Summary & Overview

On the 26 & 27 February 2016, IWM North played host to the inaugural event organised by the First World War Postgraduate and Early Career Researchers Network (FWW Network). The conference committee comprised Philippa Read (Chair), Chris Phillips, David Swift and Oliver Wilkinson, with Nick Mansfield acting as a mentor. The group, set up in January 2014 as a self-sustaining off-shoot of IWM North’s Academic Network is dedicated to connecting early stage researchers working on any aspect of the First World War, in order to facilitate new debates, ideas and collaborations relating to the study of the conflict. We further aim to create partnerships between these scholars and organisations, groups, and individuals operating beyond the academy who can offer alternative insights and agendas, opening possibilities for the co-design and co-production of research. Our event, held in the Libeskind Room of IWM North was, therefore, designed to be inclusive.

It combined the latest academic scholarship from established and emerging researchers (30 research papers were delivered in parallel sessions over the two days alongside three keynote addresses by leading scholars in the field), with participation from heritage agencies, libraries, museums, archives, funding bodies, community groups and individual researchers. The academic contributions, which included substantial postgraduate involvement supported by Royal Historical Society bursaries, were augmented by information stands representing important archival repositories (The National Archives), museums (IWM; Leeds Museums & Galleries), organisations (Historic England), funding bodies (The Heritage Lottery Fund; AHRC First World War Engagement Centres), and ongoing commemorative projects (IWM Lives of the First World War).

Meanwhile, the conventions of the traditional academic conference were stretched thanks to performances and displays from creative artists inspired by the First World War. Social media was mobilized both to promote the event and to carry the ideas and debates taking place in Manchester to a wider audience via the network’s Twitter account (@FwwNetwork) and conference hashtag (#fwwcm16). As of 28 March 2016 the network’s Twitter account has 777 followers, is following 1,314, and has made 336 tweets). The five AHRC First World War Engagement Centres, who co-funded the event, were represented throughout the conference and contributed to the discussions and debates that it facilitated. Their participation consisted of papers offered by researchers linked to the various centres and an illuminating roundtable discussion between scholars, community researchers, archives and funding bodies. The conference was almost full to capacity with ninety two participants attending across the two days.

Conference Proceedings

The conference was opened by Philippa Read (University of Leeds), chair of the FWW Network, who introduced the group and the rationale underpinning the event. The parallel panels then began with sessions dedicated to ‘Gender’ and ‘Precedents & Legacies’. In terms of the latter, the first paper was given by Nick Mansfield (University of Central Lancashire/Everyday Lives in the First World War) who has acted as mentor to the FWW Network since its creation. Nick discussed the parallels between different conflicts in his paper ‘Connections between Great Wars, 1642, 1805 and 1914’, particularly in terms of the public perceptions of war and its subsequent mythologisation. On the same panel, Jenny Macleod (University of Hull) analysed the importance of the Gallipoli Centenary for the Turkish, Australian and New Zealand states, and how commemoration of the Gallipoli campaign related to contemporaneous commemoration of the Armenia Genocide. Joel Morley (University of Essex) then discussed the treatment of the First World War by ex-servicemen in inter-war Britain, exploring the transmission of the conflict amongst the generation who would fight in the Second World War. His point about the paradigmatic horror that the conflict represented to later generations would recur throughout the conference. Hence, for example, he related how, due to hearing veterans’ testimonies of the trenches, many Britons in the 1939-45 war were determined to serve anywhere apart from in the infantry where – ironically – they would have been safer, at least before 1944!

On the parallel panel, ‘Gender’, Anna Branach-Kallas (Nicolaus Copernicus University) provided a comparative study of trauma, particularly family trauma, in novels of the Great War that have recently been published in England, France and Canada. She argued that while we usually associate the trauma of war with men at the front, the stress of the conflict transferred to relatives back home. In his paper, Jonathan Black (Kingston University) then argued that the North West of England is particularly rich in examples of more realistic and convincing representations of the British soldier in memorials to the war. In part, claimed Black, this owed something to a pre-existing tradition of memorial sculpture honouring the dead of the area from the second Anglo-Boer War. Black argued that influential images of the British male hero were created before 1914, linking the First World War to earlier conflicts and cultural representations of military masculinity in Britain. The final paper on this panel, by Jack Davies (University of Kent), drew upon the memoirs, newspapers and magazines of wounded soldiers to reveal the forgotten role of women as both disciplinarians and subverts in hospitals. He argued that women within hospitals helped to perpetuate deviant behaviour by aiding soldiers in circumventing military discipline. In addition, Davies claimed, soldiers were able to hide behind their wounds and disabilities to avoid not only military discipline but, to some extent, civilian justice as well.

