies, and his memoirs form a good account of this process.

The world of foxhunting was also part of this military rhetoric: ‘There has been prompt and loyal response from the Hunts both with horses and men…of the 10,000 or more hunting men with the colours we need not write, for they shall do and they shall dare, as becomes their blood and breeding. A great number of Masters were already officers in the Yeomanry of Territoral Forces. The masters lead… with a tale of over 80% of their number, the Hunt Secretaries following with over 50%, while the Hunt Servants with over 30%.’ Recruitment techniques made specific reference to the historic military prowess of particular counties. So, Shropshire men were characterised as ‘proud Salopians, bulwark against the Welsh’, as one Yeoman said, ‘Shropshire border people were always very wary of Welsh people you know…we didn’t trust them somehow…there was something underhand about them’. Yet there was a sense in the farming part of the Yeomanry/foxhunting community that this rhetoric did not apply to them.

In addition, the Yeomanry’s amateurism was still apparent. One sergeant serving in a newly mobilised Yeomanry brigade recalled:

I was unlucky enough to appointed NCO in charge of the guard on the main gate, with strict orders not to allow anyone through without a special pass…a mighty roar broke out from the Cheshire Yeomanry lines, followed by a rush of troops for the main gate. We tried to bar their way, but were powerless …the Denbighs began to follow…’’What is the trouble?’’ I asked. It was the grub they said. They were going to Chester for a decent feed.

There was no legal requirement for the Yeomen to serve abroad and although the majority did volunteer, there was an accommodation with the military authorities who allowed some Yeomen to carry on farming whilst serving at home. A Shropshire yeoman interviewed in the 1970s claimed ‘the half of the Yeomanry that were grass farming could go home for the hay harvest and the arable yeomen could go home for the corn harvest’. This was formalised as the Yeomanry regiments were ordered to raise a second line unit to act as a reserve and to accommodate the sizeable minority who choose not to volunteer for overseas service. One eager subaltern in the home service unit of the North Somersets wrote: ‘the life is ghastly. No training only odd jobs and standing about amongst half dressed farmers who’ve refused to go abroad and only want to get back to their farms’. Another regular officer complained: ‘they [were] always going home for a bit and turning up again. I heard the other day of a unit where 79 disappeared one night without leave – They turned up again in 3 days to a fortnight, quite calmly saying that they had been home to do a bit of work on the farm and seemed to think it quite natural.’

After the initial enthusiasm and the departure of the first line Yeomanry, it soon became clear that their natural rank and file constituents – the farmers and their families that remained – perhaps prompted by labour shortages, were not inclined to volunteer. The failed appeal in January 1915 of Lord Kenyon commander of the 2nd Welsh Horse for volunteers is typical:

Rightly or wrongly it has been said that recruiting has not been as active as in other parts of the country and more especially has this been said of the farming class, the mainstay of my regiment.

Typical of newer recruits, Charlie Crouch, a railway shunter from Cambridge, volunteered for the gentlemen’s club of the 2nd Suffolk Hussars (Yeomanry) in 1915.

As the war continued this became part of the general opinion that farmers were shirking and doing well from the hostilities. The solution was to recruit from further down the social structure. So the Wiltshire Yeomanry took in ‘railway trainees, local teachers, clerks, shop assistants … who had never ridden a horse. The feeling was it was going to be a jolly sporting show and that we’d see some fun with the Yeomanry’. Even working class men began to be accepted, like my uncle Charlie Crouch, a railway shunter from the east end of Cambridge, who sneaked into the Suffolk Hussars despite never having ridden a horse in his life.

Some Yeomanry regiments served bravely abroad. In the Leicestershire Yeomanry – crack hunters of the Quorn and Belvoir – 94 per cent volunteered for general service as did 85 per cent of the Gloucestershire Yeomanry, veterans of the Berkeley and Beaufort Hunts. Parted with their horses temporarily at Gallipoli they had the difficult task of defending the same length of trench as a full infantry battalion. They were re-mounted for full scale cavalry operations in Palestine, where the Duke of Beaufort’s whipper-in won the Military Medal with the Gloucestershire Hussars. As casualties mounted and horses seen to be irrelevant to the slaughter on the Western Front, other Yeomanry regiments were converted to infantry. Despite vehement protests, a few had the ultimate indignity of being converted to cyclist battalions. They retained what they called the ‘Yeomanry spirit’, their cavalry uniforms (illegally) and an interest in hunting. A pack from the Quorn was hunted behind the lines in France by the Leicestershire Yeomanry, hounds were taken to the Salonika front by Scottish Yeomanry, and to Egypt by the Hertfordshire Yeomanry. (As late as the Second World War, some yeomanry regiments were allowed to take their fox hounds and horses to the Middle East, where they hunted jackals in Lebanon.)

