‘German and British descendants share heritage from the Great War’ is a collaborative project to record and share family memories of the First World War. Led by London’s reminiscence organisation Age Exchange, who will work alongside Rachel Duffett and Mike Roper from the Hertfordshire Engagement Centre, the project compares the war’s impact on family histories in each country, from the inter-war years through to the present and the participants’ experiences of remembrance and commemoration today. British and German elders will record and then share their First World War family histories at a four day event in April 2016. The exchange will be filmed and family archive material will be digitised. A film documentary sharing the story of the project will be screened at media, heritage and community venues in London from July 2016, and made available on-line. Materials from the exchange will also be used to create Smart Phone learning materials for schools. Students will share their resulting learning and interpretation at ‘Meeting in No Man’s Land’ Open Days. All recorded and digitised material from the project will go on-line and the project archive will be given to the First World War Engagement Centre (Herts) to support future research.

Age Exchange, the lead partner in the project, has established contacts with German partners and has obtained HLF funding. Duffett and Roper will help to refine the approach to the interviews and collection of family heritage, and their knowledge of the interwar legacies in each country will provide a broader context for the stories that emerge. They will benefit from the collaboration with German experts in intergenerational therapies, and the experience of comparative research will sharpen their understanding of what is distinctive about British family legacies of the conflict.

The project gives us a unique opportunity to reflect on WW1 heritage making in the centenary. Age Exchange is a world-leader in reminiscence activities, with a long history of community-led oral history activities which seek to challenge and transform understandings of history. We will observe ‘live’ what a community organisation like Age Exchange contributes to contemporary debates about the memory of the First World War, and assess the changes in understandings and historical consciousness it sets in train. We will keep a blog throughout recording our impressions, which will be posted on the Herts Centre website. Watch this space!

Mike Roper

Contributed by Rachel Duffett

The experience in Rosenheim was overwhelming. As a First World War historian, I’ve read so many affecting accounts written by participants and their families. I know what it feels like to be deeply moved by the hopeful but anxious diaries that end abruptly on 30 June 1916 or the letters that struggle to encapsulate the love families desperately wanted men in the trenches to feel. But, I’ve never felt anything quite like I did in a room in 5 Pettenkoferstrasse for an hour on Sunday afternoon when the children of two veterans sat together and shared their family legacies.

Emotion and history are tricky bedfellows. We’re trained from our earliest years to seek objectivity, to focus on the facts and the responses of the subjects where it’s permissible to appraise emotions intellectually, but our own feelings are not part of that academic equation. As I write this, I can accept its importance in the creation of history, but it doesn’t prevent me from wanting to convey a sense of how it felt to be in that room. Why is that? It’s not about seeking cathartic therapeutic relief, although my psychoanalytically informed colleagues might argue otherwise and perhaps they’d be right, at least subconsciously, but it feels more as if I witnessed something of immense value that needs to be shared. I fear I’m not going to come out of this well, whether in terms of suspected psychological disturbance or possible semi-religious mania, but such was the power of this ‘meeting in no man’s land’, I don’t care.

[metaslider id=1500]

The elders’ fathers had, in 1917, faced each other at Ypres and now their daughters – with a combined age of almost 170 years – sat side-by-side in Bavaria, the past and present together. The British elder spoke of the loss of her father twelve years after the war when she was four, of the invalid that he’d become as a result of gassing and her memories of him as a slipper-clad patient. That image fell away when she read one of the love letters that he’d sent her mother from the Western Front, here was a vital and passionate young man, longing to be with his fiancée and looking forward to a life together far away from the dreadfulness of war. Written by a young man and read by an elderly woman almost a century later, there was a continuity that bridged time and space: the circle of author and recipient was completed in the reader, their daughter. Another circle seemed to be completed in the attentiveness of the German elder, whose concern and sensitivity constructed a very different national relationship one hundred years on. Her father had returned from the war intact, although his exaggerated sense of order and energetic disciplining of his children spoke of a domestic life which had been shaped by the military experience of his youth. She had brought with her an extensive collection of postcards he’d sent to his parents from Belgium and France where the destruction of war featured frequently in the images. Scenes of broken churches and rubble-piled streets provided the medium for communication with home, for requests for winter underwear and descriptions of Sunday dinners – ‘soup, roast meat and green salad’ – surely the epitome of mixed messages?

The women shared their pasts, held fragments of each other’s family stories and talked about not just their fathers’ war experiences, but how the war had seeped into their own lives through their paternal relationships – or absence of them. There was humour, the German elder showed her father’s service record book which listed his scores at the rifle range – very low! – and said that his British opponent was probably lucky to be opposite such a poor shot. But most of all there was love, expressed as a deep desire to understand each other’s lives, to look together at not just a divided past but to a united future. All the clichés about ‘we must understand the past or be condemned to repeat it’ fell away and the sentiment achieved true meaning in that room with those two women. I’m so grateful that I was able to witness it, it was the highpoint of a project that had so many.