The latter paper linked neatly to the third panel of the day, dedicated to ‘Disability’, in which Jason Bate (Falmouth University) offered a fascinating insight into the cultural memory of facially injured soldiers. Bate’s research uncovered personal photographs featuring facially injured soldiers taken in the years after the war, often depicting men at leisure or within familial settings, which contrasted sharply with the sterile and distancing photographs taken of their recuperation in hospital. Emily Bartlett (University of Kent) followed, discussing her investigations into the material legacy of charitable provisions for maimed soldiers in the inter-war period, particularly focusing upon the importance of cigarettes to charity in inter-war Britain. Overall, Bartlett claimed, the production, sale, and consumption of cigarettes provided comfort for disabled servicemen in interwar Britain and assisted their transition back to a civilian identity after the war.

In the parallel session, the two papers showcased centenary research projects taking place in the North West, both of which seek to discover new narratives about the impact of the war on communities in the region. Keith Vernon (University of Central Lancashire) outlined an ongoing project which is using the registers of the Harris Institute (the forerunner of the University of Central Lancashire) to explore the wartime experiences of non-combatants, especially women and adolescents, in Preston during the First World War. Partnering with ‘Preston Remembers’ (a Heritage Lottery Fund partnership project), the project aims to use the community research already conducted into the city’s war memorials, layering the wartime data of the Harris Registers, in an attempt to relate the wartime experiences of those non-combatants to the combatant experiences of the soldiers who have subsequently been recorded on community war memorials. The sophistication that such methods can achieve were indicated by the second paper, jointly delivered by Ian Gregory and Corinna Peniston-Bird (both of Lancaster University). Gregory and Bird discussed the Streets of Mourning Project, focused on the city of Lancaster. Here, digital humanities have been effectively used to map First World War casualties across the city, prompting an innovative investigation into the spatial dimensions of loss on the home front. The resulting data and maps, representing casualty densities, allows for considerable further investigation into questions such as patterns of habitation and enlistment, and familial patterns of recruitment during the war. Most powerfully, however, the project allows the deaths to be related to the communities affected.