In Britain hunting continued throughout the First War, even after rationing had been introduced. In the Albrighton Hunt, in Shropshire, Mrs Mayall, wife of Major C.G. Mayall took over as Master of Foxhounds, ‘During his absence in the Dardenelles.’ However overall shortage of labour caused difficulties:

‘Another source of trouble was that no wire was removed and that this very often allowed of hounds getting clean away from their attendants. Again there was the stopping [foxes’ earths] difficulty. Like the hunt servants, all the younger gamekeepers were serving, and the veterans who took their places were not probably very keen on turning out at night’. In the autumn of 1916, whilst stationed at Huntingdon, the commander of the Hertfordshire Yeomanry defied Government orders that regimental horses should not be used to follow hounds: ‘The officers … managed to get a lot of hunting with the Cambridgeshire and Fitzwilliam.’

Against this background the exemption from military service for their staff was raised by the hunts. After the South Shropshire got their kennelman exempted, other hunts followed, with the military authorities agreeing a general exemption in counties ranging from Norfolk, to Northamptonshire to Northumberland. It was widely felt that the price was worthy paying for the morale-raising effect hunting could give officers on leave or convalescent. Siegfried Sassoon’s memoirs give an indication not only of this process but also the way it became an absent representation for ‘Englishness’ and all that they were fighting for at the front. Country Life reflected the same sentiments: ‘How many of them writing from the front, have referred to the sport they love, and have expressed the wish that they may find it going strong when they return…leave barbed wire for its fit use – to protect war trenches and trip up enemies, not friends, nor gallant lads who are fighting and dying for our homes and country, the home of the finest sport on earth.’

Such sentiments were probably not shared by the rural infantrymen (mainly farmworkers) ordered over the top, following the attacking strategy of Douglas Haig – cavalryman and foxhunter, in which they sustained enormous losses. The same month that the South Shropshire Hunt secured deferment for their hunt servant, Lord Hastings, was promoted to be commander of the 2nd Norfolk Yeomanry, despite having refused to go on foreign service and despite much criticism, which included Parliamentary questions, the appointment was confirmed. By this stage in the war, some farmers were sacking their workers and moving their sons into their places, allowing the former to be conscripted. All of this contributed to class conflict and a wave of protest from farmworkers’ unions, ex-service organisations and the newly formed rural Labour Party.

After the Armistice, the Yeomanry had a problem in recruiting in the face of anti-war feeling, compounded by the temporary success of this rural radicalism. However, in most of rural Britain, the elite rapidly recovered their political hegemony by establishing new paternalistic institutions like village halls, Women’s Institutes, the British Legion, war memorials, and Young Farmers Clubs. These had the purpose of genuinely wishing to improve the quality of rural life and deflecting rural depopulation. Older institutions like foxhunting and the Yeomanry, seeming to symbolise the national unity of 1914 and local county pride also played a part in this self-conscious post-war reconstruction. The Yeomanry though, could still play a policing role as in 1921, when the Yeomanry were indirectly called in again ‘to assist in the preservation of civil order’ during the national coal strike. In Shrewsbury, Master of Fox Hounds, Colonel H.H.Heywood-Lonsdale, raised the Shropshire Dragoons from Yeomanry volunteers. Although they did not see any action, five years later many of their members served as volunteers during the General Strike.

Nick Mansfield, Senior Research Fellow in History at UCLan.

For further reading see the author’s

English Farmworkers and Local Patriotism, 1900-1930, (Aldershot: Ashgate Press, 2001)

‘Foxhunting and the Yeomanry – county identity and military culture’, in R.W.Hoyle Our Hunting Fathers: field sports in England after 1850, (Lancaster: Carnegie 2007)

‘The Yeomanry: Britain’s 19th-century Paramilitaries’, History Today, August 2013, Volume 63, 8.