Contributed by Andrew Maunder

As the Finborough Theatre in London stages a new production of St John Ervine’s 1913 powerful suffrage play Jane Clegg, it’s worth thinking more about the play’s Ulster-born author (1882-1971). He was a very familiar personality in the 1920s and 1930s, thanks to his plays, newspaper columns and radio broadcasts but nowadays he is hardly known.

Ervine had close links to Hertfordshire thanks to his friendship with George Bernard Shaw, who lived in the New Rectory at Ayot St. Lawrence, a house now owned by the National Trust. He was a close friend, too, of Frederic Osborn (1885–1978) a member of the UK Garden city movement and one of the founders of Welwyn Garden City.

When Ervine, one of about 210,000 Irishmen to serve in the British forces during World War I, made the unexpected decision to enlist in 1916 it was to Shaw that he wrote about his experiences. This is Trooper Ervine describing on 17 November his initial impressions of training camp with the Household Battalion in Windsor:

“I think I’ve learnt more about the British people in the past month than in the whole of my previous fifteen years residence in London….At first I thought they [the men in the regiment] endured things because they were too stupid not to endure them; but, knowing them better, I’ve discovered that they’ve got a philosophic basis for their cheeriness. One of them said to me lately ‘if you take it hard, you might as well commit suicide’; so they all make the best of it.”

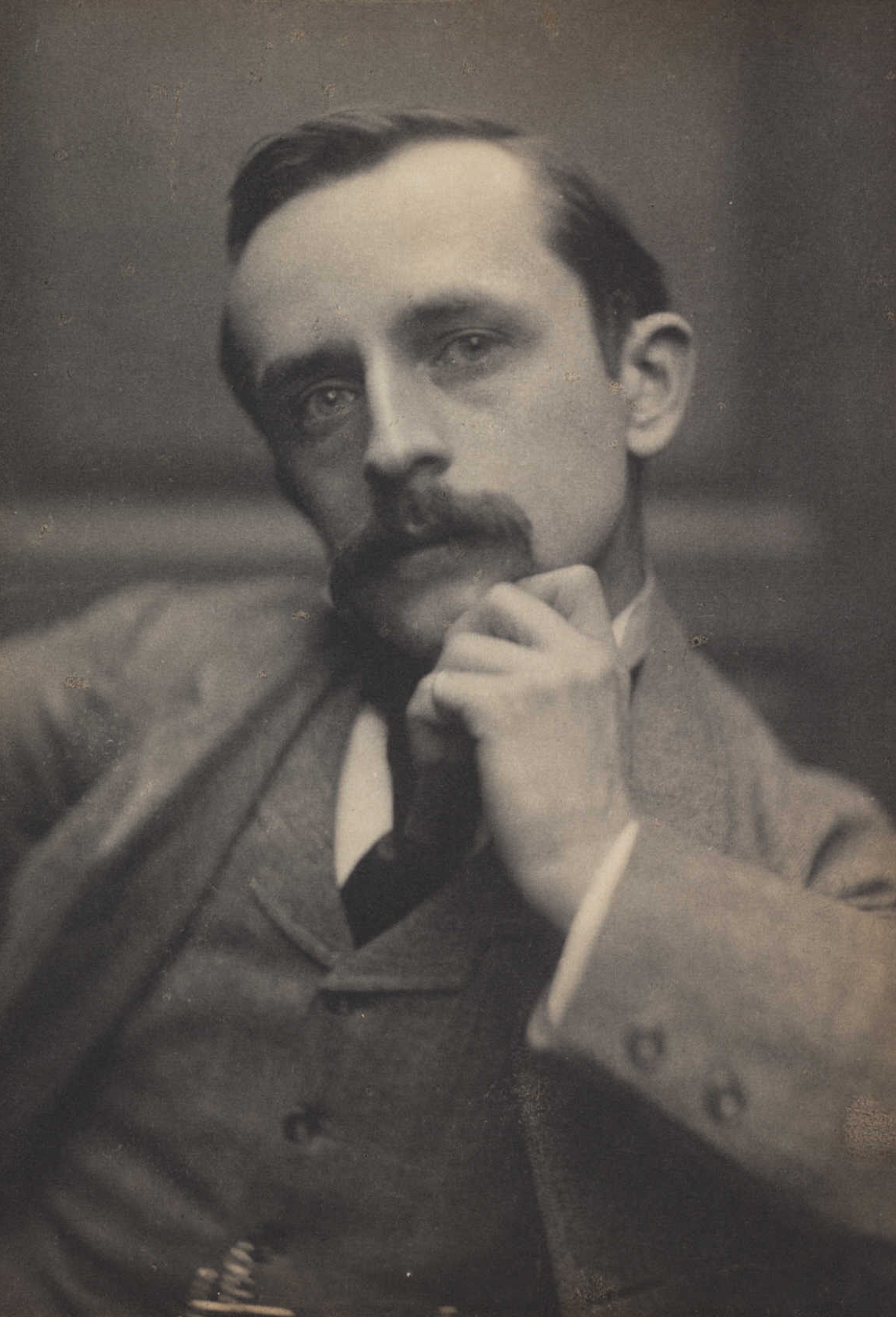

St John Ervine

Ervine had met Shaw through the socialist Fabian Society and had come to regard the playwright as his mentor. Inspired by Shaw, he had started to gain a reputation himself thanks to a series of lively, socially conscious dramas including Mixed Marriage (1911) and in 1913, Jane Clegg.