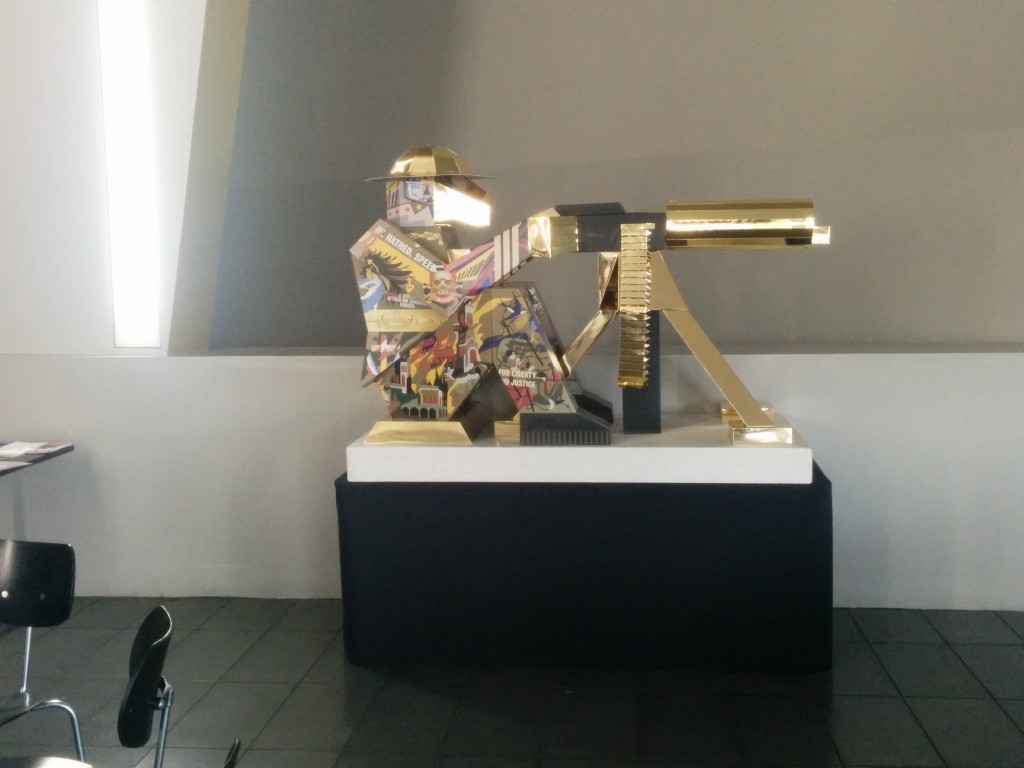

At lunchtime, delegates moved through the museum’s main gallery space to the Watershard Café where an impressive sculpture entitled ‘BLAST’ had been set up by Ian Kirkpatrick, an independent artist, and Lucy Moore, curator at Leeds Museum and Galleries. The sculpture was one of a series created by Kirkpatrick during his residency with Leeds Museums and Galleries. It depicted a British machine gunner, and was partly inspired by the goss china ornaments produced during the war. The art work adorning the figure was taken from war artefacts held in Leeds Museum’s collections. Kirkpatrick and Moore gave a brief overview of the sculpture and the ‘A Graphic War’ exhibition trail, which had explored the role of graphic design at home and on the front lines during the First World War, within which ‘BLAST’ had featured. Delegates were then able to peruse the sculpture and discuss the piece further with the artist. The sculpture remained on display in the Watershard Café during the full two days of the conference, and was thus viewed by public visitors to the museum as well as conference delegates.

The afternoon sessions began with parallel panels. In ‘Material Cultures’, Sonya Andrew (University of Manchester) began by discussing the development of two textile triptychs that were created to form visual narratives on the imprisonment of a conscientious objector in the First World War, and the impact of these on the CO’s family. Andrew examined the processes of recalling and commemorating conscientious objection, and the construction of visual narrative as an act of individual remembrance, from the perspective of the maker as author. She contrasted this with audience interpretations of the textiles when located in a range of buildings, such as church, gallery, bank and museum. Andrew’s presentation concluded by examining the impact of site on interpretations of the visual narrative, considering how the function of a building may contribute to shaping viewers’ perceptions of the images in the textiles. Hanna Smyth (University of Oxford) then analysed the Canadian and South African war memorials at Vimy and Delville Wood, and considered what they can reveal about the identities of the nations whose dead they honoured. For the Canadians, the memorial embodied the fusion of British and French identities; for the South Africans, of British and Afrikaner. However, neither memorial paid tribute to the indigenous peoples of either country.

Meanwhile, in ‘Forgotten Episodes’, Florence Largillière (Queen Mary University, London) explored French Jewish veterans of the First World War, examining the role of the conflict in perceptions and practices of antisemitism in the 1930s. Veterans felt they had proved their worth during the war. They had fought and many had died for France. They believed that they deserved to be treated as valued members of the French nation. Amidst growing antisemitism in 1930s Europe, French Jewish veterans reacted by reminding the nation of their participation in the Great War via overt displays of their patriotism. However, their efforts would not protect patriotic Jews from the 1940 Antisemitic Statute. French Jewish veterans became second-class citizens under the Vichy regime, despite their heroic accomplishments, their nationalist discourses, their medals, even their Legions of Honour. In the second paper of the session, Christophe Declercq (University College, London) gave an insight into the disappearance of the history of Belgian refugees in Britain during and after the First World War. One reason for the ‘forgetting’ of this mass migration of peoples was the mobility and transnational character of the Belgian exile, which Declercq related to Belgians disappearing from view to the current commemorative community projects.