Contributed by Mike Roper

I’m just back from our Meeting. It was an incredibly intense experience and I have to say that for much of the time, because of the differences in language, the sense of responsibility for aged participants, the feeling of being on the edge that observation entails, and the total immersion that Age Exchange’s reminiscence approach entails, I was completely out of my comfort zone.

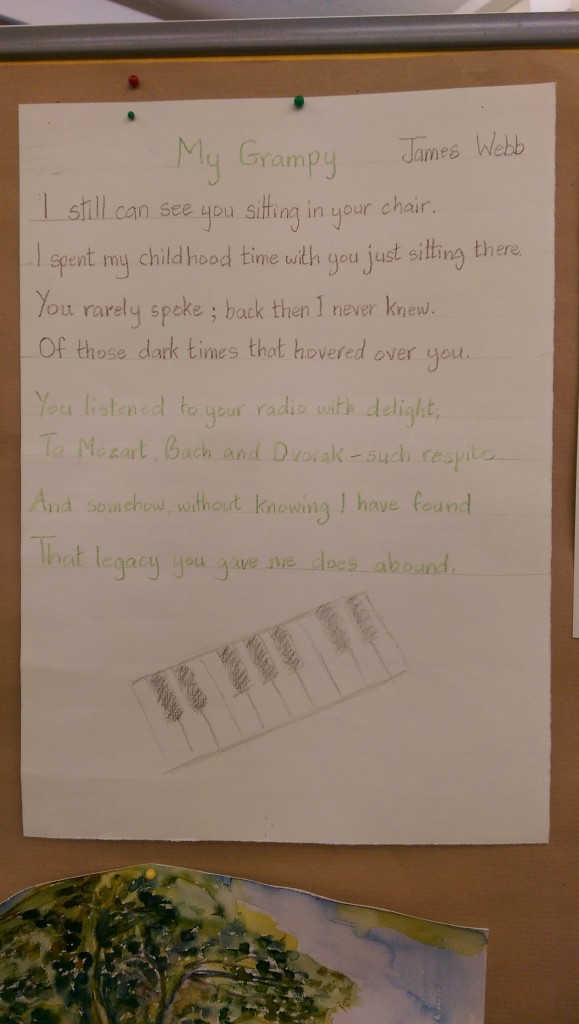

Poem to a Grandfather who never spoke about the War but whose story her granddaughter now knows. (Click to Enlarge)

What emerged, however, was a novel kind of emotional history, which drew on all our senses and gripped participants and organisers alike. Having spent years reading wartime letters for my book The Secret Battle, I sometimes feel I’ve become inured to their contents. Yet on many occasions during the four days I had a strong sense of being transported back in time. One of our translators broke down at the end of the penultimate day as a British elder read out her family’s letters to a German elder, written in 1914. Her grandparents had married shortly before her grandfather left for war, and her grandmother’s letters were about preparing the home to which he would return, hinting at her concerns about temptations he might encounter, and promising to make him happy when she returned. Her passion was palpable. What had moved the translator was her recognition of what people were feeling in 1914, coupled with her knowledge of how the war would develop, and the destruction it would wreak.

