In this account, Andrew Maunder, who is researching actors and music-hall performers who served in the forces, describes some of the issues which have emerged over the course of his enquiries. He would be pleased to hear from anyone working on a similar topic. A.C.Maunder@herts.ac.uk

The field of historical study on actors and the First World War has traditionally focused mainly on their roles as entertainers (often for the troops), fund-raisers (charity concerts) and sometimes as recruiters (making patriotic speeches from the front of the stage). This brought them a good deal of praise. In 1918, King George V praised “the handsome way in which a popular entertainment industry has helped the war with great sums of money, untiring service, and many sad sacrifices.”

King George’s last phrase (“sad sacrifices”) is a reminder that another way of thinking about the activities of actors, and also music hall performers, is to consider their roles as combatants. Despite a tendency on the part of the popular press – The Weekly Despatch, is a case in point – to see actors as shirkers, or “evasionists”, the evidence suggests that large numbers served in all three branches of the armed forces between 1914 and 1919. Many actors were volunteers and enlisted in autumn 1914. Some had served in the army previously or were already in the territorials. These early recruits were feted in the press – particularly in trade papers favourably-disposed towards them: The Era, The Stage and The Performer (the latter dealing largely with music hall and variety business). 100 years later, these same papers are a very useful starting point for discovering more about the men who saw active service. They list the names of those enlisted under the heading “The Profession with the Colours.” They are also punctilious in recording who had been wounded, decorated or killed. They also feature letters from army bases and convalescent homes in which the actor-soldier asks not to be forgotten by the profession.