The first day concluded with a keynote by Helen McCartney (King’s College, London) which examined whether the familiar narratives of the First World War have been challenged or reinforced by new commemorative projects. Through an analysis of two projects, the Tower of London poppy installation and the letter to the Unknown Soldier website and book, McCartney sought to establish how a variety of different local and national interest groups had interacted with commemorative projects. She argued that, alongside the dominant ‘futility script’ attached to commemorations of the conflict, there also exists an opposing ‘sacrificial narrative’ that stresses the debt owed to the fallen for our ongoing ‘freedom’. McCartney’s paper provided a hugely engaging, and very fitting keynote upon which to end the first day of the conference, and it attracted considerable further discussion in the question time that followed. As day one closed, it emphasised questions that resonated throughout the conference: Why should the First World War be remembered? Why is the centenary such an important moment? And, crucially, how should we remember the First World War?

Day two began with a powerful and thought provoking keynote address. Jay Winter (Yale University), delivered a paper which dealt with the conference’s key themes through a combination of humour, personal reflection, and a survey of the speaker’s long and distinguished career as a historian of the conflict. Winter raised questions relevant to practitioners of History in general, as well as those particularly concerned with the First World War. He began with the assertion that there is a tendency to revert to national narratives, based on national identities, in the research and remembrance of the First World War. He went on to trace key developments in the historiographical approaches to the conflict which led to the creation of transnational histories which, though challenging national identities and narratives, had major impacts in the way the war is remembered and commemorated. Indeed, Winter claimed that transnational history was local history, and that the transnational perspective he presented provided a better way to write national histories. He linked these developments to his experiences as an adviser at the Historial de la Grande Guerre, Peronne, allowing him to further examine the expansion of public history which has radically changed the landscape in which history is understood. Indeed, Winter stressed the compatibility of such public histories with academic scholarship, asserting the responsibilities that he feels academics have in the sphere of public history. Academic historians, he claimed, have a responsibility to ‘do’ public history or others will ‘do it worse!’ Winter’s paper both illuminated the first day’s discussions and ignited debates which continued throughout the second day.

Following the keynote, proceedings then moved to the day’s first set of parallel panels. Santanu Das (King’s College, London) began discussions in the ‘Global Perspectives’ panel by examining the importance of race, ethnicity and religion in commemorations in Britain, India, Pakistan and elsewhere. On a similar vein, Richard Smith (Goldsmith’s, London) discussed the memory and representation of West Indian servicemen fighting for Britain during the conflict. Therein, he situated these memories within recent media representations, especially those on the BBC, over the course of the war’s centenary. Representations of war experiences similarly characterised Burcin Cakir’s (Glasgow Caledonian University) paper as she spoke about the place of Gallipoli in Turkish literature and memorabilia, and the enduring significance of the landings for the Turkish regime today.

‘Faith’ constituted the theme of the parallel session, which began with Arabella Hobbs (University of Pennsylvania) seeking to place France’s attempts to come to terms with the war within the context of the nation’s relationship with the Catholic church. By examining post-war representations of the gueule cassée, Hobbs showed how Catholicism positioned itself as an indispensable force for healing in post-war France. Gethin Matthews (Swansea University) also focused on Christianity, within the context of Welsh non-conformity and the form and function of war memorials erected in Welsh chapels. Matthews’ paper drew heavily upon the speaker’s wide ranging research, and delegates were treated to a huge number of photographs, many from Matthews’ own collection, of the various memorials erected to Wales’ fallen. Catriona McCartney (University of Durham) drew the session to a close by examining the role of British Sunday Schools in the First World War. As bastions of Christianity in Britain both before and during the war, McCartney considered the role of the Sunday School on the home front, the impact of the war on the schools and, linking to the two previous papers in the panel, discussed how particular religious communities attempted to commemorate ‘their’ fallen in the war’s aftermath.

