By Dr Nick Mansfield & Dr Oliver Wilkinson

Membership Emblem, NFDDSS, c. 1919 (Royal British Legion Collectors Club)

However, while the history of the RBL has gained attention in contemporary historiography, recently in Niall Barr’s as yet unrivalled monograph The Lion and the Poppy (2005), those of the other British veterans’ organisations have received only a smattering of scholarly attention. Indeed, there is at present a striking dearth of material regarding the experiences and activities of ex-service personnel who were demobilised in Britain during and after the war. One-point worth flagging here is that such veteran’s activities need to be understood as a wartime and not solely as a post-war phenomenon. Moreover, the experiences of British veterans have yet to be traced in comparative perspective with the development of veteran’s associations, and ex-service voices, on the continent. Nor should transnational comparison eclipse the need to examine regional difference, together with unifying tendencies, in veteran activities within the UK. It stands to reason, for example, that the context of demobilisation in Ireland from 1916 would present different experiences, challenges and responses than demobilisation in England. Such notions are currently understated and underexplored. Most strikingly of all is an almost total failure to recognise and research the distinct experiences of demobilised ex-servicewomen in Britain; perhaps unsurprising as it is only recent scholarship that has put British women’s’ service experiences onto the historical record.

It is therefore reassuring that some of these issues were probed in January 2015 when Dr Nick Mansfield organised a symposium on ‘Ex-Servicemen After the Great War’ held in conjunction with the ‘Land Fit For Heroes’ exhibition at the People History Museum, Manchester. That event featured some of the leading scholars currently working in the field (including Dr Niall Barr, Dr John Borgonovo, Mr Paul Burnham & Dr David Swift) alongside involvement from the RBL. Yet it served only as a taster, alerting an appetite, identifying omissions in its own schedule (e.g. ex-servicewomen’s experiences were still absent) and providing opportunities to go much further. Now would seem to be the time to do so, not only because of the contemporary relevance of the topic, but also because new sources have come to light which offer avenues for research activities and agendas.

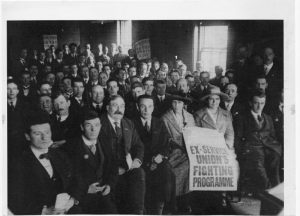

Meeting National Union of Ex-Servicemen, c.1920 (People’s History Museum, Manchester)

The newly discovered Bury St Edmunds Association minutes are the only surviving local archives relating to the early veterans’ organisations. Regretfully they only start on the branch’s formation in September 1919, making it relatively late in the Association’s history and after its radical campaigning heyday. As a result, the Bury St Edmunds Association comes over as relatively conservative; perhaps unsurprising given the background of the area (an agricultural district and a brewing town). In its first meeting, for example, it appointed a Captain R Gibbons as branch auditor, whereas on its foundation the Association refused to admit any officers as members unless they had originally served in the ranks! The Bury St Edmunds branch also accepted, by a narrow vote, a gift of £50 from Lord Invegh, the Guinness magnate, who owned a shooting estate in Suffolk. This indicates a vestige of the Association’s campaigning spirit. So too did its policy of pressing for the proposed Bury St Edmunds’ war memorial to take the form of housing for war widows and disabled veterans rather than a stone memorial. But from early 1920 its efforts appear more mundane; supporting football and cricket teams and by November 1920, establishing its own premises which, significantly, were opened by a senior army officer, General Sir Stuart Ware. Though this association did protest against the overall reduction of war pensions in February 1921, it consistently supported the amalgamation of the three ex-service organisations into the British Legion, with the huge £1.5 million profit from the wartime United Service Fund, as an incentive offered by Lloyd George. It would therefore seem that these records support a view of ex-servicemen’s’ activities which saw original militant local campaigning evolving into relatively conservative activation and approaches.

More nuance and more enquiry is now needed and it is hopeful that both established and emerging academics are turning their attention to this area. Indeed, a symposium will be held next year, 18th March 2017, at the Centre for the Study of Modern Conflict at the University of Edinburgh, designed to explore the experiences of veterans (ex-servicemen and ex-servicewomen) and their dependents during and after the conflict, and to investigate how military service influenced their subsequent lives. This event, which can be followed at what-tommy-did-next.org.uk, has been conceived with British veterans in mind yet it seeks to include transnational perspectives and will feature a keynote by Professor Jay Winter which seeks to explore British experiences through the prism of comparable French developments. Moreover, the event is being organised in tandem with the writing of a new book, edited by Dr David Swift and Dr Oliver Wilkinson, which will synthesis scholarship on ex-servicemen and ex-servicewomen in Britain and Ireland after the First World War. The volume aims to explore some of the currently missing areas in terms of British veterans, fusing a traditional political approach (e.g. examining the how and why ex-service personnel mobilised – or were mobilised – across the political spectrum), with a cultural approach, which will include consideration of gender, disability, identity and memory as connected to the ex-service experience.

As the First World War Centenary continues many are now thinking about the post-2018 landscape and mooting the legacy of their current activities. Yet, for those men and women who served during the First World War their demobilisation did not mark the end of their experiences but simply opened a new phase. Moreover, that phase was defined by the legacies of their war experiences and existed in a political, social, economic and cultural context that was defined by the war. It is an exploration of that legacy and that context that is needed and we hope that the sources, events, publications and issues discussed here will help in that direction.