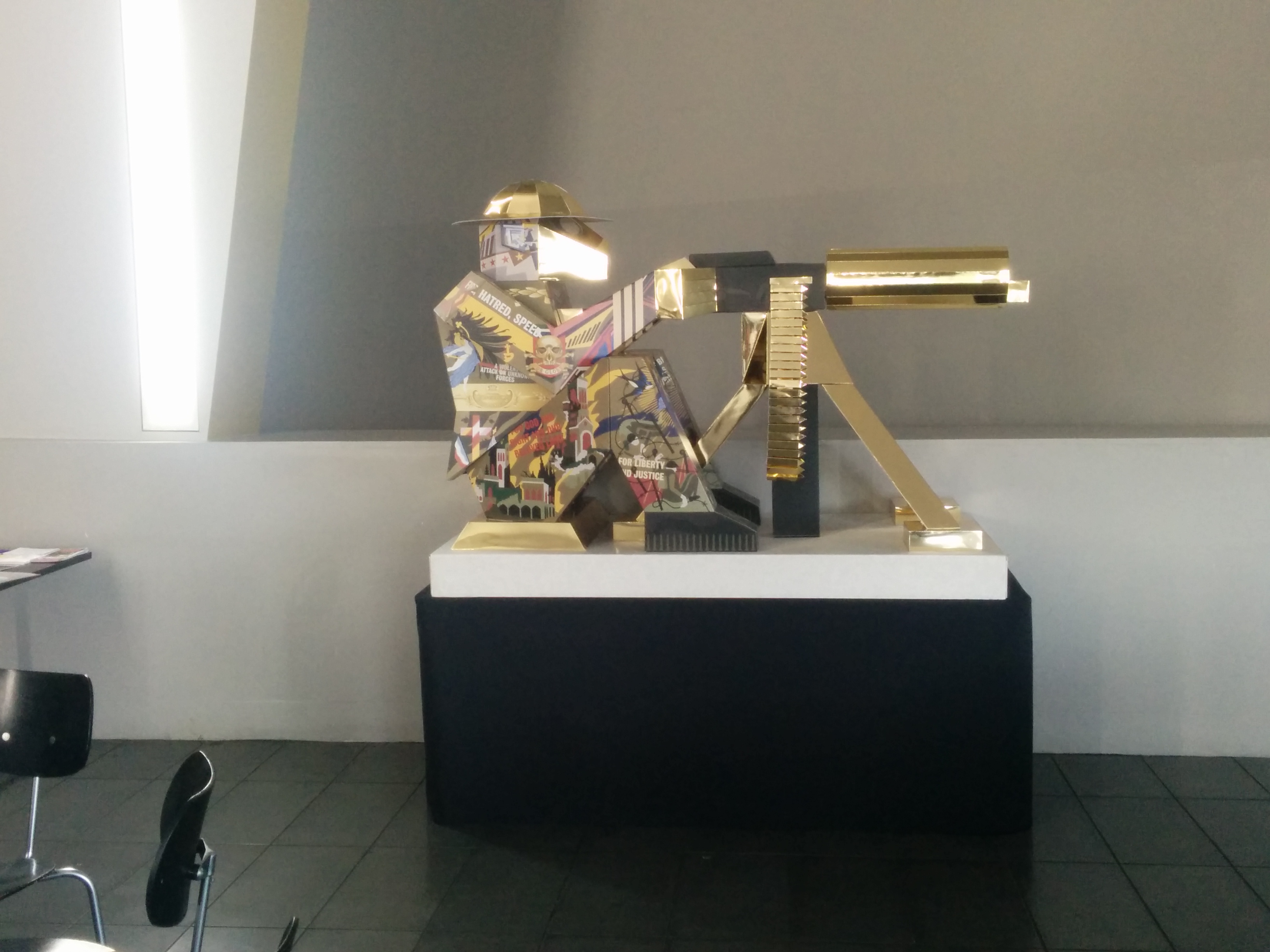

Part of what made this a powerful experience was the way the different activities engaged us. The sequence of events put people at ease, and allowed them to get to know each other and reveal their histories little by little. After the individual interviews with the 12 British and German participants, Day 2 began with a symbolic Meeting in No Man’s Land, where the two parties lined up on either side of the room, stepping forward one by one to present and introduce a family object about to war to their opposite number. In the afternoon, they each produced a work of art about their story. For some the legacy was in the art itself: a German participant whose artist father and mother had split up when she was little and who mourned the loss of contact with her father, painted her father’s favourite place in the Austrian alps. Her own ability as an artist was clear to everyone. Day 3 began with lectures by me and the psychologist Jurgen Müller-Hohagen on the legacies of WW1 in each country, the idea being to help place individual stories in a larger context, historical and psychological. The participants were then paired off and invited to show each other their artefacts and talk to each other about the war’s legacies in their family. This revealed new aspects of the stories that had been told in the separate interviews, and encouraged people to think afresh about their histories. Sometimes the experience was uncomfortable. The anger of a German elder about the taking away of her father’s shop by the British during denazification after the Second War was palpable. A British participant read out extracts in which her great uncle railed against German imperialism, proclaimed ‘the cause as a righteous one’, and the British Army as ‘second to none’. Her German partner listened intently, then responded by saying that perhaps the Kaiser had been a war monger, but ‘these differences are past.’

[metaslider id=1505]

For the Germans it seemed to me that the First World war is only just emerging from the Second. Their stories are not as tried and tested as the British ones – there was a fascinating sense of movement across the four days, as participants went home and discovered further information from relatives, or undertook new research. A German participant who I interviewed about his paternal grandfather came back the following day with a new story, about his maternal grandfather who was a disabled veteran. On Day 2 a trip was organised to Rosenheim’s War Memorial, but not all the German participants knew where it was. One of the organisers had done research on the Memorial for the purpose of our visit. She explained that she had never felt comfortable about formal commemorations as they were too freighted with the legacies of National Socialism. On our last day, however, she declared her intent to spread a ‘virus’, encouraging others to research their family histories of the First World War. Perhaps the most poignant expression of this shift in historical consciousness came from the artist in our organising group whose grandfather had been a member of the SA. She had been involved in radical movements throughout her life, and had hated everything her grandfather stood for. Having taken part in the Meeting, she explained, she could now see her grandfather not only as the Nazi he became, but as a young man enduring a war of terrible destruction.

Follow Age Exchange on Twitter @NoMansLand2016

Related Articles:

Reports from Meeting in No Man’s Land, Rosenheim – April 8th – By Rachel Duffett and Mike Roper

Meeting in No Man’s Land – Interviews with British elders, Blackheath, March 22nd-23rd – By Rachel Duffett and Mike Roper

Meeting in No Man’s Land – Planning Meeting, Rosenheim, January 2016 – By Rachel Duffett and Mike Roper