The days second set of parallel panels saw Geoff Cubitt (University of York) and Jessica Moody (University of Portsmouth) opening the ‘Cultural Representations’ panel by discussing their research into visitor experiences to First World War exhibitions at York Castle Museum and Scarborough Art Gallery. In the paper, Cubitt and Moody offered insights into the meanings attached to commemorative activities by members of the public, alongside highlighting some of the more amusing incidence of ignorance found among those who viewed the exhibitions. Their paper was followed by Suzie Hanna and Alisa Miller (Norwich University of the Arts) who discussed their novel work on an animated tribute to the ex-servicemen of the Great War. Hanna and Miller focused on remembering men who had survived the war, and illuminated challenges they faced in the post-war civilian landscape which seemed odd and alien to them following their war experiences. Their film, clips from which were played alongside discussions of the animation processes, thus raised important questions regarding the legacy of the conflict throughout the twentieth century.

The parallel session consisted of a roundtable discussion chaired by Alison Fell (University of Leeds) representing the Gateways to the AHRC First World War Engagement Centre. Participants also included Keith Lilley (Queen’s University, Belfast) representing the Living Legacies AHRC First World War Engagement Centre, Michael Noble (University of Nottingham) representing the Hidden Histories AHRC First World War Enjoyment Centre, Karen Brookfield representing the Heritage Lottery Fund, Rosemary Collins (Open University) speaking in relation to a centenary community project, and Liz Woolley as an independent researcher. Therein, the representatives of the AHRC First World War Engagement Centres provided an overview of the role of the centres, and the nature of their activities to date in support of First World War projects. Fell noted how her roles within the centre pushed her beyond her traditional ‘comfort zones’ via involvement in diverse projects and, as a consequence, had provided new directions and new insights for her own work. Lilley and Noble, meanwhile, stressed how the centres sought to begin with the community project, addressing the fundamental question of ‘What do community research projects want/need from academics?’ Here, answers could include access to the skills or specialisms or, equally, it might be simply that the centre can facilitate access to university resources or tools necessary to deliver a community project. Brookfield provided further information about the role of the Heritage Lottery Fund within the centres, as well as the other schemes through which organisations are able to support First World War community research. Collins provided an overview of a specific project, supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, which has explored the impact of the war on Radcliffe-on-Trent. Her contribution stressed the community role of such projects; arguing that they were not solely about uncovering the past but that they also served a contemporary social function, cohering communities in pursuit of ‘their’ histories. Woolley was able to give a further example of a community history project, the commemoration of the 66 men named on the war memorial in St Matthew’s Church in Grandpont, south Oxford, which provides a model of how other local communities could carry out similar projects. Along with the diverse experiences and insights offered by the panel members, the session afforded considerable time for discussion and questions. Once the floor was opened there were frank discussions between the various agencies and individuals represented at the event. Academic contributors, for example, spoke of the challenges and benefits of co-produced research; archives were able to provide insight into their activities, especially their community/public engagement agendas; independent scholars further illuminated the challenges, indeed the intimidation, that they encountered in undertaking First World War research.

Lunch was again held in the Watershard café, accessed through the main gallery space. However, early return to the Liberskind room afforded delegates the opportunity to view the conference’s second artistic offering. Dawn Cole introduced and then performed a dramatic piece entitled ‘The Silence of Knitting’. The performance was developed in response to the silence that is perceived during war, and was based on the archive of VAD Nurse Clarice Spratling. The knitting itself proved powerful, silencing the delegates (fortunately for the only time over the two days!).

After lunch, the final keynote paper of the conference was delivered by Maggie Andrews (University of Worcester). Andrews’ paper discussed the role of gender and the home front in the commemorations linked with the centenary, drawing upon her wide ranging experience of commemorative practices as part of the Voices of War and Peace AHRC First World War Engagement Centre. She noted that we tend to remember soldiers, particularly the fallen, through the lens of their domestic role: as husbands, fathers, and sons, rather than as armed and trained soldiers. This exposed how the domestic could be mobilised to make the battlefront more palatable. Andrews further engaged with fundamental questions about the impact of the present on interpretations of the past, exploring the multiple and malleable meanings about the war found in current commemorative activities. She provided a keynote which asked as many questions as it answered, and one which prompted much discussion both immediately after and for the rest of the conference, her ideas and evidence meshing well with the other keynote addresses.