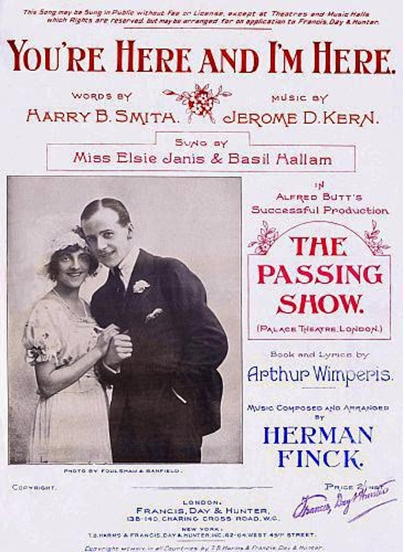

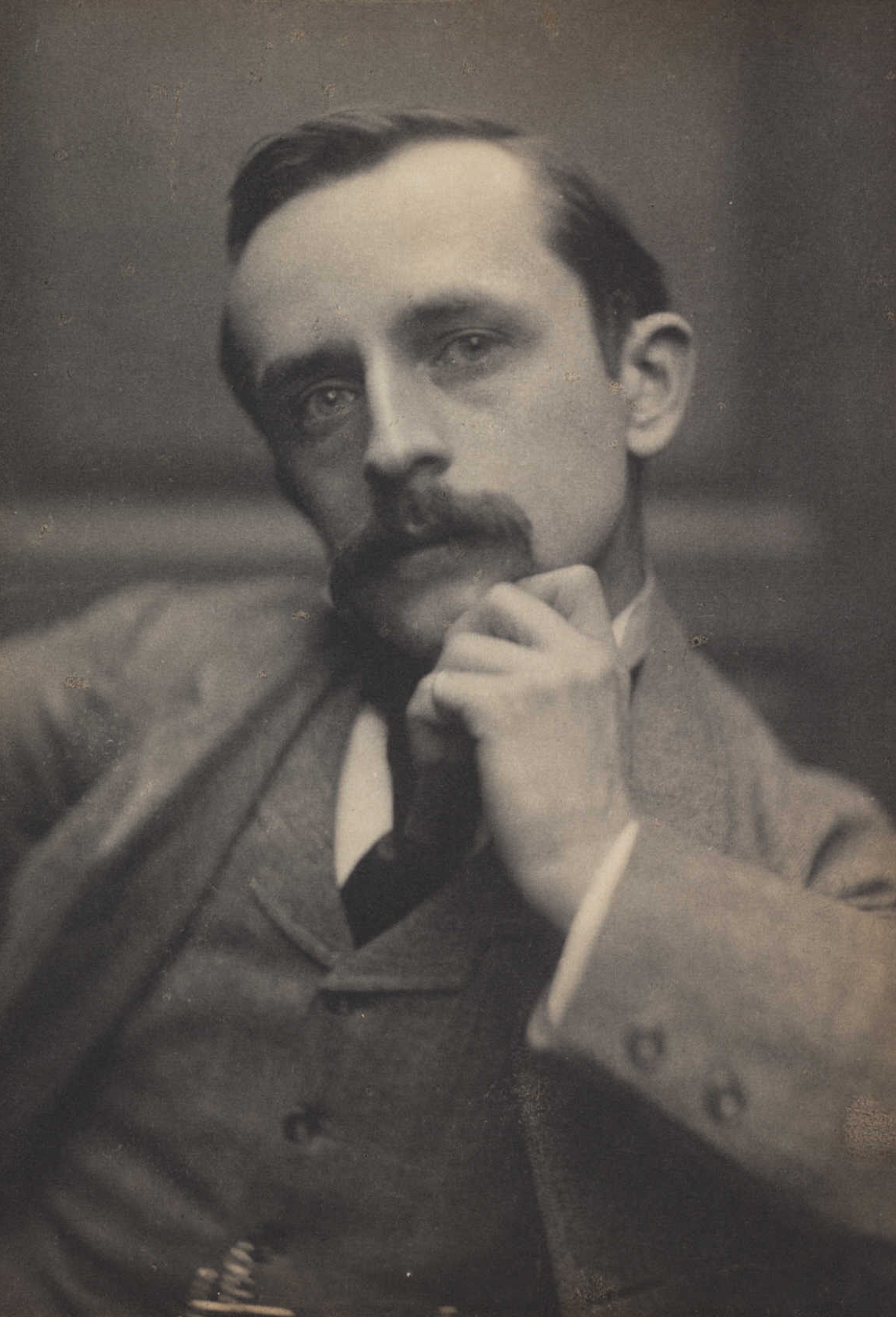

Not surprisingly, it is easiest to find out about well-known actors. They received most press attention, gave interviews and had their photos taken (see the photo [above] from The Sketch 26 July 1916). Basil Hallam Radford (1889-1916), Lionel Mackinder (1869-1915), remembered recently by his old school, Donald Calthrop (1888-1940), and Robert Lorraine DSO (1876-1935; already a celebrated aviator as well as actor before the war) are notable examples. Others who would become famous after the war – Basil Rathbone, Cedric Hardwicke, Leslie Howard, Arnold Ridley – also left us reminiscences about their war service or their biographers told their stories.

Most of this (middle-class) group gained commissions. The suitability of actors as officers was regularly commented on by the trade press. “As for the stage or variety performer in the higher walks of the profession it is generally admitted by those best qualified to judge that he makes a very good officer: intelligence, confidence, self-command, and good physique are all more or less found in the equipment of a successful performer” (“Do Stage Folk Make Good soldiers?”, Performer, 6 August 1917 p. 17). Despite their dubious profession, these men at least knew how to act in a gentlemanly way; those who were public-school educated knew what was expected anyway.

Basil Hallam

One way of discussing the topic has been to take individuals as case studies. An instance of this is Basil Hallam, a fashionable variety performer known for the character of “Gilbert the Filbert” in a West End revue, The Passing Show of 1915. In 1915, Hallam joined the Royal Flying Corps as a balloon observer. His job was to take photos for mapping where enemy shell and gunfire were concentrated and to plot trench positions. Before joining up he had been in the receiving end of abusive letters and white feathers. His service records held in the National Archives (WO 339/58073) note a physical disability (a hammer toe) which required a specially-adapted shoe. The records also record a swift awarding of a commission (he had been educated at Charterhouse School). To the public, who followed his career via gossip columns he now fitted the popular ideal of expected masculine behaviour.

