Centre member Jim Beach (University of Northampton) provides a retrospective of the ‘The End of the War & the Reshaping of a Century’ that took place in Early September.

One symptom of a good conference is that you find yourself struggling to decide which parallel session to attend. It’s a good problem to have and it plagued me throughout the recent conference entitled 1918-2018: The End of the War & The Reshaping of a Century.

At one point I had to decide between the demilitarisation of the Belgian capital in 1918 or a British Army vegetable show in the same year. Was it to be Brussels or Brussels Sprouts?

Hosted by the University of Wolverhampton, the conference included six keynote lectures, sixty shorter papers, an after-dinner address, a round-table discussion, and the launch of digital exhibition. The latter, entitled ‘Aftermath’, was focused on the social, economic, health and political issues affecting veterans.

The conference sponsors included the Royal Historical Society, the Western Front Association (WFA), the First World War Network, and the five AHRC-funded engagement centres.

Unsurprisingly given this support base, attendees came from a broad spectrum; WFA members, a variety of students, plus academics at all career stages and from around the world. Probably because of this mixture, the event was noticeably informal in tone and the Q&A sessions were some of the best I’ve witnessed.

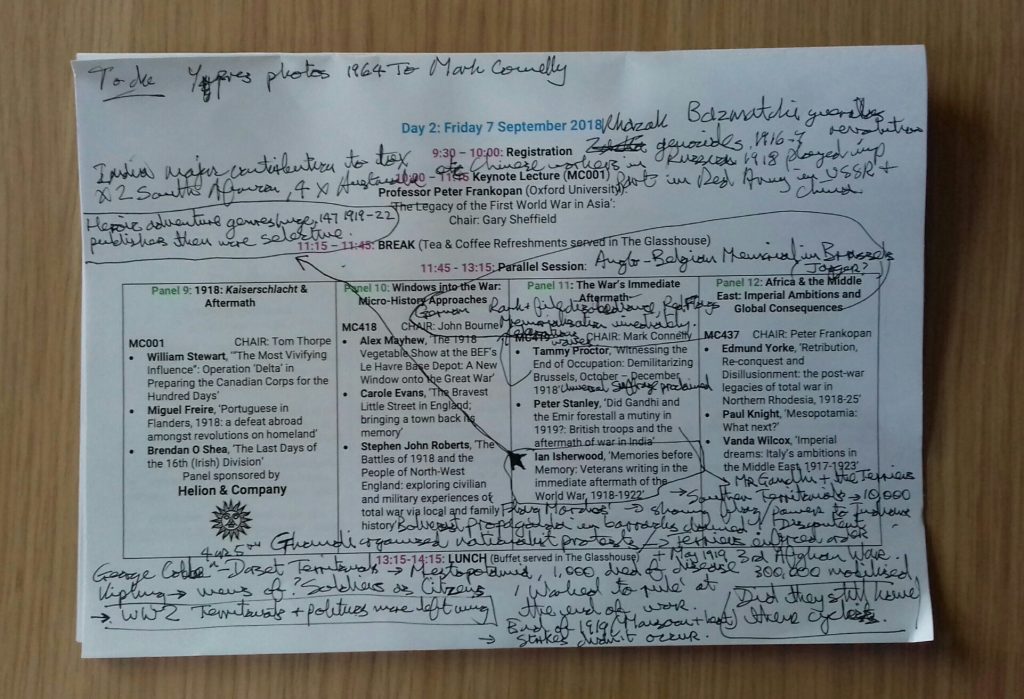

On the second day I was joined by Nick Mansfield, also from Everyday Lives in War. He made copious notes on Panel 11 and, as you can see, I captured them for posterity.

And Panel 11 itself was a good example of the diversity of the conference content. Tammy Proctor unpacked the uneasy transition from war to peace in Belgium; Peter Stanley offered the hitherto untold story of the Territorials who served in India; while Ian Isherwood showed how the publishing industry shaped the stories told in the immediate aftermath of war.

Of the keynotes, Laura Ugolini’s exploration of masculinity was especially interesting. I also found Alison Fell’s examination of women veterans very thought-provoking and it has certainly prompted me to reconsider the canon of interwar intelligence memoirs.

The conference was bookended by lectures from two world-renowned scholars of the conflict. John Horne began by challenging the American/Western European notion that the war ended on 11 November 1918. Then, at the end of proceedings, Jay Winter suggested that there were, in fact, two overlapping wars; the well-known one that ran from 1914 to 1918 plus another, far more brutal, conflict that began in 1917 and ended in 1923.

This should perhaps give us pause for thought. In Britain we have just come to the end of a conflict commemoration process that has, generally, been disconnected from the rough and tumble of contemporary politics. Across East/Central Europe and the wider world, the centenaries between 2019 and 2023 will almost certainly be more contested. And yet, in many instances, the British were deeply involved in those events. How might we mark them?