Following Professor Andrews’ paper, the conference reverted back to parallel sessions. In ‘Commonwealth Commemorations’, Penny Edwell (Australian Defence Force Academy) provided a run-down of individual and community-based commemorative projects taking place in Australia, and considered the manner in which Australian national identities were being both challenged and confirmed by the commemoration. Her paper was followed by Teresa Iacobelli (Queen’s University, Kingston), whose paper focused on the significance of popular media and commemorations in determining evolving narratives of the war in Canada. The two papers covered similar ground and complemented one another, with multiple questions arising with relevance to both speakers.

In the parallel session, ‘Transmitted Legacies’, Jessica Hammett (University of Sussex) explored the role of small groups in remembering the First World War. Her paper investigated how First World War veterans mobilised an ex-service identity, based on their experiences in that conflict, whilst employed within civil defence during the Second World War. Interestingly, Hammett examined how the First World War was mobilised by these men in response to criticism directed at members of the civil defence during the Second World War. Here, her work related to other groups of ex-servicemen who sought to mobilise their First World War experiences to deal with post-war challenges, such as the French Jewish veterans as considered by Florence Largillière on day one. Vincent Trott (Open University) then offered his insights into the importance of interwar literature in forging memories of the war for men too young to have taken part. Exploring the authorial intent and reception of such literature, especially during the so-called war books boom of 1928-30, Trott contextualised the role of literature in imbuing the new generation with dominant ideas about war and about manhood which, ultimately, would impact on their experiences during the Second World War.

The final parallel sessions dealt with ‘Sites of Memory’ and ‘Uncomfortable Pasts’. In the former, Laura Brandon of the Canadian War Museum spoke of the recent controversy surrounding Canada’s ‘Never Forgotten’ National Memorial, while Emma Login (National Memorial Arboretum) provided an overview of changing attitudes to memorialisation in Peterborough over the one hundred years between 1914 and 2014. Both stressed the ongoing relevance of memorialising the First World War, and discussed the competing agendas and interests involved in these processes from the perspectives of Canadian and British ‘stakeholders’. ‘Uncomfortable Pasts’ began with a joint paper, by Matthias Meirlaen (Université Lille) and Karla Vanraepenbusch (Université Catholique de Louvain) on execution sites in occupied Belgium and France. They revealed the use of execution sites in France and Belgium after the war, and the methods by which civil authorities commemorated the memories of the executed, both on the sites themselves and in the cities of Antwerp, Liege and Lille. Emile Coetzee (North West University) continued the theme of commemoration, this time of a far less celebratory nature. Coetzee’s paper discussed the intriguing case of Wijand ‘Vic’ Hamman, an Afrikaner solider killed in the war, who was subsequently ignored by his home town. Coetzee’s paper illuminated the depth of feeling among the community of Lichtenburg towards the British, the residue of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 and the ongoing controversies of South African politics. Finally, Kamil Ruszala (Jagiellonian University) presented the final paper of the conference, and the only one to focus exclusively upon the Eastern Front. Ruszala discussed the work of the Austro-Hungarian Army in creating the ‘warrior cemeteries’ of the Gorlice-Tarnów battlefield. Drawing upon a range of architectural drawings of both realised and unrealised creations, Ruszala highlighted the use of heroic, mythological imagery in the cemeteries of the Austro-Hungarian armies, and emphasised the role of famous artists, sculptors and painters within the Kriegsgräberabteilung Krakau.

Following the papers, Oliver Wilkinson and Philippa Read brought the conference to a formal close by thanking all of the participants for a highly engaging, interesting and (we hoped) an enjoyable event. The organising committee is currently discussing routes to further disseminate the research findings and collaborations facilitated by the conference. Moreover, the FWW Network remains an active forum for early career and postgraduate research into the First World War. It intends to establish and maintain contact with researchers in these stages of their career, and to organise future events for both academic and wider audiences. On behalf of the network, and all those who participated or attended, our thanks are reiterated to the AHRC First World War Engagement Centres and the Royal Historical Society for their generous financial support which made the event possible.