This was compounded by Hallam’s apparently heroic and public – death. The circumstances were horrific and many people left writings about it. When his balloon broke free from its moorings and started to drift towards enemy lines, Hallam threw the camera equipment and maps over the side, gave the balloon’s 2 parachutes to the 2 other men in the basket and then jumped out himself, plunging 6,000 feet – “like a stone”, according to Dundee Courier (“How Basil Hallam Met His Death, 4 September 1916). Philip Zeigler’s Diana Cooper: The Biography of Lady Diana Cooper (1982) quotes Raymond Asquith’s eye-witness letter to Hallam’s ertswhile girlfriend, reporting that Hallam’s body was found “dreadfully foreshortened”; his cigarette case was the only identifying mark. Rudyard Kipling also describes Hallam’s death in The Irish Guards in the Great War (1916), although the details of his version are slightly different [link]

Because he was an actor who was well-known and well- watched Hallam’s story is easier to track than many contemporaries. There is even a Times obituary (24 August 1916). Other newspapers carried photos of his grave at Couin British Cemetery. Since then these events have also been deployed – and hence written about – as an example of J.B. Priestly’s “great [lost] generation, marvellous in its promise” (Margin Released, p.213).

Unsurprisingly, it’s more difficult to reconstruct the service careers of performers who weren’t “stars”, whose enlistment, return or death went largely unrecorded. The National Archives hold Army Service Records online but one particularly challenging aspect is discovering the “real” names of some of these men. Performers use stage names. Away from the stage and the theatrical newspapers, many disappear, even those who were well-known at the time.

Conscription

In autumn 1915, other performers attested under Lord Derby’s Scheme i.e. they signalled their willingness to serve should they be called upon. This willingness was often inserted in theatre programmes lest the audience should be in any doubt as to the patriotism of those involved. However, the audience often was in doubt. There are plenty stories of actors being harangued from the auditorium.

One frequently-made point was that many performers looked younger than they actually were. In 1917, Fred Russell, Chairman of the Variety Artistes Federation, explained that 80% of male stars “are over military age” and that “appearances are deceptive. The entertainer who passes for twenty-five from the front may be a grandfather. It is part of his business to preserve a youthful appearance, and `make-up’ goes a long way in that direction” (“Pros and Patriotism”, Performer 28 June 1917, p.17).

After the Military Service Act (1916) it was very difficult for a professional actor or entertainer not to have to do some kind of national service. This was particularly so autumn 1916-17 when conscription began to be more ruthlessly enforced. Local police regularly turned up at theatres to check actors’ papers, not least because it was feared that the itinerent lifestyle of the professional performer (i.e. moving from town to town on tour each week) made it possible for him to slip the net.

The Military Service Act did, however, allow for some exemptions. If the 19 records of the Middlesex Appeals Tribunal held at the National Archives featuring actors are typical, the majority tried to refuse national service on economic grounds (i.e. they had family dependent on them). This was followed by ill-health. Indeed, a surprising proportion cite health issues – so much so that we might wonder (like the tribunal members) how they ever climbed up on stage. The Middlesex Tribunal tended to be unsympathetic, even with doctor’s reports proffered as evidence. They rarely granted exceptions. One concession they did make was to allow actors to finish a current engagement before being required to report for duty.

Conscientious Objection

The Middlesex records show that despite popular belief about actorly cowardice only 1 actor declared himself a conscientious objector. Case M199 Theodore Edwin Greenwood, aged 20, living in Chiswick, claimed to be willing to help people in distress “but I cannot accept organised relief work, which entails any sort of compulsory cooperation with the State.” His appeal was dismissed on 27 March 1916. Frustratingly Greenwood then disappears. There is no military service record but he was presumably required to do some kind of national service. Performing would have been largely closed to him. Without exemption papers very few theatre managements would have employed him. This was doubly so after March 1918 when an amendment to the Defence of the Realm Act made managements liable for prosecution.

Memorials

Like other professions, another way of finding out about the actors who fought comes via memorials.

John Frearson has written about the plaque erected to 12 members of the actors’ club, The Green Room who were killed (see The Green Room Plaque; 2014).

Sylvia Morris has researched the 1914-1918 War memorial window [http://theshakespeareblog.com/2012/09/stratfords-band-of-brothers-the-bensonian-company/], erected in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1925. This is dedicated to actors who worked with actor-manager Sir Frank Benson and his Shakespearean company.

London’s Drury Lane Theatre also has a large memorial. Sadly, another put up outside the stage door of London’s “Old Vic” in 1918, was destroyed in the blitz in the subsequent war.

There may be more.

Suggested Resources:

The Stage

The Era

The Performer

The Sketch

The Weekly Dispatch

The Stage Yearbook

National Archives First World War Records https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/first-world-war/