Despite his socialist leanings Ervine’s comments about his fellow soldiers often come across as snobbish as well as sympathetic. He was better educated than most of those around him, whose “outlook”, he reported was “hopelessly materialistic”, their language “filthy”, “hair-raisingly blasphemous” and “foul in the extreme.” He found it odd that his fellow recruits never read for pleasure, not even newspapers and rarely talked about the war “except to enquire now & then whether it is over.”

“The chief subjects of conversation appear to be food, the sexual functions of women (very coarsely alluded to always)…& the chances of getting leave & there is no discussion about the war at all or about serving King and country. Every man tries to dodge as much as possible. A man who offers to do anything is regarded as a born idiot…. “

By the time he arrived in France in spring 1918, Ervine had achieved a promotion and transfer; he was now a Lieutenant in the 11th Royal Dublin Fusiliers. The war-torn landscape made a deep impression. On patrol in a “quiet part of the line” he told Shaw how struck he was by “the desolation & silence that there is in these parts”, especially at night. “I feel I’m walking through ghosts” he wrote.

Amongst the men around Ervine there had never been any “eagerness to fight” and now, he reported, there was even less:

“I believe that if a vote was taken among the soldiers – old or recruits – on the question of peace, the war would be over before Tuesday. A few soldiers who’ve been to the Front might want the war to continue so that those who haven’t been should get a taste of it, but the rest of these men will be glad when it is over for they’re afraid of being sent back to it…. The very people who seem to want it to go on are the people who will never get within a hundred miles of the Trenches.”

The third act of Ervine’s war began with his being wounded. Moving through the forest of Nieppe on 9 May 1918, he was hit by a shell. Sepsis set in and doctors amputated his leg mid-way between hip and knee. He was shipped back to England and underwent a series of operations in which his “stump” was “reflapped” to make it possible to wear an artificial limb – something he did painfully for the rest of his life.

Like many of those who survived Ervine felt that his life and character had been changed beyond repair by the “four murderous years” of which he had been a part. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s he repeatedly criticized the war’s leaders, their incompetence (as he saw it) and their responsibility for the “lost generation” of young men. When he moved to Devon in the 1920s, he could not bear, he told Shaw, to even pass the time of day with the army of retired colonels who lived roundabout him.

More positively, Ervine began to have considerable success as writer. Always hard-pressed for money, he turned his hand to drawing-room comedies including Mary, Mary Quite Contrary (1923), Anthony and Anna (1925), and most notably The First Mrs. Fraser (1929), a big hit which was turned into a film. His other plays included The Lady of Belmont (1930), Boyd’s Shop (1936), set amongst the lower-middle class of Ervine’s childhood, Robert’s Wife (1938), and Friends and Relations (1941).

Ervine combined playwriting with his job as drama critic for The Observer and The New York World where his sharp-tongued observations made him someone to be frightened of. George Bernard Shaw referred to his friend’s “dragon’s teeth.” Ervine’s willingness to express a controversial opinion meant he was also a frequent radio broadcaster and in demand for public talks.

In his later years Ervine had a reputation for being reactionary and bad-tempered. His 1947 play Private Enterprise takes a pessimistic view of nationalization. But this image, he told friends, was “pure bunk.” It is true that he never recaptured the success of his early plays and despite acclaimed biographies of Bernard Shaw (1956) and Oscar Wilde (1951) he came to seem less relevant. By the time of his death in 1971, he was virtually forgotten by the public

In 2015 the Ulster History Circle unveiled a plaque at Westbourne Presbyterian Church School Belfast where the young John Ervine developed his love of literature and the theatre.

Jane Clegg

First seen at Manchester’s famous Repertory Theatre in April 1913, it will be interesting to see whether the revival of Jane Clegg at the Finborough Theatre will help revive interest in St John Ervine – this very skillful writer and disciple of the much-more celebrated George Bernard Shaw – who wanted to write plays about apparently ordinary people whose lives were more complicated than might be supposed.

In 1913, Jane Clegg, set amongst the suburban lower-middle classes, was highly praised and became one of Ervine’s most successful plays; it was performed in theatres all over the country during the war years and remained part of the British theatre’s repertory well into the 1940s. The play is influenced by Henrick Ibsen’s play of female rebellion A Doll’s House. It also takes the audience into territory being discussed by supporters of votes for women – one of the burning issues of the day in 1913.

In Jane Clegg, a hard-working wife has her loyalty tested when her husband, Henry, a travelling salesman, pockets a cheque meant for the firm he works for. He is also having an affair and has gambling debts. Henry is hardly a desirable husband or father, but Jane is expected to remain with him. Whether she should stay or go is the key question of the play.

Jane Clegg by St John Ervine directed by David Gilmore runs at the Finborough Theatre 23 April -18 May 2019.

https://www.finboroughtheatre.co.uk/productions/2019/jane-clegg.php